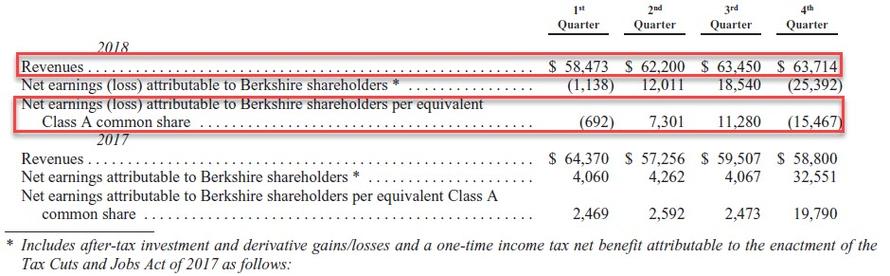

In its latest (surprisingly short at just 14 pages) annual letter released at 8am on Saturday, Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway shocked investors when it announced that Q4 net earnings plunged to a $25.4 billion loss, or ($15,457) per share, from a $32.6 billion profit, or $19,790 per share a year prior, due to an unexpected write-down at Kraft Heinz and unrealized investment losses even as revenues increased from $58.8 billion to $63.7 billion for the fourth quarter, while operating earnings increased from $3.33 billion to $5.72 billion due to increased earnings from Berkshire’s railroads, energy business and other segments.

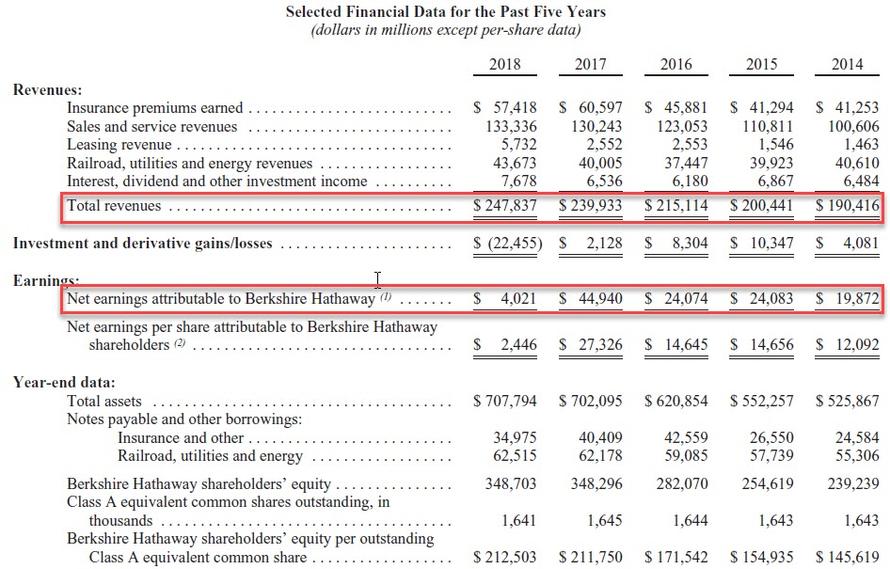

For the full year, Berkshire earned just $4.0 billion in GAAP profits, down 90% from $45 billion the previous year, prompting the WSJ to describe this as “one of Buffett’s worst years ever in 2018.” Separately, in 2018 revenue increased 3% to $247.8 billion, while operating earnings hit a record $24.8 billion. As a reminder, Berkshire’s 2017 earnings soared in the fourth quarter of 2017 due to changes in the U.S. tax law that lowered Berkshire’s deferred tax obligations for stock investments that it currently holds.

What was behind the company’s sharp drop in 2018 earnings, and the massive Q4 net loss? Think of it as the quarter-end marking-to-market of Buffett’s massive equity holdings, coupled with the “unexpected” write-down at Kraft Heinz .

As Buffett explains in his letter, the components of that $4.0 billion full year net earnings figure were $24.8 billion in operating earnings, a $3.0 billion non-cash loss from an impairment of intangible assets (arising from Berkshire’s equity interest in Kraft Heinz which as duly noted here before plunged to an all time low on Friday after a perfect storm of negative news), $2.8 billion in realized capital gains from the sale of investment securities and most notably a $20.6 billion loss from a reduction in the amount of unrealized capital gains that existed in our investment holdings. Similarly, for the eye-popping $25 billion net loss in the fourth quarter, it was driven by $27.6 billion in unrealized losses from the investment portfolio.

Why is this unrealized loss appearing now: as Buffett explains, “a new GAAP rule requires us to include that last item in earnings. As I emphasized in the 2017 annual report, neither Berkshire’s Vice Chairman, Charlie Munger, nor I believe that rule to be sensible. Rather, both of us have consistently thought that at Berkshire this mark-to-market change would produce what I described as “wild and capricious swings in our bottom line.”

A note on Kraft Heinz: the company contributed a $2.7 billion loss to Berkshire in 2018, compared to adding $2.9 billion to its earnings in 2017; Kraft Heinz on Thursday wrote down the value of some of its biggest brands, disclosed an investigation by federal securities regulators and slashed its dividend, sending its stock tumbling.

Lashing out at the new GAAP requirement, Buffett contrasts the wild fluctuations in the bottom line with the steady moves in operating profits:

in the first and fourth quarters, we reported GAAP losses of $1.1 billion and $25.4 billion respectively. In the second and third quarters, we reported profits of $12 billion and $18.5 billion. In complete contrast to these gyrations, the many businesses that Berkshire owns delivered consistent and satisfactory operating earnings in all quarters. For the year, those earnings exceeded their 2016 high of $17.6 billion by 41%.

Buffett then warns that the swings in its quarterly GAAP earnings will “inevitably continue” largely due to because of the company’s “huge equity portfolio – valued at nearly $173 billion at the end of 2018” which will often experience one-day price fluctuations of $2 billion or more, “all of which the new rule says must be dropped immediately to our bottom line.”

Indeed, in the fourth quarter, a period of high volatility in stock prices, we experienced several days with a “profit” or “loss” of more than $4 billion.

How about that for daily trading swings?

Buffett’s advice on how to reconcile these numbers? Simple: just ignore the massive MTM losses and “focus on operating earnings, paying little attention to gains or losses of any variety. My saying that in no way diminishes the importance of our investments to Berkshire. Over time, Charlie and I expect them to deliver substantial gains, albeit with highly irregular timing.”

And while Buffett has traditionally encouraged shareholders to pay attention to Berkshire’s book value over its market value, he said in the letter that market value is now the more relevant metric. In other words, after railing against non-GAAP, Buffett would be delighted if he could present his own GAAP net income as a non- GAAP number.

Irony.

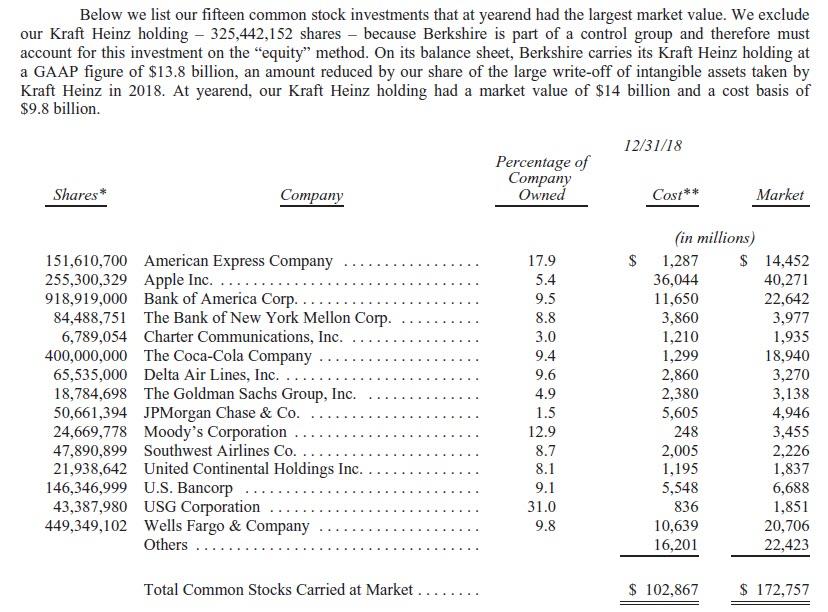

Here is the breakdown of Buffett’s top 15 “capriciously swinging” investments, which naturally took a major hit in the fourth quarter. Of note, the numbers below exclude Kraft Heinz, which is being accounted for as an “equity” investment due to the company’s controlling stake.

Commenting on the portfolio, Buffett said that “Charlie and I do not view the $172.8 billion detailed above as a collection of ticker symbols – a financial dalliance to be terminated because of downgrades by “the Street,” expected Federal Reserve actions, possible political developments, forecasts by economists or whatever else might be the subject du jour. What we see in our holdings, rather, is an assembly of companies that we partly own and that, on a weighted basis, are earning about 20% on the net tangible equity capital required to run their businesses. These companies, also, earn their profits without employing excessive levels of debt.”

Returns of that order by large, established and understandable businesses are remarkable under any circumstances. They are truly mind-blowing when compared against the return that many investors have accepted on bonds over the last decade – 3% or less on 30-year U.S. Treasury bonds, for example

That about covers the nuts and bolts of the quarter, so what about the letter itself.

Massive Cash Pile and Lack Of Investment Opportunities

The first thing that jumps out is Berkshire’s massive cash pile, which was at $112 billion on Dec 31 mostly in the form of T-Bills – marking the sixth straight quarter above $100 billion – showing how difficult it has been for Buffett to put money to work as fast as Berkshire accumulates it, and while Buffett laments the lack of investment opportunities he vows he will never risk getting caught short of cash.

In our fourth grove, Berkshire held $112 billion at year-end in U.S. Treasury bills and other cash equivalents, and another $20 billion in miscellaneous fixed-income instruments. We consider a portion of that stash to be untouchable, having pledged to always hold at least $20 billion in cash equivalents to guard against external calamities. We have also promised to avoid any activities that could threaten our maintaining that buffer.

Berkshire will forever remain a financial fortress. In managing, I will make expensive mistakes of commission and will also miss many opportunities, some of which should have been obvious to me. At times, our stock will tumble as investors flee from equities. But I will never risk getting caught short of cash.

Even with his massive cash holdings, Buffett faces a recurring problem: not enough value investments available, and as he writes in the letter, “in the years ahead, we hope to move much of our excess liquidity into businesses that Berkshire will permanently own. The immediate prospects for that, however, are not good: Prices are sky-high for businesses possessing decent long-term prospects.”

That “disappointing reality” means that 2019 “will likely see us again expanding our holdings of marketable equities”, although Buffett adds that he continues “to hope for an elephant-sized acquisition. Even at our ages of 88 and 95 – I’m the young one – that prospect is what causes my heart and Charlie’s to beat faster. (Just writing about the possibility of a huge purchase has caused my pulse rate to soar.)“

Succession

Buffett letter offered no hints about who will eventually succeed him as CEO. But he did offer praise for deputies Ajit Jain and Greg Abel, saying that decisions to elevate the two men last year into more prominent roles “were overdue.”

I want to give you some good news – really good news – that is not reflected in our financial statements. It concerns the management changes we made in early 2018, when Ajit Jain was put in charge of all insurance activities and Greg Abel was given authority over all other operations. These moves were overdue. Berkshire is now far better managed than when I alone was supervising operations. Ajit and Greg have rare talents, and Berkshire blood flows through their veins.

Stock Buybacks

Berkshire repurchased a bit over $400 million of its stock in the fourth quarter, down from $928 million in buybacks in the third quarter. This may disappoint investors who were hoping Berkshire would spend a significant chunk of its cash buying back shares.

Acquisitions

Some of Berkshire’s 60-odd subsidiaries completed acquisitions, but those deals tend to be small. Berkshire spent $1 billion on bolt-on acquisitions in 2018, the company said, down from $2.7 billion the prior year.

Operating Income

While lamenting the vagaries of GAAP earnings, Buffett said that “despite our recent additions to marketable equities, the most valuable grove in Berkshire’s forest remains the many dozens of non-insurance businesses that Berkshire controls (usually with 100% ownership and never with less than 80%). Those subsidiaries earned $16.8 billion last year. When we say “earned,” moreover, we are describing what remains after all income taxes, interest payments, managerial compensation (whether cash or stock-based), restructuring expenses, depreciation, amortization and home-office overhead.”

And here he once again slammed one of his pet peeves: “adjusted EBITDA” quoting Abraham Lincoln to make his point:

That brand of earnings is a far cry from that frequently touted by Wall Street bankers and corporate CEOs. Too often, their presentations feature “adjusted EBITDA,” a measure that redefines “earnings” to exclude a variety of all-too-real costs.

For example, managements sometimes assert that their company’s stock-based compensation shouldn’t be counted as an expense. (What else could it be – a gift from shareholders?) And restructuring expenses? Well, maybe last year’s exact rearrangement won’t recur. But restructurings of one sort or another are common in business – Berkshire has gone down that road dozens of times, and our shareholders have always borne the costs of doing so.

Abraham Lincoln once posed the question: “If you call a dog’s tail a leg, how many legs does it have?” and then answered his own query: “Four, because calling a tail a leg doesn’t make it one.” Abe would have felt lonely on Wall Street.

Slamming deficit “fear-mongers”

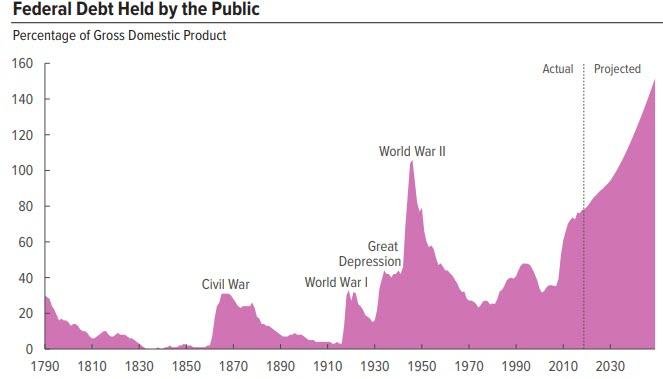

In a surprise twist, the otherwise financially conservative Buffett lashes out at “those who preach doom” because of runaway US budget deficits, and mocks those who – instead – would have put money into gold as insurance against a US collapse. Is Buffett a fan of MMT now?

Here’s the key excerpt:

Those who regularly preach doom because of government budget deficits (as I regularly did myself for many years) might note that our country’s national debt has increased roughly 400-fold during the last of my 77-year periods. That’s 40,000%! Suppose you had foreseen this increase and panicked at the prospect of runaway deficits and a worthless currency. To “protect” yourself, you might have eschewed stocks and opted instead to buy 31⁄4 ounces of gold with your $114.75.

And what would that supposed protection have delivered? You would now have an asset worth about $4,200, less than 1% of what would have been realized from a simple unmanaged investment in American business. The magical metal was no match for the American mettle.

Maybe he is right, but in any case, the good news for Buffett, who is 88, is that he won’t be around to see what happens when, as the CBO predicts, US debt hits 150% in a few decades and rises exponentially from there. As such, with his life almost over, he may have a certain bias toward taking less prudent “long-term” decision.

American exceptionalism and Optimism

His thoughts about the US deficit notwithstanding, Buffett closes with his characteristic optimism about the state of the US economy.

Our country’s almost unbelievable prosperity has been gained in a bipartisan manner. Since 1942, we have had seven Republican presidents and seven Democrats. In the years they served, the country contended at various times with a long period of viral inflation, a 21% prime rate, several controversial and costly wars, the resignation of a president, a pervasive collapse in home values, a paralyzing financial panic and a host of other problems. All engendered scary headlines; all are now history.

Christopher Wren, architect of St. Paul’s Cathedral, lies buried within that London church. Near his tomb are posted these words of description (translated from Latin): “If you would seek my monument, look around you.” Those skeptical of America’s economic playbook should heed his message.

In 1788 – to go back to our starting point – there really wasn’t much here except for a small band of ambitious people and an embryonic governing framework aimed at turning their dreams into reality. Today, the Federal Reserve estimates our household wealth at $108 trillion, an amount almost impossible to comprehend.

Remember, earlier in this letter, how I described retained earnings as having been the key to Berkshire’s prosperity? So it has been with America. In the nation’s accounting, the comparable item is labeled “savings.” And save we have. If our forefathers had instead consumed all they produced, there would have been no investment, no productivity gains and no leap in living standards.

In the above, Buffett touches on two very sensitive points: household wealth, which as Buffett correctly notes, is a record $108 trillion. What he does not discuss is that some 90% of that wealth is in the hands of less than 10% of the US population. Maybe if the Octogenarian of Omaha were to look back at history for similar episodes where a handful of people controlled all the wealth, he would note that the outcomes is usually bloody and violent and involves more than one guillotine.

As for his final paragraph, all we can say is that while just a few paragraphs above Buffett appeared to be advocating for MMT and runaway deficit spending, in the last bolded sentence, the billionaire crushes the Keynesian creed of spending at all costs, and if nothing else, emerges as an Austrian economist where the key to prosperity is saving, not spending.

We wonder how the financial media will reconcile these two.

* * *

Full letter below (pdf link)

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2tyk8hX Tyler Durden