Following years of dismal performance, uncovered attempts at market manipulation and fraudulent activities, and painful corporate reorganizations which its latest earnings report showed have “cut deeply into the muscle”, Deutsche Bank is a shadow of its former self, with its stock price trading just shy of all time lows.

But an even bigger problem for Germany’s biggest lender is that it is now forced to pay the highest financing rates on the euro debt market for a leading international bank this year according to the FT, and also the highest rates among large banks to raise debt this year according to Bloomberg, in a further sign of the German lender’s uphill struggle to turn its operations around and reduce its funding costs.

As the FT first reported, followed promptly by Bloomberg, the bank raised eyebrows last week when it sold a total of €3.6BN in euro-denominated debt, paying 180 bps over the benchmarks for a two-year bond, a steep rate for short-term funding. Deutsche Bank also paid 230 bps over benchmarks for a senior seven-year bond that can absorb losses in a crisis. By comparison, French banking giant BNP Paribas SA last month offered 50 bps less for equally-ranked notes that mature one year later. More embarrassing, Deutsche Bank paid a higher rate than Spanish lender CaixaBank, which recently raised five-year bonds at 225bp.

In a latest note to clients, Corinna Dröse, a Frankfurt-based bond analyst at DZ Bank, said: “The high spreads reflect [Deutsche’s] high idiosyncratic risk, which is rooted in the lender’s chronic weakness in earnings.”

“Deutsche has to pay significantly higher risk premiums than almost all other large European banks . . . [the] high spreads express severe doubts, mainly triggered by its poor revenue,” said Michael Hünseler, head of credit portfolio management at Assenagon.

Intimately linked with the bank’s deteriorating fortunes – and stock price – investors are increasingly demanding that Deutsche Bank pay higher rates of return than even some of Europe’s “most troubled banks” as the firm grapples with a prolonged decline in revenue. Finance chief James von Moltke said last year that the bank was caught in a “vicious circle” of declining revenue, sticky expenses, a lowered credit rating and rising funding costs. While the firm cut expenses, revenue and the price of funding remain a concern.

“A key priority for us now is lowering our funding costs and improving our credit ratings,” von Moltke said during a call with fixed-income investors last week. “We must not compromise on the strength of our capital, funding, or liquidity, but we have to prove that we can generate long-term, sustainable profitability.”

Ironically, DB’s recent funding challenges are a far cry from its “fortress balance sheet” days, as for decades, cheap financing had been the cornerstone of Deutsche’s competitive advantage, with its perception as a “de facto” extension of the German state guaranteeing rock-bottom funding costs that helped it break into the top ranks of global investment banking.

However, Europe’s post-crisis regulations to protect taxpayers from “too big to fail” lenders have eliminated this edge and more recent capital rule changes now require even senior bondholders to take losses if a bank fails, further pushing up costs.

Indeed, the surging interest rate payments could price Deutsche out of transactions with some of its most important institutional and corporate clients, analysts quoted by the FT said, exacerbating market share declines in key businesses. The financing cost rises were another headwind for Deutsche, said Barclays analyst Amit Goel in a report, adding that in an “adverse scenario” for funding, “the bank could face a 35 per cent hit to its pre-tax profit, significantly more than any other European lender.”

Adding insult to injury, there were questions over Deutsche’s decision to tap the debt market with such high rates, despite there being no immediate financing need. One person close to the bank’s supervisory board called the move “insane” although one banker suggested that the lender needed to demonstrate that it had access to the bond markets.

Well, it does… it just cost it a ton of money to “prove it.”

* * *

Even more ironically, last week’s spread-busting bond sale was part of a combined €3.6 billion in bonds issued by Deutsche Bank to bolster capital ratios, i.e. to “appear” safer.

There was a silver lining: DB’s funding costs are still lower than those of Italy’s UniCredit SpA, which paid the equivalent of 420 basis points over the euro benchmark for a private sale in November, at the height of the nation’s budget dispute with European Union officials, as we noted at the time.

Since then however, UniCredit’s spreads have collapsed as traders have wagered that the ECB will not allow either Italy, or its banks to go under. Alas, Deutsche Bank’s future remains far more nebulous, especially since Angela Merkel has vowed taxpayer funds will not be used to rescue the bank.

Deutsche Bank will issue as much as 6 billion euros in covered bonds, as much as 8 billion euros in senior preferred bonds and as much as 11 billion euros in senior non-preferred bonds this year, treasurer Dixit Joshi said.

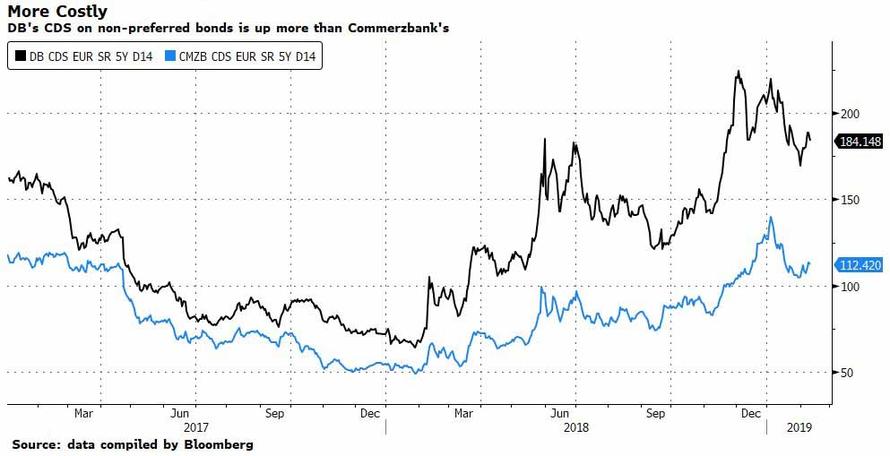

Finally, the bank’s growing troubles have also lit a fire under Deutsche’s CDS: while credit-default swap contracts insuring against a DB bankruptcy have dropped from a two-year high, they’re still more expensive than that of peers like Commerzbank AG. The company’s five-year CDS now trades 20bp wider than Italy’s UniCredit, which is saddled with billions of euros of bad loans.

Last week, Deutsche Bank said that it expects that a contract on its new preferred bonds, which can’t be bailed in in a crisis, will be available to use soon and should be significantly cheaper. Whether or not the market sees through this sleight of hand, and agrees that by raising even more quasi equity, DB will somehow be perceived as safer, remains to be seen.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2tgY4Z5 Tyler Durden