Authored by Matthew Hornbach, head of global interest rate strategy at Morgan Stanley

When the history books are written on central banks and markets, the past two months will go down as a couple of the

most fascinating on record. From its December high on the first day of the month to its low on the 24th, the S&P 500 fell

16%. That dramatic drop, among the declines in other risky asset prices, prompted the Federal Reserve to assuage

investor concerns in the first week of January by invoking the word “patient”. Analysts of Fedspeak knew that meant

inaction at the next two FOMC meetings, effectively taking the March rate hike off the table. Since then, the S&P 500 is up

about 8% as of Thursday’s close.

On that nervous January 4th, when Chair Powell first used the word “patient”, he also said that “if [the FOMC] ever came

to the conclusion that any aspect of our normalization plans was somehow interfering with our achievement of our

statutory goals, we wouldn’t hesitate to change it, and that would include the balance sheet certainly”. Throughout the

rest of January, investors would send a clear message: If the Fed wanted financial conditions to help in achieving those

statutory goals then, at a minimum, holding off on further hikes would be a good place to start.

To many market observers, including those on the FOMC, January’s price action may have suggested something else as

well: What happened in 4Q18 was not about balance sheet normalization. However, we think that jumping to such a

conclusion will not serve investors well in 2019, nor will trying to pin the blame for what happened in 4Q on any single

factor. By our measures, financial conditions were on a tightening path through most of 2018 and one that began,

importantly, after the balance sheet began to normalize. Coincidence? We think not.

As we discussed in our recent note, Insight into the Balance Sheet, we believe the shrinking of the Fed’s balance sheet, in

conjunction with higher risk-free rates, causes private sector portfolios to rebalance away from risky assets and toward US

Treasuries and agency MBS. This portfolio rebalancing – known as the portfolio balance channel effect – has been taking

place all year in increasingly larger volumes. The 4Q rebalancing simply happened to coincide with a period of reduced

liquidity and softening growth expectations, both at home and abroad. Of course, the environment in which portfolios

rebalance matters. And the environment in December was not supportive of de-risking flows.

It’s worth emphasizing how portfolio rebalancing works in conjunction with interest rate levels to move markets. With

quantitative easing (QE), the Fed removed assets of long duration (Treasuries and agency MBS) and replaced them with

assets of zero duration (cash). This occurred just as the incentive to own longer-duration assets of all kinds – e.g.,

corporate debt and equities – was rising, thanks to near-zero yields on shorter-duration assets. As a result, portfolios

rebalanced toward scarce, riskier assets of longer duration, which drove prices higher.

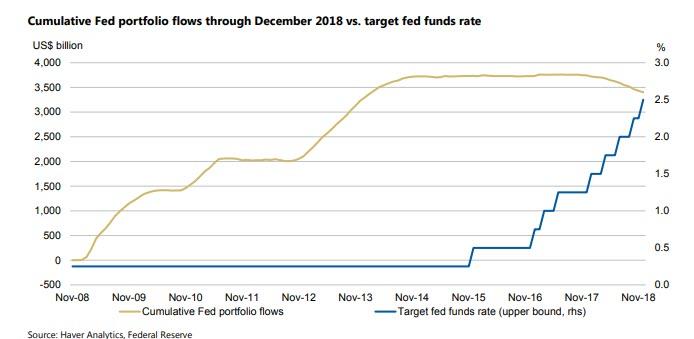

With balance sheet normalization, or quantitative tightening (QT), the Fed is removing assets of zero duration and,

indirectly, replacing them with assets of longer duration. If the policy rate were still near zero, the relative demand for

longer-duration assets might remain robust, even in the face of higher supply. However, the Fed is implementing QT with

a much higher policy rate (see Exhibit), leading to higher demand for shorter-duration assets. As a result, portfolios are

rebalancing away from riskier assets of longer duration, and this is now driving prices lower.

This framework suggests that the Fed’s decision to exercise more patience in raising rates further should prevent

accelerated de-risking for now. At the same time, the previous incentives to de-risk still exist, and the Fed continues to

force portfolio rebalancing. As a result, we expect that underlying financial conditions will tighten further as de-risking

continues. We think that tightening will be driven by lower risky asset prices, while lower US Treasury yields act as a

partial offset. Helped by a more patient Fed, 10-year Treasury yields should end the year at 2.45%.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2RPunNk Tyler Durden