Few topics prompt as powerful (and violent) a response from financial professionals as what the role of financial buybacks is in determining stock prices. One group, largely those bulls who after a decade of central bank manipulation still believe that markets are efficient and unrigged, and in hope of increasing their AUMs claim that they are financial geniuses for riding the world’s biggest financial bubble in history, argue that stock buybacks have no impact on stock prices. Others, those who actually understand that if there is a trillion dollars in price indiscrimiante stock bids (as was the case in 2018 and will again happen in 2019) is the single most effective way to boost stock prices (and management’s incentive-linked comp, linked to higher stock prices), know – correctly – that corporate buybacks, which until not too long ago were banned, and which over the past decade emerged as the single biggest source of stock purchases, are one of the two most important factors behind the all time highs in the stock market (the other being the Fed, whose policies have allowed companies to issue debt with record low yields, allowing them to fund these trillions in buybacks).

And with the debate raging, either side happy to “convince” others in its echo chamber while hurling insults at the other, few have been as vocal in their defense of stock buybacks as Goldman Sachs.

One month ago, the firm’s chief equity strategy David Kostin wrote a report – let’s call it the carrot – seeking to debunk “misconceptions” about stock buyabcks, which he claimed had gotten an unfair rap in the US. Specifically, Kostin said that “one of the greatest misconceptions in the public discourse surrounding corporate buybacks is the belief that managements repurchase stock in an attempt to inflate earnings per share and meet incentive compensation targets,” Goldman wrote. And while Goldman tried, to demonstrate that “executives whose compensation depends on EPS, did not allocate a higher proportion of 2018 total cash spending to buybacks than companies where management pay is not linked to EPS”, the bank was forced to admit that last year buybacks did surpass capex as the biggest use of capital allocation.

Goldman’s valiant effort to halt regulatory and legislative focus on buybacks – which also included Goldman’s ex-CEO Lloyd Blankfein issuing a rebuttal defending the practice on Twitter, saying the money “gets reinvested in higher growth businesses that boost the economy and jobs” did little however to stem the tide and as a result buybacks have been getting increasing scrutiny in the wake of the tax reforms in late 2017, when companies used money saved from the lower taxes as well as repatriated cash to return money to shareholders in record amounts, with total announced buybacks surpassing $1 trillion for the first time in 2018.

As a result, Republican Senator Marco Rubio of Florida released a plan last month that would curb buyback incentives. Democratic Senator Chris van Hollen of Maryland may propose legislation curbing executive share sales after repurchase announcements. The culmination – so far – was the US Senate convening hearings and introducing legislation to prohibit public companies from repurchasing their shares on the open market.

This was too much for Goldman, which realized that the carrot approach is not working, and late on Friday went all “stick”, when one month after his first report exposing buyback “misconception”, Goldman’s David Kostin doubled down, effectively warning that a ban on buybacks would likely result in a market crash, as “eliminating buybacks would immediately force firms to shift corporate cash spending priorities, impact stock market fundamentals, and alter the supply/demand balance for shares.”

And just to underscore his dire warning, Kostin said that from a portfolio strategy perspective, “the potential restriction on buybacks would likely have five implications for the US equity market: (1) slow EPS growth; (2) boost cash spending on dividends, M&A, and debt paydown; (3) widen trading ranges; (4) reduce demand for shares; and (5) lower company valuations.”

Kostin then breaks down these core points into the detail components, all of which have dire consequences for the market if the single biggest buyer of stocks is forced to step aside:

1. Slow EPS growth.

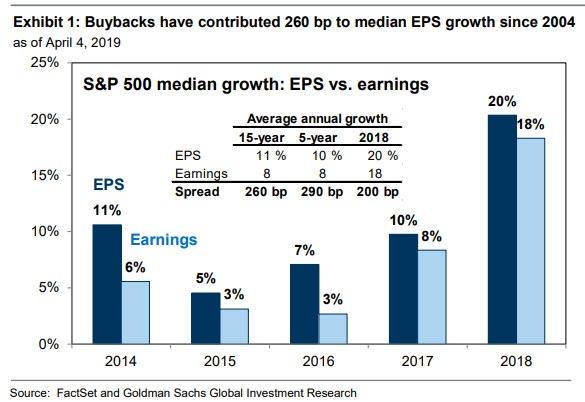

From a fundamental perspective, removing buybacks would have a negative effect on EPS growth. Aggregate earnings growth trails EPS growth because buybacks boost earnings per share by reducing the number of shares outstanding. During the past 15 years, the gap between EPS growth and earnings growth for the median S&P 500 company averaged 260 bp (11% vs. 8%). In 2018, the spread equaled 200 bp (20% vs. 18%). Another approach to estimating the boost to EPS growth in excess of earnings growth is the net buyback yield [(share repurchases – share issuance) / starting market capitalization]. This yield reflects the percent of market cap repurchased during the trailing 12 months. The S&P 500 net buyback yield averaged 2.6% during the past five years, close to the actual 290 bp gap between median EPS and earnings growth (10% vs. 8%).

2. Shift cash spending priorities.

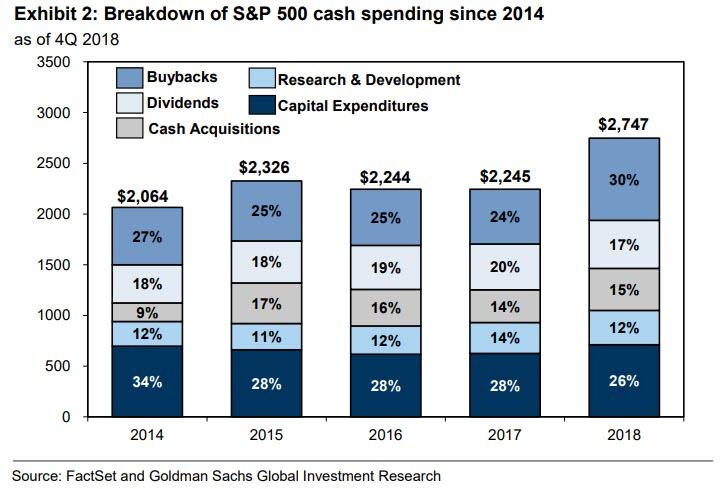

S&P 500 firms allocated an average of 25% of their annual cash spending to buybacks since 2009. Eliminating repurchases would compel firms to find new uses for that cash. Some firms might choose to make formal tender offers for their shares, which firms employed to retire stock prior to 1982. But most managements would probably redirect cash that was previously spent on buybacks towards dividends (both regular and special) and funding more M&A. Spending on capex and R&D would probably not change if buybacks ceased, according to Goldman. During the past decade, capex and R&D have accounted for an average of 45% of S&P 500 annual cash spending which has consistently equaled about 8% of sales. Investment spending has always been the first priority for corporations, at least until 2018 when spending on buybacks surpassed CapEx for the first time. Simply put, to Goldman this means that without new investment opportunities firms are unlikely to suddenly spend more than 8% of sales on capex and R&D, and firms would be forced to hoard the case. This means that in a world without buybacks, companies would almost certainly increase dividend growth and raise cash M&A spending. Dividends have accounted for 18% of annual cash use during the past decade and growth has averaged 6%. The S&P 500 dividend payout ratio currently equals 34%, below the 30-year average of 38%. Cash M&A spending would also jump. During the past decade, cash M&A spending accounted for 13% of corporate cash use and growth averaged 16% annually (Ex. 2). More than 75% of mergers involve some cash consideration. Firms might also choose to redirect cash spent on buybacks to reduce debt outstanding.

3. Widen trading ranges.

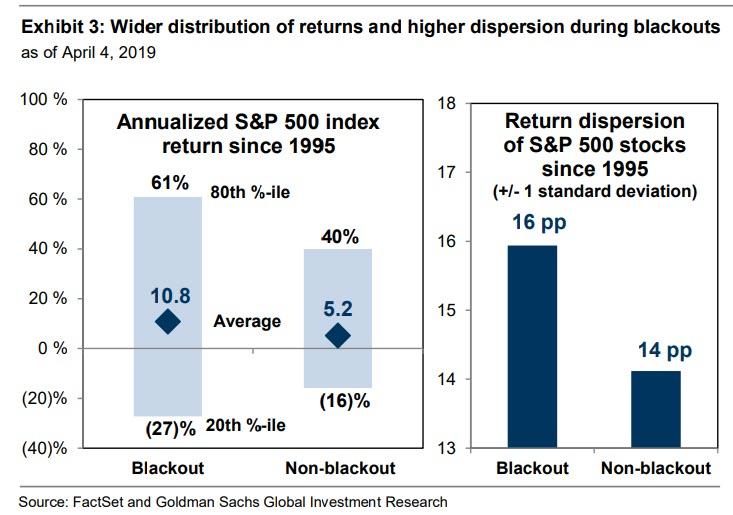

Removing or limiting buybacks would lead to a greater amplitude of index moves, a wider distribution of individual stock returns, and higher volatility: in short many more market crashes, both flash and otherwise. Worse, Goldman notes that prohibiting buybacks would reduce downside support for equity prices since companies could no longer step in to repurchase shares if their stock prices tumble. A case study of the potential impact of eliminating buybacks can be seen each quarter around the time the buyback blackout rolls in, about five weeks prior through two days after a company releases earnings. During these periods, firms are restricted from executing discretionary buybacks.

And here is the clearest indication just how much of an impact buybacks have no stock prices: during the past 25 years, the 20th percentile return for stocks within the S&P 500 has averaged -27% (annualized) in buyback blackout periods compared with -16% when companies can freely repurchase their shares. The average (11% vs. 5%) and 80th percentile (61% vs. 40%) stock returns are also higher during buyback blackouts likely due to the boost from quarterly earnings releases. Return dispersion (16 pp vs. 14 pp) and volatility (16.4 vs. 15.8) during blackout windows have also been higher compared with non-blackout periods (Exhibit 3).

4. Reduce demand for shares

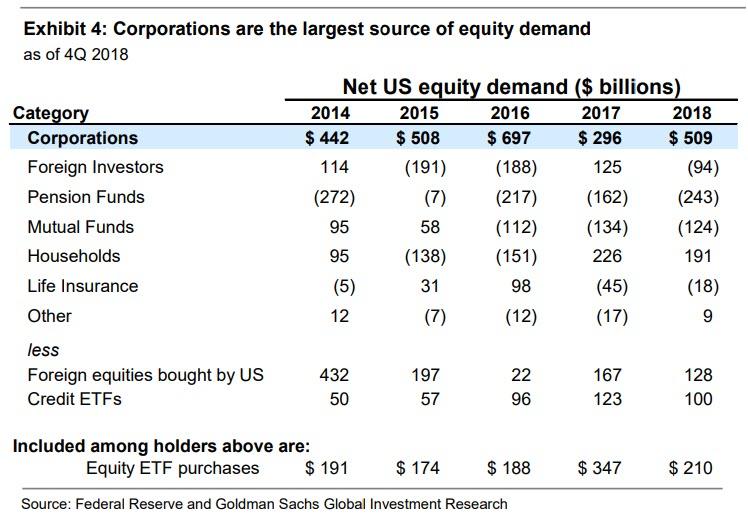

This is where Goldman’s warnings start to get especially dire, because as Kostin cautions, without company buybacks, demand for shares would fall dramatically. Repurchases have consistently been the largest source of US equity demand. Since 2010, corporate demand for shares has far exceeded demand from all other investor categories combined. Net buybacks for all US equities averaged $420 billion annually during the past nine years. In contrast, during this period, average annual equity demand from households, mutual funds, pension funds, and foreign investors was less than $10 billion for each category – despite the fact these categories collectively own 83% of corporate equities. Buybacks represented the largest source of equity demand in 2018.

According to the Federal Reserve’s most recent Financial Accounts quarterly report, corporate demand for stocks, measured as gross repurchases minus share issuance plus M&A, totaled $509 billion last year. Households were the only other net buyer of stocks (+$191 billion). Pensions, mutual funds, and foreign investors sold $243 billion, $124 billion, and $94 billion of equities in 2018, respectively. High equity exposure among major investor categories increases the importance of buybacks as a source of equity demand. Equity allocations for each of the major investor categories are elevated vs. history. Aggregate equity allocation totals 44% across households, mutual funds, pension funds, and foreign investors (86th percentile relative to the past 30 years). In contrast, we estimate that allocation to debt and cash are only at the 39th and 3rd percentiles, respectively.

5. Lower valuations

A decline in expected earnings growth could also lead to P/E multiple contraction. In a world without buybacks, forward EPS growth could be trimmed by 250 bp, close to the impact of net buybacks on company-level EPS growth. During the past 30 years, a 250 bp lower expected FY2 EPS growth has corresponded with a one multiple point lower forward P/E multiple for the median S&P 500 stock. And since Goldman already warned liquidity would be even more dire, one can expect that 1x PE multiple shrinkage to have dire consequences on stock prices.

Finally, prohibiting buybacks could also apply downward pressure to equity prices if it increases the supply of equities relative to demand at current prices, as eliminating the largest source of equity demand could lower the demand curve if other investor categories do not replace the corporate bid from buybacks. And since buybacks have been the go-to backstop for the market – along with the Fed – the probability of another “investor category” stepping up to buy stocks when the buyer of last reserve is gone, is virtually nil.

* * *

So as Goldman turns from a carrot to a stick approach, one can summarize the latest Goldman report by observing that very bad things will happen if Congress proceeds with its intentions to ban buybacks. There is a silver lining: while Goldman previously sided with the generally clueless segment of “financial experts”, claiming that the impact of buybacks on stocks is at best muted, now that buyback legislation is becoming an increasingly greater threat by the day, Goldman can finally admit the truth: without buybacks the market will crash.

And with Goldman’s abrupt and honest reversal, we are confident that the debate whether buybacks influence stocks or not, can finally be laid to rest.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2VobTkO Tyler Durden