Authored by Charles Hugh Smith via OfTwoMinds blog,

Did wages rise 10-fold to match the 10-fold rise in the cost of a modest house? No. That is social recession in a nutshell.

A reader asked about the term social recession which he’d noted in my book Get a Job, Build a Real Career and Defy a Bewildering Economy. Here is the paragraph:

“Stagnation in opportunities to work and earn (i.e. a financial recession) leads to social recession, a loss of opportunities for adulthood: a rewarding career, family, and a home of one’s own. In a social recession, unemployed young people may be mired in adolescent narcissism, eschewing ambitions not just in work but in romance and marriage.”

The reader asked if I could recommend any further reading on social recession and I replied that I could not, as the topic is not well-recognized or studied.

In my analysis, social recession refers to the narrowing of opportunities to marry and raise a family, own a home and have a secure livelihood from the vast majority of the populace to an elite selected by fierce competition–a competition few have the means to win, as the winners tend to win by choosing their parents wisely.

In the purely financial / economic terms of growth of GDP, household income, corporate profits and the value of assets, the US has only been in an economic recession for a few months in 2008-09 and at the start of the pandemic lockdown. But when measured by the ability of just about anyone willing to work hard and practice basic frugality to buy a house and start a family, the US has been in a social recession since 2009.

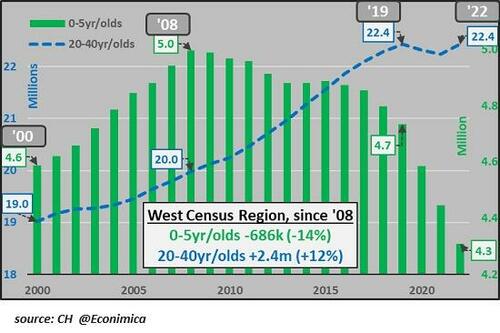

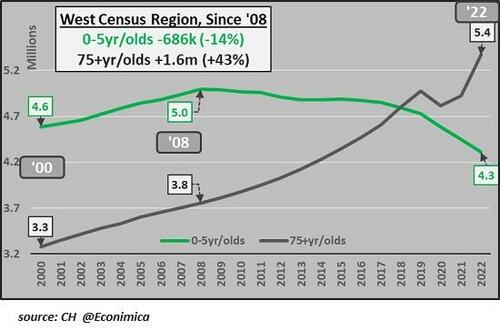

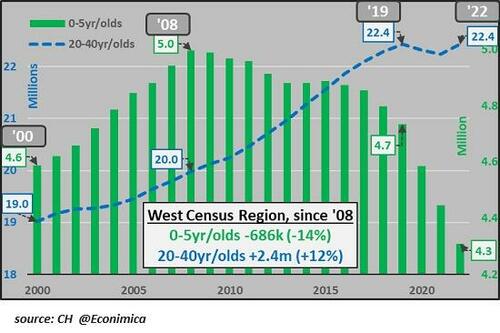

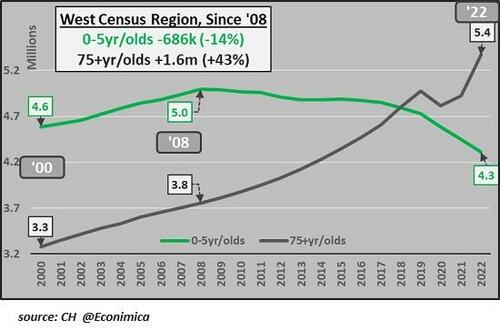

Demographics / economics analyst Chris H., who tweets as CH @economica, recently posted charts which reflect this social recession, most strikingly in the collapse of the US birthrate that started in 2009. He asked: “The largest childbearing population in US history has gone on strike…maybe we should know why?”

Some might argue that this decline in births is coincidental to the Global Financial Crisis , but since social recession has its roots firmly in the economic opportunities available to the average worker, that argument is specious.

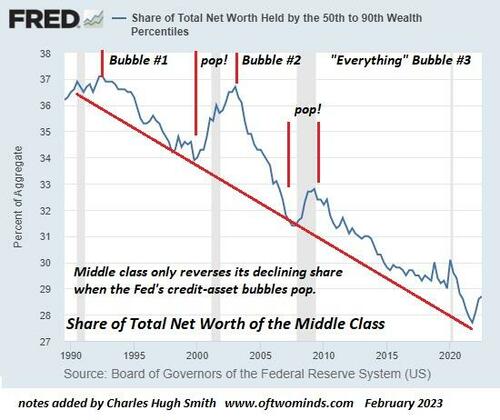

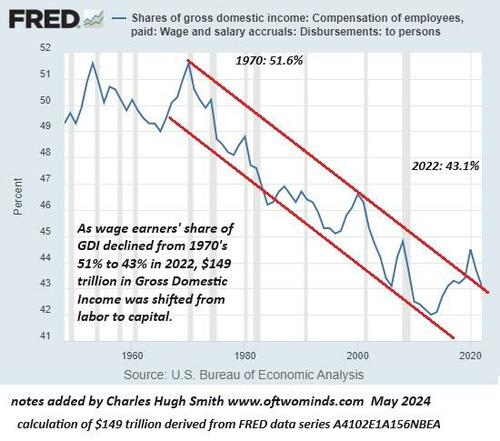

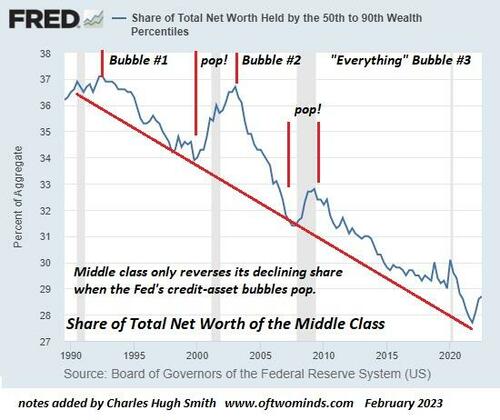

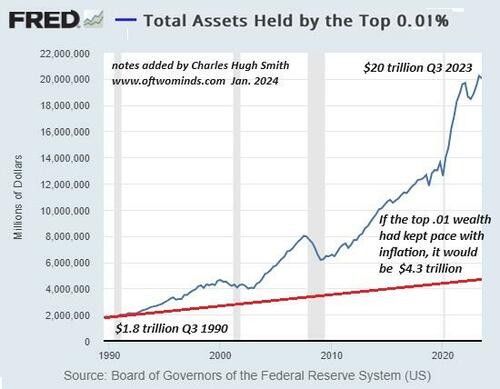

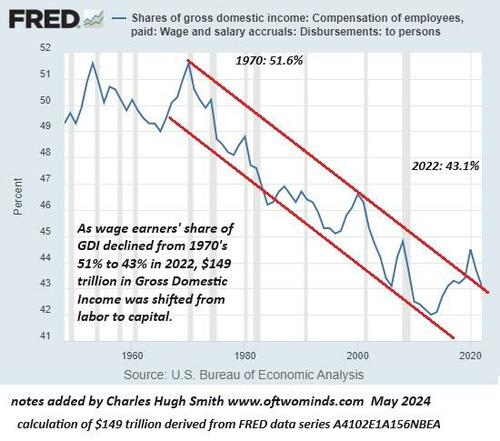

The social recession began as a direct result of policy responses to the Global Financial Meltdown in 2008-09, policies that favored capital and those who already owned assets, at the expense of everyone who did not inherit wealth/assets or was too young to buy assets such as houses when they were still affordable to average workers.

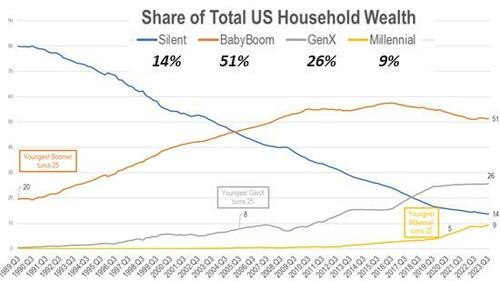

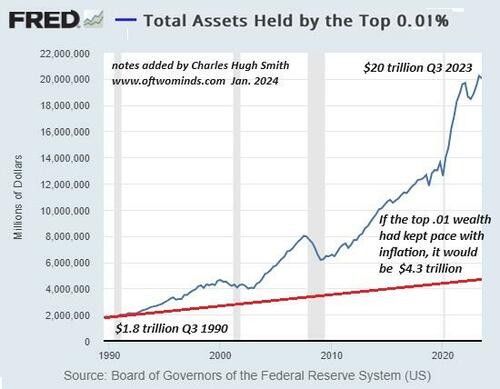

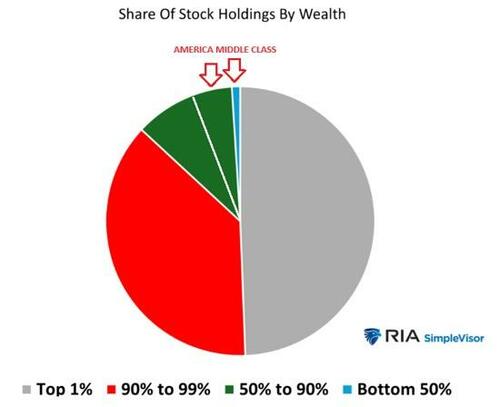

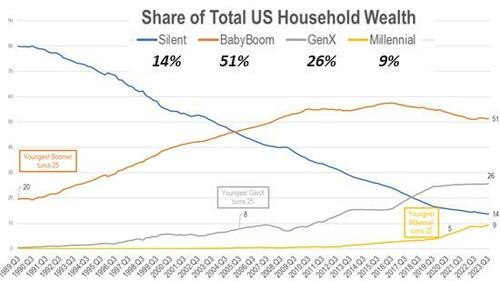

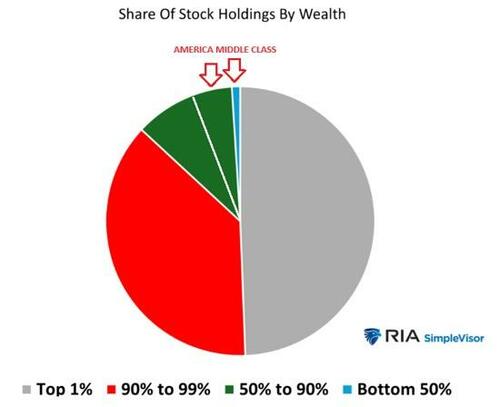

As a result, those who bought assets a generation or two ago now own most of the nation’s wealth:

As I have often discussed in blog posts, aggregate measures of financial expansion (GDP and household net worth) mask the perverse consequence of favoring capital and the already-wealthy: an unprecedented widening of the gap between the top 10% and the bottom 90%, and the concentration of assets in the top 10%.

The spectrum of wealth and income asymmetry has become increasingly asymmetric: the top 01% have pulled away from the top 0.1%, the top 0.1% have pulled away from the top 1%, who have pulled away from the next 9%, and so on. By any measure, the top 20% have left the bottom 80% in the dust, and the bottom 60%’s share of the nation’s wealth is negligible.

As many readers point out to me, education was the key for the post World War II generation on the GI Bill, and it continued to be a critical ladder to higher, more secure incomes from the 1960s to the 1990s. But the premium granted those with any 4-year college diploma has decayed in an inverse relationship with the skyrocketing cost of that diploma.

The diploma by itself has little value outside STEM / medical / legal professions and bureaucracies that use the diploma as a screening mechanism to limit the pool of applicants. Many professions such as law are oversupplied with applicants holding law degrees, and so entry wages outside elite firms are lower than those offered to experienced welders. As the premium on a diploma has eroded, the demands on workers have risen sharply across the entire spectrum of paid work.

As I often note, average wages have stagnated for the past 45 years. This stagnation was tolerable as long as the cost of a house, childcare and healthcare insurance remained somewhat affordable to average workers, but once the engines of financialization transformed the US economy into a Bubble Economy of soaring real estate / stock valuations that then inevitably crash, triggering an even larger bailout / stimulus response that inflates an even greater bubble, the costs of home ownership, childcare and healthcare soared out of reach of all but the top 20% unless family wealth and connections gave younger workers a boost.

Another aspect of social recession is the decay of pensions and the resulting rise of insecurity. Government and government-funded sectors such as healthcare are the only employers that still offer a pension that isn’t the responsibility of the worker to partially or totally fund and manage.

Japan is held up as an example of social and economic stability, but those who know a wide spectrum of Japanese people (i.e. not just academics and corporate leaders) know that Japan has been in a social recession since its bubble burst in 1989-90. The decay is visible but since it’s embarrassing, it’s not covered in the media: abandoned vehicles littering the countryside, Hikikomori (extreme voluntary social isolation), falling rates of marriage and births, the estrangement of family members, pensioners openly shoplifting to get arrested so they can get the full meals and healthcare offered the imprisoned, to name a few manifestations of social recession.

The fact that none of this is visible in the bustling districts of Tokyo and Kyoto doesn’t mean the social recession isn’t real. Japan has managed its decline well, but that doesn’t mean it’s not in social recession.

One aspect of social recession I have discussed is social defeat: when people give up on dreams and goals that are unreachable and so they give up trying.

Many readers share their own experiences of pursuing extreme frugality and hard work back in the day, as evidence that similar efforts will result in the same stability and security they now enjoy. I have recounted my own story of working my way through university, building our own house with our own hands, etc., but when I do a statistical analysis of costs today, I see an unbridgeable chasm between what I could earn 25 years ago and what I could buy with my earnings / savings 25 years ago, and what I can earn and buy today.

I say this as someone who never earned a lot of money; more often than not, I earned far less than the average annual pay of average workers. Having been self-employed most of my working life, I have financial records and clear memories of wages, prices and costs over the past 50 years.

I can state as a fact that two part-time city librarians could still buy a modest home in the San Francisco Bay Area in the late 1990s, and afford to have two children. This is no longer the case–not even close. No amount of frugality can close the gap when the house they bought for $135,000 now costs $1.35 million, and childcare and healthcare have become equally unaffordable.

Did wages rise 10-fold to match the 10-fold rise in the cost of a modest house? No. That is social recession in a nutshell. When this fact is raised in conversation, those in the top 10% protest, but their protest rings hollow, for what they’re really saying is: since I’m doing great and all my friends are doing great, everyone’s doing great. There’s a word for this: denial. Denial cannot solve problems, it can only make them worse.

* * *

Become a $3/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

Subscribe to my Substack for free