Authored by Nouriel Roubini via Project Syndicate,

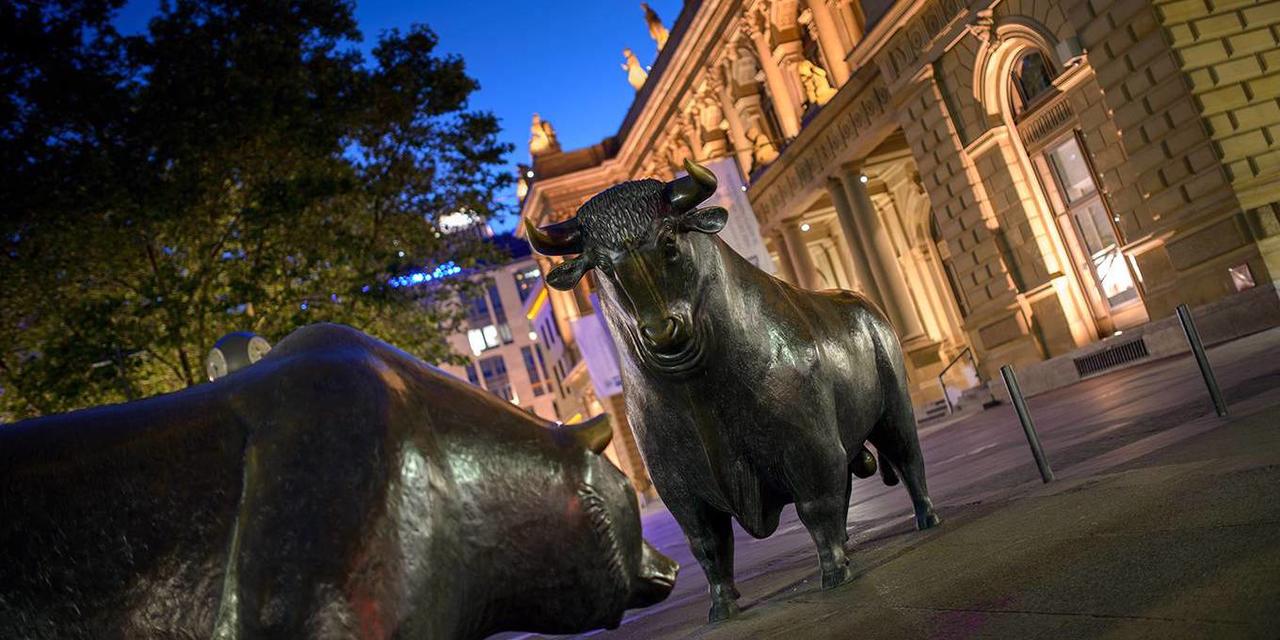

After the global risk-off of late 2018, a newfound dovishness on the part of central bankers has combined with other positive developments to revive investors’ animal spirits. But with a wide array of financial and political risks clearly in view, one should not assume that the current ebullience will last the year.

Financial markets tend to undergo manic-depressive cycles, and this has been especially true in recent years. During risk-ons, investors – driven by “animal spirits” – produce bull markets, frothiness, and sometimes outright bubbles; eventually, however, they overreact to some negative shock by becoming too pessimistic, shedding risk, and forcing a correction or bear market.

Whereas prices of US and global equities rose sharplythroughout 2017, markets began to wobble in 2018, and became fully depressed in the last quarter of the year. This risk-off reflected concerns about a global recession, Sino-American trade tensions, and the Federal Reserve’s signals that it would continue to raise interest rates and pursue quantitative tightening. But since this past January, markets have rallied, so much so that some senior asset managers now foresee a market “melt-up” (the opposite of a meltdown), with equities continuing to rise sharply above their current elevated levels.

One could argue that this latest risk-on cycle will continue for the rest of the year.

For starters, growth is stabilizing in China, owing to another round of macroeconomic stimulus there, easing fears of a hard landing. And the United States and China may soon reach a deal to prevent the ongoing trade war from escalating further. At the same time, US and global growth are expected to strengthen somewhat in the second half of the year, and the disruption of a “hard Brexit” has been averted, with the European Union extending the deadline for the United Kingdom’s departure to October 31, 2019. As for the eurozone’s prospects, much will depend on Germany, where growth could rebound as global headwinds fade.

Moreover, central banks, particularly the Fed, have become super-dovishagain, and this appears to have reversed the tightening of financial conditions that produced the risk-off in late 2018. And on the political front, the chances of impeachment proceedings in the US have fallen sharply with the release of the Mueller report, which clears US President Donald Trump of criminal conspiracy charges (though it is not dispositive on the question of obstruction of justice). Now that the Russia investigation is over, Trump may avoid issuing destabilizing statements (or tweets) that could rattle the stock market, given that it is a key benchmark by which he judges his own success.

Finally, in a positive feedback loop, stronger markets boost economic growth, which in turn can lead to even higher market values.

These developments may or may not ensure clear sailing for the rest of the year. While markets have already priced in the aforementioned positive potentialities, other factors could trigger another risk-off episode.

First, the price-to-earnings ratio is high in many markets, particularly for US equities, which means that even a modest negative shock could trigger a correction. In fact, US corporate profit margins are so high that there could be an “earnings recession” this year if growth remains around 2%, while production costs may increase with a tight labor market.

Second, there are heightened risks associated with the scale and composition of US corporate-sector debt, owing to the prevalence of leveraged loans, high-yield junk bonds, and “fallen-angel” firms whose bonds have been downgraded from investment-grade to near-junk status. Moreover, the commercial real-estate sector is burdened with overcapacity, as developers overbuilt and e-commerce sales have undercut demand for brick-and-mortar retail space. Against this backdrop, any sign of a growth slowdown could lead to a sudden increase in the cost of capital for highly leveraged firms, not just in the US, but also in emerging markets, where a significant share of debt is denominated in dollars.

Third, assuming that US economic growth holds up, market expectations of more Fed dovishness will likely prove unfounded. Thus, a Fed decision not to cut rates could come as a surprise, triggering an equity correction.

Fourth, hopes of a resolution to the Sino-American trade war may also be misplaced. Even with a deal, the conflict could escalate again if either side suspects the other of not holding up its end. And other simmering trade tensions could boil over, if, for example, the US Congress fails to ratify the Trump administration’s revised North American Free Trade Agreement, or if Trump follows through with import tariffs on cars from Europe.

Fifth, European growth is very fragile, and could be hindered by any of a number of developments, from a strong showing by populist parties in the upcoming European Parliament elections to a political or economic crisis in Italy. This would come at a time when monetary and fiscal stimulus in the eurozone is constrained and eurozone integration is stalled.

Sixth, many emerging-market economies are also heavily exposed to political and policy risks. These include (from least to most fragile): Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Turkey, Iran, and Venezuela. And China’s latest round of stimulushas saddled its already indebted corporate sector with even more financial risk – and may not even suffice in lifting its growth rate.

Seventh, Trump may react to the Mueller report with bluster, not prudence. With an eye to the 2020 presidential election, he could double down on his fights with the Democrats, launch new salvos in the trade war, stack the Fed Board with unqualified cronies, bully the Fed to cut rates, or precipitate another government shutdown over the debt ceiling or immigration policy. At the same time, the Trump administration’s approach to Iran and Venezuela could put further upward pressure on oil prices – which have rallied since last fall – to the detriment of growth.

Finally, we are still in a world of low potential growth – a “New Mediocre” sustained by high private and public debt, rising inequality, and heightened geopolitical risk. The widespread populist backlash against globalization, trade, migration, and technology will all but certainly have an eventual negative impact on growth and markets.

So, while investors’ latest love affair with equity markets may continue this year, it will remain a fickle and volatile relationship. Any number of disappointments could trigger another risk-off and, possibly, a sharp market correction. The question is not whether it will happen, but when.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2UO2yGU Tyler Durden