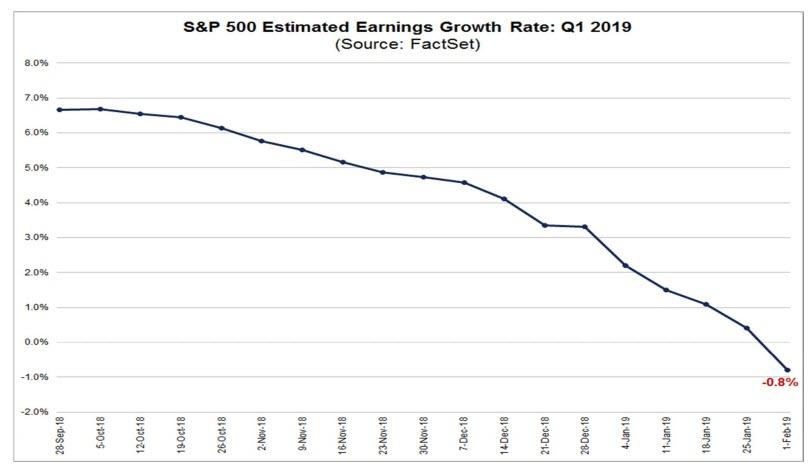

With markets transfixed by the recent dovish reversal by the world’s central bank, which started by the Fed and continued with ECB, RBA, RBI and BOE, while paying increasingly more attention to the upcoming Q1 earnings recession which – for first time since 2016, Q1 2019 is now expected to post a Y/Y contraction in EPS…

… and the recent wave of soft economic data — especially from Europe — amid renewed concerns over prospects for the U.S./China trade talks, the post-Christmas global rally finally took a break, with world stocks posting their first weekly drop after 6 consecutive weeks of increases. Indeed, after brushing up against the 200-day moving average earlier this week, the S&P 500 dipped through the back-half amid trade jitters. In tandem, longer-term Treasury yields revisited levels not seen since the opening days of the year (the 30-year fell below 3%). And while the rally in North American bonds has been impressive, it can’t hold a candle to the move in German bunds, where the 10-year yield has careened down to just 8 bps (yes, 0.08%) from a peak of 77 bps almost exactly a year ago. Completing the risk-off move this week, the U.S. dollar took a small step forward and oil prices sagged somewhat.

And as BMO chief economist Douglas Porter writes, “the main driver for this week’s moderate market angst was not the State of the Union, it was the State of the Global Economy” adding that a suddenly much more subdued tone around the negotiations with China—which resume in Beijing on February 14, at a “high level”—rattled the cozy consensus that a half-loaf deal could be reached by the March 1 deadline, especially since as Trump confirmed, the two presidents are not going to meet before then, “suggesting that an extension of talks may be the best possible outcome at this point.”

Here the BMO economist repeats that no matter what the near-term posturing suggests, a successful long-term US-China trade deal is virtually impossible:

Consider, for example, the painful NAFTA negotiations: In that case, we had a perfectly good agreement to begin with, a moderate bilateral imbalance (between the U.S. and Mexico), and generally positive relationships between the three, and it took more than a year of hard bargaining. In this case, we have no current deal, a massive bilateral imbalance, the U.S. aiming for structural changes, and two adversaries at the table.

Simply, “there is no way that a full-meal deal can be reached in a short period of time” according to Porter, and that whatever unfolds in the next three weeks, “one would suspect that this issue will hover over markets for many, many months to come.”

And while much of the above is well-known, and largely pried in, Porter notes that on top of ongoing concerns about the outlook for trade, we saw a wave of weak trade and production data looking backwards this week. Why? Recall that it was only in late September that the U.S. imposed the latest round of big tariffs on China (10% on $200 billion of imports), and according to BMO, “the global data may now only be catching up with the resulting chill in activity. Germany, in particular, has been harshly sideswiped by the cooldown in trade, and in China’s economy specifically. As one wag put it, “another day, another piece of terrible German data”.

Indeed, as we noted last week, the stand-out was a fourth consecutive monthly drop in industrial production in December, leaving it down a hefty 3.9% y/y: “That’s weaker than in the depths of the Euro crisis, and cannot be explained away by any special factor as many sectors are flagging.”

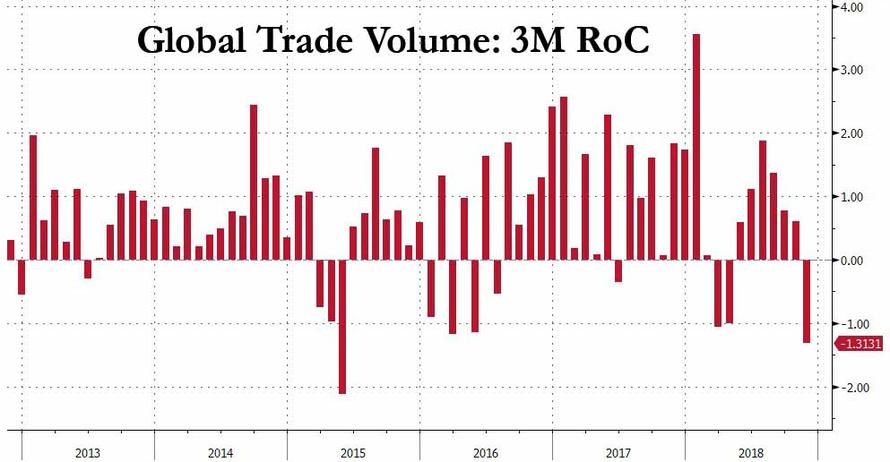

Which brings us to Porter’s punchline, namely a highlight of some of the key “sickly figures” pointing to a notable slowdown in global trade:

The Baltic Dry Index fell to its lowest level in almost three years this week and is now down 44% y/y.

U.S. imports tumbled 2.9% in the (delayed) November trade figures, with the annual increase of 3.2% the lowest since 2016:

A measure of global trade volumes (from CPB) sagged 1.3% in the three months to November, its biggest slide since mid-2015.

In this slowing environment, it is hardly surprising that there has been a wave of downgrades to the 2019 growth outlook in the

industrial world. Most notably, the EU carved its call for GDP this year to 1.3% (from 1.9% as recently as November), while the BoE cut the U.K. call to 1.2% (from 1.7%, also in November). Even Australia got thrown in, with the RBA slicing its GDP outlook half a point (to a still solid 2.75%—this is, after all, the country that hasn’t had a recession since pre-internet days, or around the time the wheel was discovered).

Porter’s conclusion: “while none of the revised forecasts are especially controversial or surprising, the synchronicity of the sudden downgrades is telling, and simply reinforces the point that we are in a very long pause for interest rate hikes globally.”

As for stocks, and how much longer they will ignore the global economic slowdown, it will all depend on whether Powell finally puts his money printing where his mouth is.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2TIKhG8 Tyler Durden