Authored by Aaron Hertzberg via The Brownstone Institute,

First-person report of QR Codes, Digital IDs, and police militarization of Paris

This is a guest post from a friend who is on the ground in Paris reporting what the situation is like.

The best way to begin might be to say that there are three distinct categories of Olympic games sites that the City of Paris wants to make ultra-safe for visitors and athletes, each with its own unique security challenges.

First, there are the many official, already-existing sporting venues (stadiums, arenas, tennis courts, aquatic centers, etc.) located throughout Paris and France. These require the least amount of novel security measures, whether in the form of protective perimeters or the (unusual) methods used to maintain them.

Included among these is the historic Grand Palais, an architectural jewel from 1900 located at the foot of the Champs-Elysées. A monumentally massive building with a marvelously versatile interior space, it regularly plays host to museum exhibitions of all types, in addition to galas, elaborate fashion shows, concerts, conventions, and even an ice-skating rink. Turning it into an Olympic sporting event site wouldn’t have been very difficult.

Second, and complementing these dedicated sporting facilities, are several famous outdoor public monuments and historic landmarks that have been transformed into temporary games sites.

These comprise, most notably, the Trocadero and the area next to the Eiffel Tower, the Château de Versailles, the Place de la Concorde, the Alexandre III Bridge, and the expansive lawns in front of the Hôtel des Invalides.

Massive amounts of bleachers and facilities for ticketed spectators have been brought in and creatively set up to adapt to the often unusual contours and spatial constraints of these areas. Seeing the obelisk at la Place de la Concorde hidden behind a patchwork of crisscrossing bars and stands was strange indeed. From the outside, the expansive fenced-in area, with giant stands rising out from the emptied-out streets, looks like a curious sort of fairground.

Third, and arguably most importantly, there is the Seine River itself, which will be the location of the opening ceremony as well as several aquatic competitions.

From a security standpoint, the first category of venues is the most straightforward because entrances and exits are already part of the structures. All that is necessary to guarantee spectator and athlete safety is to set up slightly expanded perimeters around the buildings and flood the access points with staff and security guards so that no one – or anything – dangerous gets through.

Think of the Barclays Center on game night. Plenty of space to accommodate the crowds at the entrance waiting to go through security, with minimal disruptions to the immediate surroundings.

The second category of event sites, as mentioned above, significantly modify public spaces outdoors; they pose greater security and logistical challenges, as the physical enclosures separating “outside from inside” – separating the ticketed spectators from the unticketed – have to be brought in on trucks and set up.

These barriers are made up of hundreds of miles of what are essentially chain link fence units (about 10 feet long and 7 feet high) set into concrete slabs that can be moved around and connected as needed.

They wrap around the temporary outdoor sporting event sites in odd, unsightly ways and, notwithstanding the considerable effort to line them up neatly, look to many like human kennels. (Upset Parisians are referring to them as cages.)

The last site/category of Olympic events, and the location of the opening ceremony, the Seine River, is the most problematic in terms of security perimeters.

In fact, in order to meet the endless safety, commercial, and sanitary needs associated with the many uses to which the river is being put, an unprecedented thing has taken place: for 8 days leading up to the opening ceremony (tomorrow), the Seine and its immediate surroundings have undergone a form of privatization that has kept almost the entirety of the Parisian population off its riverbanks and away from its nearest surrounding streets and bridges.

Implementing this shutting down of the river has involved widespread use of the aforementioned chainlink-type moveable fences – thousands of them – along with a novel but not entirely unfamiliar technological device: the QR-coded pass.

To help explain what this is looking like on the ground, I’ll attempt to draw a hypothetical analogy with NYC.

It’s a highly flawed comparison due to the very different layout and features of the two cities, with the proportions off, but it’s the best I could come up with under pressure to illustrate the point.

Imagine that 42nd Street in NYC was the Seine River, and that all of the Avenues slicing through it were Paris’ many bridges connecting the North and South sides of the city.

Now picture the sidewalks of 42nd Street as Paris’ Right and Left banks, or riversides, and all the buildings on the North and South sides of 42nd Street, extending down its entire length, like the rows of charming old Parisian apartment buildings you see overlooking the Seine in postcards.

Okay, now think of what life would be like in Manhattan if, for 8 days, all of 42nd Street (street, sidewalks, avenues, entire blocks of buildings) was completely off limits to all motorized traffic and most foot and cycle traffic, with only two avenues – one on the East Side (say, 2nd Avenue), and one on the West Side (say, 8th Avenue) – left open to handle all of midtown Manhattan’s North-to-South movements: foot, bicycle, and motorized traffic.

On top of these restrictions on 42nd Street, imagine the entire area encompassing 41st and 43rd Streets – cross streets and all – every inch, being cut off to all motorized traffic for 8 days, except for emergency and police vehicles. Buses would be rerouted out of the area.

Random pedestrians and cyclists approaching from uptown or downtown could move freely within this outlying area immediately to the north and south of 42nd Street, but they could still not access 42nd Street itself, and as they entered into the outlying pedestrian areas through police checkpoints, they would be subject to random bag searches by a police presence resembling that of an occupying army.

Subway service would continue to run uninterrupted through the zone, but would not make any stops on 41st, 42nd and 43rd Streets. All major subway hubs in the area would be completely closed for those 8 days, including MetroNorth and LIRR trains running into and out of Grand Central.

Drivers wishing to travel from, say, the Upper East Side to Kip’s Bay might find it faster and easier at rush hour to take the Queensborough Bridge to the Queens Midtown Tunnel, swinging back again into Manhattan, rather than sitting in the bottleneck forming for blocks and blocks along the approach to the 2nd Avenue 42nd Street southbound crossing.

Imagine in addition that more than half of the width of 42nd Street sidewalks was completely taken up with metal stands and bleachers in preparation for an opening ceremony parade of slow-moving trucks that would traverse 42nd Street from east to west all the way across.

(In Paris, the opening ceremony will feature decked-out boats gliding down the river representing the participating nations, so in addition to the river banks, most of the bridges in the center of Paris are also filled with empty steep metal bleachers.

My fanciful comparison with NYC, unfortunately, doesn’t allow the avenues to behave like bridges, but if you can picture the Park Avenue Viaduct over 42nd Street filled with empty seats and benches stacked high and looking down over the street, you can get a sense of how this vitally important public space has been turned into one vast seating area, sitting idle for 8 days.)

Controlled access to the thousands of residences, businesses, and shops on 42nd Street via the many otherwise closed-off avenues would begin as far away as 41st and 43rd Streets (and sometimes one or two streets farther removed) behind hundreds of feet of the aforementioned chainlink barriers and through select access points guarded by police units 24/7.

Entry would be granted only to authorized individuals in possession of a special QR-coded “Games Pass.”

The “authorized” individuals allowed to enter this area, on foot or on bicycle only, would be: local residents, owners, or employees of shops and businesses on 42nd Street, and/or tourists and others with valid reasons for needing to be there.

The latter reasons would include and be essentially limited to medical appointments, lunch/dinner reservations in restaurants, and the need for guests staying at hotels or Airbnbs within this “secure” perimeter to return to their accommodations.

The QR-coded “Games Pass” itself would be issued to applicants only after the successful submission of detailed personal information and supporting documents to the NYPD well in advance of the shutdown period.

The NYPD would record all the personal information about who lived and worked within this soon-to-be shut-down perimeter, presumably verify the accuracy of the information provided, and then give, or withhold giving, the green light for issuance of the “Games Pass.”

For reasons unknown, many employees of small businesses would never get their QR-coded “Games Pass” after correctly providing all necessary personal information to the authorities.

(In Paris, this inexplicable failure to issue “Games Passes” to employees whose workplaces were inside the locked-down areas, whether due to human or machine error, initially created much tension between cops and workers at numerous access points, as the latter tried by many means (getting their bosses on the phone, showing proof of employment, providing friendly assurances, etc., often in vain, to justify their right and need to enter the area.)

On the afternoon of the opening ceremony, the bleachers lining the sidewalks of 42nd Street, along with the rows of stands looking down from the Park Avenue Viaduct, would slowly fill up with the more than 300,000 ticketed spectators allowed to watch the Olympic Parade.

No one else in NYC – unless they happened to be lucky enough to live in a building on 42nd Street with a window facing the street – would be allowed to get close enough to the event to see it with their own two eyes.

It’s hard to capture the universal exasperation caused by this 8-day near-total shutdown of the Seine River, its upper and lower riverbanks, the buildings all around it, and most of its bridges.

The rerouting of motorized traffic and resulting colossal bottlenecks around this central part of the city have been an absolute nightmare to taxis and commuters at rush hour – even after the significant reduction in the number of vehicles on the roads following the seasonal exodus of Parisians fleeing the city for summer homes and foreign vacation destinations.

But it’s the restrictions on pedestrian and cyclist movements around the water and riverside areas that have enraged Parisians the most.

Hemmed in and funneled through long narrow spaces between sidewalks and empty roads, local residents and visitors to Paris alike are bristling at the intrusive, intimidating metal fences, which are more in line with the types of structures you would see at a detention center or migrant camp than at an international sporting event.

It’s hard to overstate how violently these unsightly barriers clash with the otherwise beautiful surroundings they are keeping people out of.

All of these restrictions have, not surprisingly, led to a serious dropoff in tourist activities in the area. Restaurants within the cordoned-off “security perimeters” are making 30%-70% less than this time last year. This is the case even in the buffer zones leading up to the river where motorized traffic is prohibited but foot and bicycle access is allowed without restrictions. Terraces and restaurant interiors are empty here too.

(Fortunately, the many other stadium/arena/transformed venues around Paris that will be hosting events in the days following the opening ceremony will not cause similar disruptions to neighboring businesses, interrupting traffic flows in the immediate area only for a few hours preceding and following the events.

In such spots, the QR-Coded Games Pass will play a less important role, and won’t be needed by local residents or shopkeepers because no shops or businesses open to the public will be located on the same site as the sporting venue. Only visitors/spectators to these sites will have to worry about QR codes and QR-coded tickets.)

But to return to the river opening ceremony “security” preparations, in order to monitor the hundreds of access points along the North and South banks of the Seine (as well as to monitor the many other Olympic Games venues around the city), 45,000 police and gendarmes have been mobilized, with thousands pouring into Paris from all over France.

I spoke with about a dozen such officers stationed at checkpoints all along the river, and I asked them how things were going. Most – in carefully chosen words and professional tones — said it was a shitshow.

Interestingly, all the police I happened upon were from other parts of France and most were not at all familiar with Paris and its streets and bridges. So when asked by annoyed locals or confused/lost tourists about how to navigate around the off-limit zones, such officers were often of little to no help.

On the two occasions I witnessed local Parisians ask how to get around a closed-off area, the out-of-town police shrugged and apologetically explained how they weren’t from Paris and didn’t know.

Standing for hours on end at the hundreds of cordoned-off access points, they would repeat calmly and patiently that they were stationed there solely to check passes and make sure unauthorized persons did not get beyond them. It was unreasonable to expect anything more of them, they seemed to be saying.

This led me to ask how the actual process of checking the “Games Pass” – their primary responsibility – was unfolding.

It turns out that the way things were supposed to happen was that a person in possession of a “Games Pass” seeking access to the restricted area also needed to show police a separate ID, and sometimes further proof of what they claimed to be doing in the area (if they didn’t live or work there), at which the police could cross-check the name with the information called up by the QR-code scanner.

But it seems there are not (or at least weren’t as of Monday) enough scanners to go around, and, making matters worse, the scanner screens can’t be read properly on sunny days due to the glare.

So in such situations – which also include instances of people not receiving their “Games Pass,” or having lost their paper copy – the police have to “use their best judgment,” and let people through on the basis of simple ID checks and the believability of the person’s story for needing to be in the off-limits area.

The police officers I spoke with said a small number of people, like myself, objected to the use of QR-coded passes on principle, saying that it reminded them of the health and vaccine pass nightmares and that hosting an international event was no justification for denying freedom of movement in this way.

When I asked what they themselves thought of the kennel-like security restrictions, and if they agreed with any of the freedom of movement concerns raised by angry residents, most seemed to miss the point entirely. They would invariably utter something about the size and scope of the event requiring the extraordinary security measures, that terrorists would be plotting, etc. Almost like a pre-recorded message (though eloquently conveyed).

But one cop I spoke to at length raised another issue I hadn’t thought of keeping the entire city away from the Seine for 8 days and nights was also aimed at preventing the newly cleaned river from filling up with human garbage again.

The banks of the river in the warm summer months are thronged with revelers all through the evenings, and this leads to tons of junk and pollution ending up in the water.

It turns out that 1.4 billion euros went into a massive 6-year river cleanup project, beginning in 2018, to make the Seine safe enough to swim in for the handful of aquatic events set to take place in it this summer.

E coli and other bacteria seem to have disappeared (or at least no longer pose a threat to human health) and the number of fish species has made a huge comeback, jumping from 3 to 30 in the last few years due to the significant increase in oxygen in the water.

Understandably, the Olympic Games organizers and the City of Paris didn’t want flotsam in the form of empty wine bottles to be seen bobbing up and down between the parade boats on the opening night, so they decided not to take any chances and simply banned everyone from getting within spitting distance of the water.

This got me thinking.

This whole 8-day Seine shutdown – which in some ways amounts to privatizing the river, making access available to only a fraction of the tax-paying population – could not have been imaginable without the availability of digital passes such as this QR-coded “Games Pass,” which can store and instantly call up huge amounts of pre-vetted personal data.

Though there aren’t enough of the scanners to go around, there are enough to just about make it all work.

Without such on-the-spot digital data-storage technology, the thousands of local residents and other “authorized” persons needing to access the areas around the river on a daily basis would have to carry around with them at all times: IDs, proof of residence, and proof of employment papers. And they would need to show them all every day to every cop they came across at the checkpoints.

Police stationed at these checkpoints, in turn, would have to spend endless time cross-checking all these documents, and querying every non-resident about their purpose for being in the area – a mini-interrogation each time a local resident or worker sought to cross an access point.

It’s hard to imagine the proposal to shut down the Seine River for over a week being taken seriously even in an informal spitballing session of city counselors (let alone in a national-level ministerial meeting) if it involved local residents living by the river having to produce reams of documentation every time they came back from work or the supermarket.

One would hope that such an imaginary discussion, after eliciting groans at the idea of such intrusive on-the-spot background and ID checking by police, would have quickly led to other considerations being raised, such as freedom of movement and the unreasonable obligation to justify one’s presence in public areas.

So there had to be a way to streamline such an extensively coordinated, large-scale shutdown of a heavily populated urban area requiring such tight control of people and their movements, ideally, without people taking too much notice of the personal intrusions and infringements on certain rights and freedoms.

Cue the QR-coded “Games Pass.”

Had there been no sophisticated QR-coded tools to facilitate such an undertaking, it’s likely the hair-brained and outrageous idea of emptying out and privatizing the center of a major metropolis – with all its attendant civil rights questions – would have been immediately apparent.

One wonders if questions over the feasibility and legality/constitutionality of such a proposal were ever brought up in official discussions in 2016. Perhaps, instead, the fascination with the vast organizational and control/surveillance potential of the QR-coded “Games Passes” caused such concerns to be dismissed or downplayed – or eclipsed entirely – once again revealing the dangerous hidden biases of these digital technologies.

In my experience, asking proponents of surveillance/control tools like QR-coded “Games Passes” or Health/Vaccine Passports about the totalitarian nature of the use cases that such technologies inevitably give rise to typically elicits ironic eye-rolling and accusations of alarmism, followed by reassurances about the benefits of enhanced security on a limited time scale.

In the case of the Paris “Games Pass,” such enthusiasts are also quick to highlight the added bonus of having a cleaned-up river to enjoy going forward. The 100-year ban on swimming on the Seine is set to be lifted after the Summer Games, with the opening up of select swimming areas along the river next summer.

But those of us who lived for two-plus years under the totalitarian Corona regime, with its QR-coded health and vaccine passes, see this as a clear attempt to continue testing out these technologies in new contexts involving restrictions on basic rights and freedoms, slowly and steadily conditioning public acceptance of their use in preparation for the inevitable rollout of digital IDs in France and the EU (unless the Europeans start organizing to oppose these out-in-the-open Orwellian plans).

Indeed, it seems the French government misses no opportunity these days to insinuate QR codes into large-scale public celebrations and gatherings where they are not needed.

To wit, the annual Bal des Pompiers (Fireman’s Ball) this year (a uniquely French outdoor celebration held inside the courtyards of Fire Stations all over France on the 13th and 14th of July, which is free and open to the public and draws massive crowds of revelers, featuring the presence of French Foreign Legionnaires and other elite military personnel), for the first time ever, prohibited the use of cash and credit cards for purchases of food and drink and instead required partygoers to buy a QR-coded “credit card” at the entrance.

In order to consume food or alcohol within the firehouse, one had to line up at a special booth and exchange money for a special one-off QR-coded plastic card (the size and shape of a credit card) which then became the only accepted form of currency for purchases during the all-night outdoor celebration.

Unlike previous years, where the firemen serving food and alcohol also handled cash and credit cards, this year they were armed with little scanners, with which they beeped and deducted credit from these disposable digital money cards.

It introduced a wholly unnecessary, illogical, time-wasting step into the normal “money-food” transaction process on the grounds that it would streamline the handover of food and drink in an extremely busy and crowded space by freeing vendors from the need to handle money.

It of course did exactly the opposite, causing people to waste more time standing in the QR-coded card line each time they wanted to buy or top up their card. Worse still, drunk party-goers undoubtedly lost hundreds, if not thousands of euros, from putting more money on their QR-cards than they were able (or remembered) to spend on food and alcohol during the rollicking festivities.

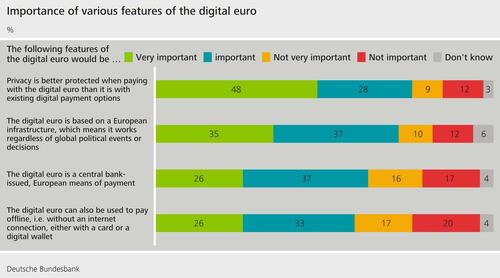

To those of us still reeling from the use of the health passes, it was a terrifying, flagrant further example of the incremental social engineering that has been going on in Europe for the last 4 years, with its two-fold aim of phasing out cash while preparing the public for a sudden shift to a digital euro during the next manufactured emergency.

I can only hope the uproar caused by the Summer Games’ disruptions to people’s ability to live, work in, and enjoy their city will shine a light on these dangerous technologies of control and surveillance that I believe are irreconcilably incompatible with the values and principles of a free society.