The bizarro world that was unleashed when the world’s central banks took interest rates to zero (and in many cases, lower), coupled with purchases of $15 trillion securities, allowed countless profitless companies to flourish and thrive, with fundamental indicators such as profit margin, cash flow and net income now seen as remnants of a bygone era even as the deflationary tide that these companies unleashed upon the world as they scrambled to capture market share by undercutting prices at every point prompted those same central banks to re-evaluate their very understanding of inflation, seemingly unaware of how their actions made deflation the rule rather than the exception.

But while we have seen countless instances of companies with massive revenues generating razor thin, or negative margins, as they effectively give away money in their pursuit for monopolistic market share, i.e., the hope of putting all their competitors out of business at which point they would finally have pricing power and will crank up prices and fees, and have even observed companies which – like Uber and Lyft – generate ever greater losses even as their revenues rise, we had yet to encounter the shocking “new abnormal” paradigm that was just revealed by one of the “unicorn” darlings spawned by the era of cheap money.

First, here is the good news: WeWork, the company whose communal co-working spaces are populating many of the world’s biggest cities, said that revenue last year more than doubled. Now, the not so good: the company also unveiled that its losses are growing even faster than its revenues.

In a presentation sent to CNBC on Monday, WeWork said revenue in 2018 climbed to $1.8 billion from $886 million a year earlier: an impressive increase of more than 100% to be sure. Digging into the financials shows some impressive trends: members, or the people who pay for monthly use of WeWork’s facilities, jumped to 401,000 from 186,000, accounting for 88% of revenue. The number is even better if one uses the annualized revenue of $2.5 that was revealed by CEO Adam Neumann (who previously populairzed the farcical concept of “community-adjusted EBITDA”) in January.

Here is where things get especially bizarre: while the company’s revenue surged in 2018 to $1.8, this was more than offset by the company’s loss, which in 2018 exploded to $1.9 billion, up from $933 million in 2017.

In other words, not only did the company not generate anything remotely close to a profit: you know, the primary reason for a corporation to exist in the first place, but it spent more than $1 for every dollar it brought in as revenue for the second year in a row. Effectively, WeWork is handing out free money and for what reason? Simple: just like Amazon, it is desperate to undercut its competitors on price in hopes of eventually cornering enough of the market and creating enough pricing power allowing it to one day, somehow, generate a profit.

For now, that moment is far into the future, and until then the company’s generous sponsors will have no choice to keep funding the company’s exponentially growing losses. Indeed, as CNBC notes, WeWork’s business model continues to rely on heavy funding from private investors, namely SoftBank, which has poured over $10 billion into the company, including $2 billion this year, and wil have to keep pouring capital at an alarming pace. WeWork has to plunge cash into real estate in some of the most expensive markets and makes money back over time as companies and individuals pay their rent, or membership.

Perhaps realizing that this is not a sustainable proposition and its investors are starting to lose patience, in January, WeWorks said that it’s rebranding as the We Company as it “intends to expand beyond just work spaces”, or said otherwise, it will find new and even more creative ways to lose money. The company has touted its move into residential living communities, dubbed WeLive, and early education schools called WeGrow. Each of those business segments will run as stand-alone units under the new We Company umbrella. They will also be money-losing for a long time.

Worse, in order to steal away market share, the company not only has to subsidize its customers, but it does so on a long-term basis: the company’s core enterprise members account for 32 percent of the total, up from 23 percent a year earlier according to CNBC. Those customer have longer commitments, generally three to five years, said Artie Minson, WeWork’s finance chief. This means that during the next recession when the company will be in dire need of raising prices as many of its customers go out of business, it will have no recourse to do so for at least a third of its user base, and the cash flow burn will continue.

WeWork’s financials are hitting the market at a time when the company’s peers in the broader sharing economy space are preparing to hit the public markets. Lyft is expected to debut later this week at a valuation north of $20 billion. Its larger ride-hailing rival, Uber, is reportedly not far behind, while room-sharing company Airbnb is also gearing up to go public.

“We’re rooting for everyone’s success,” said Michael Gross, WeWork’s vice chairman, in an interview. “We’re watching it obviously, but it’s not going to dictate our timeline. We have an incredibly strong hand.”

If by ‘strong hand’ he means spending more than one dollar to bring in one dollar in revenue, then he is absolutely correct.

There was some good news, however: by one – absolutely idiotic – metric, which WeWork calls “community adjusted” EBITDA and which is basically earnings before esentially all expense and cost items, the company is becoming “more profitable”: that margin was 28% last year up from 27% a year earlier.

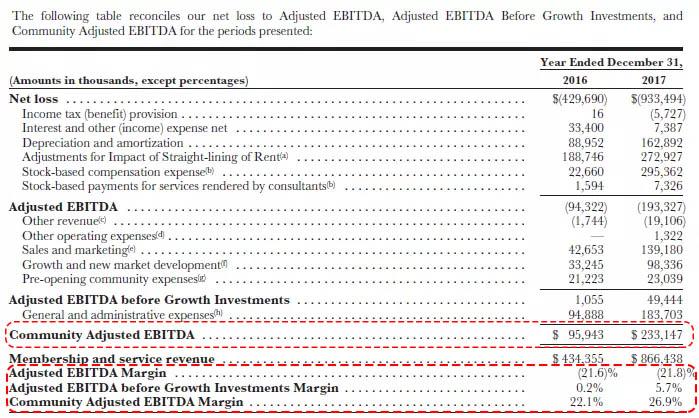

We first caught a glimpse of the non-GAAP wizardy that is “community adjusted EBITDA” last August, when the company first unveiled not just one adjustment to adjusted EBITDA, but an adjustment to the adjustment to the adjustment, which by the miracles of non-GAAP “accounting”, pushed the company’s EBITDA from negative $193 million to positive $233 million in 2017.

This is how the WSJ described this novel line item that would make even a Jefferies bond salesman blush:

“It subtracted not only interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, but also basic expenses like marketing, general and administrative, and development and design costs.”

Additionally, “community adjusted EBITDA” includes all tenant fees, rent expense, staffing expense, facilities management expense, etc. for active WeWork buildings. In other words, it is about as close to revenue as one can make it without being carted off to an insane asylum.

And so, at least according to completely made up numbers, the company is doing what it should.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2Oq28Qq Tyler Durden