The Farm Belt helped cement President Trump’s historic electoral triumph over Hillary Clinton. But even before Trump started his trade war with China nearly one year ago, Trump’s protectionist bent has added to the collective woes of farmers, who were already struggling with low prices for corn, soy beans and other agricultural commodities.

China’s decision to purchase millions of soybeans (after orders ground to halt late last year following another round of tariffs) offered some relief to soybean producers who were teetering on the brink even with President Trump’s farm bailout money in hand. But even if negotiations result in a lasting agreement, it might not be enough to save hundreds of American family farms from collapsing into bankruptcy, as the Wall Street Journal pointed out in a story published Wednesday.

According to a WSJ analysis of federal data, the number of farmers filing for bankruptcy has climbed to its highest level in a decade…

…driven by a lasting slump in agricultural commodity prices due in large part to the rise of rival producers like Brazil and Russia.

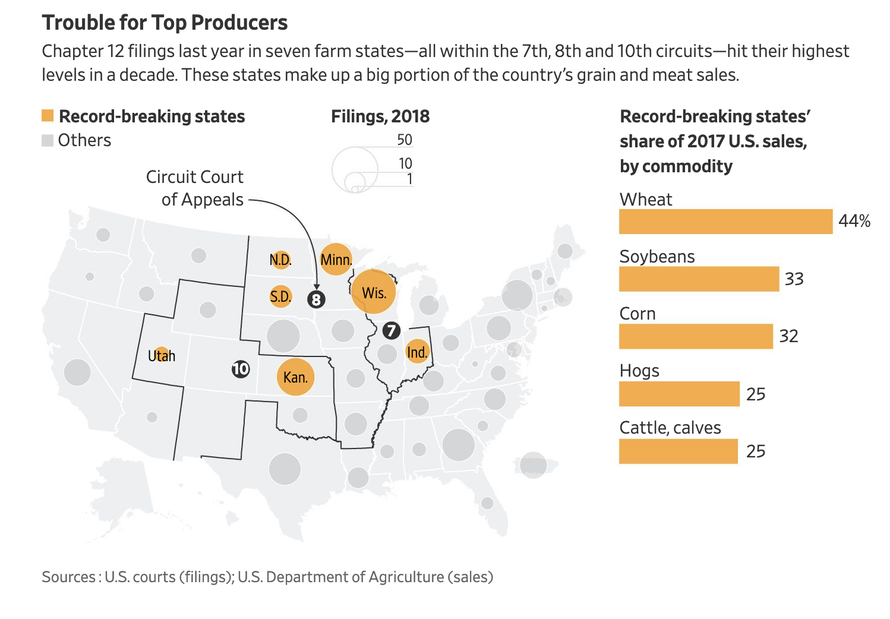

Bankruptcies in three regions covering major farm states last year rose to the highest level in at least 10 years. The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, which includes Illinois, Indiana and Wisconsin, had double the bankruptcies in 2018 compared with 2008. In the Eighth Circuit, which includes states from North Dakota to Arkansas, bankruptcies swelled 96%. The 10th Circuit, which covers Kansas and other states, last year had 59% more bankruptcies than a decade earlier.

And Trump’s trade wars – not just with China, but more broadly – aren’t helping.

Trade disputes under the Trump administration with major buyers of U.S. farm goods, such as China and Mexico, have further roiled agricultural markets and pressured farmers’ incomes. Prices for soybeans and hogs plummeted after those countries retaliated against U.S. steel and aluminum tariffs by imposing duties on U.S. products like oilseeds and pork, slashing shipments to big buyers.

Low milk prices are driving dairy farmers out of business in a market that’s also struggling with retaliatory tariffs on U.S. cheese from Mexico and China. Tariffs on U.S. pork have helped contribute to a record buildup in U.S. meat supplies, leading to lower prices for beef and chicken.

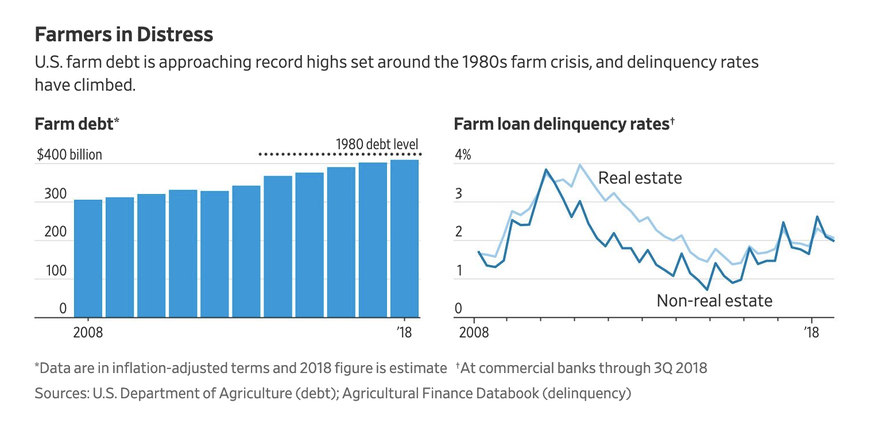

Because of this, the level of farm debt is approaching levels last seen in the 1980s.

The stress on American farmers is also affecting agribusinesses giants like Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge and Cargill, who are feeling the heat even as lower crop prices translate into less-expensive raw materials for the commodity buyers.

What’s worse is that even after working side jobs to try and make ends meet, some farmers are still winding up more than $1 million in debt.

Mr. Duensing has managed to keep farming, hiring himself out to plant crops for other farmers for extra income and borrowing from an investment group at an interest rate twice as high as offered by traditional lenders. Despite selling some land and equipment, Mr. Duensing remains more than $1 million in debt.

“I’ve been through several dips in 40 years,” said Mr. Duensing. “This one here is gonna kick my butt.”

Even more shocking than the number of bankruptcies, the number of farms that continue to operate while losing money has risen to more than half of all farms, even as the level of productivity has never been higher.

More than half of U.S. farm households lost money farming in recent years, according to the USDA, which estimated that median farm income for U.S. farm households was negative $1,548 in 2018. Farm incomes have slid despite record productivity on American farms, because oversupply drives down commodity prices.

And bankers who lend to farms warn that there will likely be more bankruptcies to come as more producers “are running out of options.”

Agricultural lenders, bankruptcy attorneys and farm advisers warn further bankruptcies are in the offing as more farmers shed assets and get deeper in debt, and banks deny the funds needed to plant a crop this spring.

“We are seeing producers who are running out of options,” said Tim Koch, senior vice president at Omaha, Neb.-based Farm Credit Services of America, which lends to farmers and ranchers in Iowa, Nebraska, South Dakota and Wyoming.

Perhaps the only silver lining – if you can even call it that – is that bankruptcy lawyers in states where farms are prevalent are doing their best business in years.

Mounting stress in the Farm Belt has meant big, if somber, business for the region’s bankruptcy attorneys. In Wichita, Kan., the firm of bankruptcy attorney David Prelle Eron filed 10 farm bankruptcies in 2018, the most it has ever handled in one year. Wade Pittman, a bankruptcy attorney based in Madison, Wis., said his firm filed about 20 farm bankruptcies last year, ahead of past years, and he said he expects the numbers to continue to rise as milk prices remain stagnant.

Joe Peiffer, a Cedar Rapids, Iowa-based attorney, said his office is the busiest—and most profitable—it has ever been. Just before Christmas, he sent letters to eight farmers declining to represent them because he didn’t have sufficient staff to handle their cases promptly. He is doubling his office space and interviewing new attorneys to join the firm.

One factor driving bankruptcies is tighter lending standards, said Mr. Peiffer, including at agricultural banks, which are under pressure from regulators to exercise greater caution over their farm-loan portfolios.

“I’m dealing with people on century farms who may be losing them,” said Mr. Peiffer, whose own father sold his farm in the late 1980s.

One anecdote featured in the story recalls the rash of suicides among NYC cab drivers, who have struggled to pay the hefty loans attached to their taxi medallions thanks to the rise of Uber, Lyft and other ride sharing apps.

Darrell Crapp, the fifth-generation owner of a hog and cattle farm in Lancaster, Wis., returned to his home one day with a queasy feeling in his stomach, only to find his wife unconscious on their bathroom floor. She had swallowed a handful of pills. She survived, but Crapp attributed the incident to financial stressors as their farm teetered on the brink of bankruptcy.

It was a Sunday in April 2017 when a queasy feeling in Darrell Crapp’s stomach sent him rushing home. He found his wife, Diana, lying crumpled on the floor of their Lancaster, Wis., bathroom. She had swallowed a handful of pills.

Overwhelmed with debt and with little prospect of turning a profit that year, the Crapps knew BMO Harris Bank NA wouldn’t lend them money to plant. The bank had frozen the farm’s checking account.

Mrs. Crapp managed the fifth-generation corn, cattle and hog farm’s books. She had stayed up nights drafting dozens of budgets to try to stave off disaster, including 30-day, 60-day and 90-day budgets.

“It was too much for her,” Mr. Crapp, 63, said of his wife, who survived the incident.

Crapp Farms filed for chapter 11 bankruptcy the next month, with a total debt of $36 million.

After filing for bankruptcy, the last of Crapp’s land, a 197-acre patch that was homesteaded by his ancestors in the 1860s, will be auctioned off in the near future.

And after all that, Crapp may still need to declare Chapter 12 bankruptcy, a personal bankruptcy provision available to farmers and fishermen, to wipe his remaining debts.

“We haven’t won very many battles,” said Mr. Crapp. “The bank pretty much owns us.”

Unfortunately for American farmers hoping to reclaim the market share they’ve lost during the trade war with China, even if Trump can strike a trade deal with the Chinese that mandates purchases of US agricultural products – which the Chinese have already pledged to do – there’s still another wrinkle: Japan recently signed a revamped version of the TPP that will offer preferential treatment to Australia, New Zealand and other rivals to American farmers, potentially sealing off another market from US agricultural products.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2TDMFOy Tyler Durden