The last time we did a closer look at China’s bad debt, a topic that has been particularly sensitive for an economy whose financial sector is now over $40 trillion, was in late 2015 when CLSA stumbled on what we then dubbed China’s “neutron bomb”: Chinese banks’ bad debts ratio could be as high 8.1% a whopping 6 times higher than the official 1.5% NPL level reported by China’s banking regulator!

So if one very conservatively assumes that loans are about half of China’s total asset base of $35 trillion (realistically 60-70%), and applies an 8% NPL to this number instead of the official 1.5% NPL estimate, the capital shortfall is a staggering $1.1 trillion.

Our conclusion back in 2015 was that “while China has been injecting incremental liquidity into the system and stubbornly getting no results for it leading experts everywhere to wonder just where all this money is going, the real reason for the lack of a credit impulse is that banks have been quietly soaking up the funds not to lend them out, but to plug a gargantuan, $1 trillion, solvency shortfall which amounts to 10% of China’s GDP!”

Since then, China’s bad debt fears took a back stage to even bigger Chinese problems, including capital flight, a slowing economy, a sharp decline in the country’s FX reserves, and most recently, a bitter trade war with the US which has crippled China’s manufacturing sector.

But, sadly, that did not mean that China’s bad debt problem had gone away; to the contrary, as Bloomberg reports, “China’s biggest banks are seeing bad loans grow at the fastest pace since at least 2017, as the country’s economic slowdown leaves its mark on the financial sector.“

While reporting generally strong Q1 earnings, China’s four largest lenders said in recent days that non-performing loans hit fresh multi-year highs in the latest quarter, reflecting risks to China’s banks as the government pushes them to lend more.

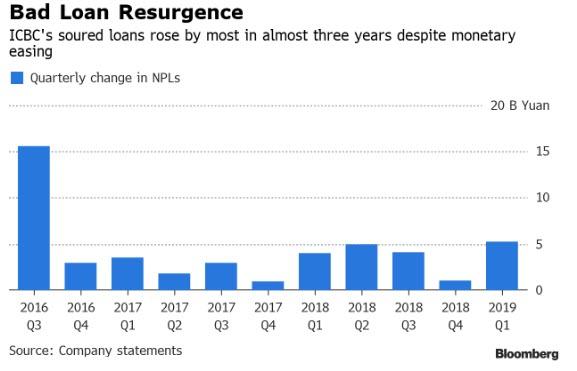

ICBC reported a 5.2 billion yuan ($770 million) rise in non-performing loans in the first three months, the biggest quarterly increase in almost three years. Bank of China saw its bad loans rise by 6.1 billion yuan – the most in three years – to the highest level since at least 2006. At Agricultural Bank of China Ltd., bad debt rose by 2.7 billion yuan, the biggest increase since the first quarter of 2017. China Construction Bank Corp.’s soured credit increased by 6.6 billion yuan, the most since 2016.

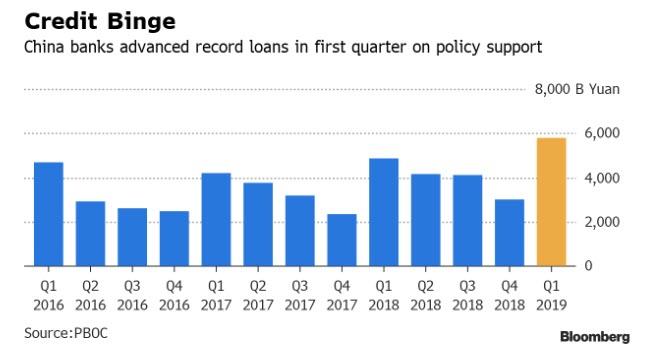

Even more striking: the surge in bed debt comes just as China made its biggest new credit injection ever in the first quarter, flooding the economy with 40% more total credit in 2019 compared to a year ago, and has once again saddled the local banks with even louder ticking timebombs on their balance sheets.

And while Bloomberg speculated that the increase in delinquent debt may give policy makers pause, we doubt it: after all prevailing consensus now is that China in coordinate with global central banks has launched a Second Shanghai Accord, and will not stop before the aggregate level of global inflation is comfortably high to delay the inevitable next recession by at least a few more quarters. Still, while China’s banks are seen as key to reinvigorating the economy, especially by lending to traditionally riskier smaller and private companies, some have expressed concerns that soured loans could continue to rise.

“Pressure to lend to small and micro-enterprises may gradually start to appear in bank’s NPLs,” said Shujin Chen, CFO of Huatai Secuirites. Weaker economic conditions will also impact bad loans though as a share of total lending it may remain little changed, she said.

The problem is only going to get worse: 45% of 202 bankers surveyed by China Orient Asset Management, one of four state-owned bad-debt managers, expect the nation’s bad-loan ratio to peak next year, according to the annual survey published in April.

The good news is that, for now at least, this growing bad debt problem has yet to appear in the income statement: despite concerns around bad loans, total earnings at the five biggest lenders, which control more than a third of China’s banking assets, are this year estimated to grow at the fastest pace in five years. “Banking stocks are likely to deliver both absolute and relative returns in the phase of monetary and credit easing,” China International Capital Corp. analysts led by Victor Wang said in an April 22 note to clients.

Others aren’t quite so sanguine, and as Bloomberg analyst Francis Chan writes, “ICBC and BoCom loan provisions could offset mild revenue gains, restricting earnings growth to mid-single digits in 2019. CCB may need to raise credit costs later this year. BoC earnings may get a short-term boost from robust sector loan growth, yet with full-year profit gains staying in the mid-single digits.”

Investors are similarly skeptical, as shares of China-listed banks have gained “only” 19% this year, underperforming the 23% increase in the Shanghai Composite. Among their concerns: increased lending to smaller businesses may hurt their asset quality and profitability in the longer term, and some analysts predict a turn in monetary policy to avoid over-stimulating the economy.

The big question, of course, is what Beijing will do with this data. Two Fridays ago, China’s Politburo said that the economy was better than expected in the first quarter, fueling concern that the government will dial back economic support measures. If China has indeed pulled its foot of the gas pedal, and the level of stimulus is about to drop off a (record) cliff, it’s time to quietly exit stage left, or as we put it last Sunday, just before the worst week for Chinese stocks in 2019, “If your bullish thesis to buy stocks in recent months has been anchored by the expectation of aggressive monetary easing by China reinforcing the narrative that “bad news is good news” for the market, you may consider selling.”

The Chinese did just that.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2GRIHxS Tyler Durden