Authored by John Rubino via DollarCollapse.com,

So the U.S. puts Republicans (the party of small government) in charge, and gets… trillion dollar deficits as far as the eye can see AND a revival of socialism among Democrats.

Scary as this may seem, the real (and even scarier) lesson is that it’s all inevitable: Beyond a certain level of indebtedness, even pro-business, sound money, small government leaders are powerless to stop the march to insolvency and currency crisis.

The latest example is Argentina, which a few years ago elected a free-market president, only to see its debt explode and its currency crash. From Friday’s Wall Street Journal:

Argentine President’s Prospects Dim With Those of His Country’s Economy

Argentina’s assets took a beating Thursday amid President Mauricio Macri’s continuing struggle to tame rising prices and revive a shrinking economy, raising prospects that his left-wing predecessor could make a comeback in this year’s presidential election.

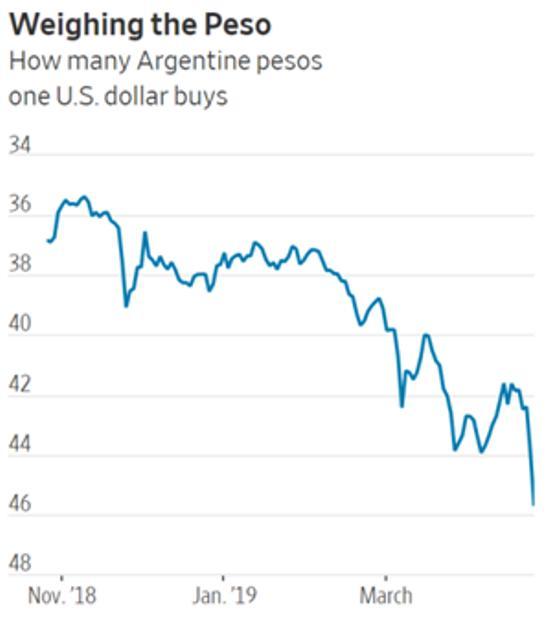

The peso lost more than 5% of its value against the dollar in early trading Thursday, before regaining some ground in the afternoon. Argentina is now the world’s second-riskiest borrower after crisis-hit Venezuela as indicated by credit default swaps, which are derivatives that pay holders when a borrower defaults on a debt payment.

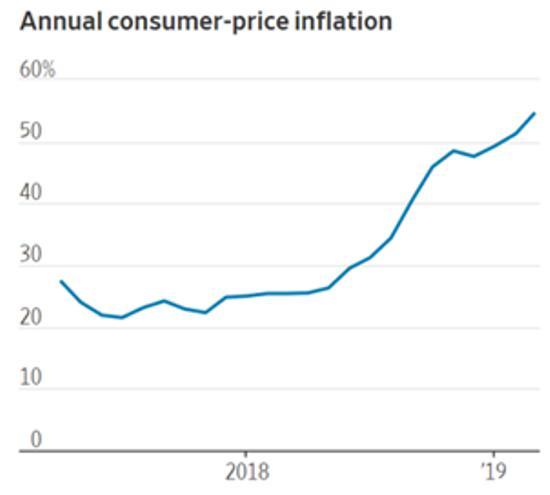

Mr. Macri, who was elected in 2015 on promises to undo the interventionist policies of President Cristina Kirchner, announced new price controls last week to try to get Argentina’s inflation under control. Mr. Macri has failed during his administration to contain inflation, which has risen to a 12-month pace of almost 55% in March from 25% at the start of 2018.

The move sparked criticism that the president was abandoning market-friendly policies for short-term electoral considerations as Argentines grow increasingly impatient with rising prices. It also underscored the possibility that Mr. Macri could lose October’s election, even if he faces the polarizing Mrs. Kirchner in the final runoff between the top two finishers of an initial vote. That scenario was considered unlikely just a few months ago.

“Both the recession and inflation have gotten so bad that not even facing Cristina Kirchner would be enough for [Mr. Macri] to win in the second round,” said Bruno Binetti, a political analyst at the Torcuato Di Tella University in Buenos Aires. “People are so displeased with the state of the economy right now that they would be willing to vote for her given their anger to the current government.”

Mr. Macri has said chronic budget deficits have boosted inflation and caused other economic difficulties. He has defended his government’s actions to balance his administration’s budget.

“We’re going to the source of the problem,” he said in a radio interview Wednesday. “It will take time,“ but inflation has to come down, he added.

The president’s unsuccessful efforts to end a recession that has pushed unemployment up to 9.1% and left about 30% of the country’s population living in poverty have caused a backlash among Argentines. A recent poll by Synopsis Consultores, a local consulting firm, showed Mrs. Kirchner with 45% support versus 44.3% for Mr. Macri in a runoff. Other polls show Mrs. Kirchner winning by a bigger margin.

“If the economy does not improve, the government falls in the polls. If the poll numbers fall for the government, then you have more pressure on the exchange rate, on the financial markets, and then that feeds into the real economy,” said Matías Carugati, head economist at Buenos Aires-based pollster Management & Fit.

“Macri is a disaster,” said Liliana Mejía, a 28-year-old student in Buenos Aires. “They all have to go.” She said she was upset that rising costs left her unable to buy a gift for her son’s second birthday next week.

But many Argentines still back the president, arguing that he inherited the problem after more than a decade of misrule by Mrs. Kirchner and her late husband, Néstor Kirchner.

“Cristina is to blame for all of this,” said Carlos Mayo, a 70-year-old retiree. “You can’t fix in two years the disaster that they did in 12 years.”

Mrs. Kirchner’s administration nationalized businesses and raised taxes on Argentina’s vital grain exports. She financed the deficit by printing money, imposed price controls on hundreds of consumer products and defaulted on the debt. She is facing trial on several corruption allegations, while denying wrongdoing.

Upon taking office almost four years ago, Mr. Macri moved quickly to eliminate most farm export taxes and lift foreign-exchange and capital controls in a bid to restore confidence among businesses, investors and consumers. He cut personal income taxes and invited foreign businesses to invest in Argentina’s energy and transportation sectors.

Mr. Macri, the scion of a wealthy Buenos Aires family, also provided the legal framework to attract foreign investment, said Juan Pereira, an analyst at Inframation, a global infrastructure and energy news and data service.

Mr. Macri borrowed heavily in global markets as he tried to slowly restore the government’s finances. He sought in that way to avoid the deep spending cuts and ensuing social unrest that led to the removal of past presidents during previous economic shocks.

But Mr. Macri found himself mired in a currency crisis after his government eased inflation targets at the end of 2017—an action some market participants saw as threatening the independence of Argentina’s central bank—and interest rates rose in the U.S. early last year. Mr. Macri turned to the International Monetary Fund for a bailout to calm investor concerns about debt payments.

The peso continued to weaken even after the bailout last June, and Mr. Macri had to return to the IMF in September to ask for more money as he promised to balance his budget by slashing government spending and raising taxes on farm exports.

Now, some investors are concerned that the government could eventually default on its debt, said Asha Mehta, a portfolio manager of Boston-based Acadian Asset Management.

“The main risks we see are the potential for a default, the IMF not offering further support, and the currency collapsing,” she said.

Investors are still willing to back Mr. Macri, according to Dominic Bokor-Ingram, a portfolio manager at London-based fund manager Fiera Capital.

“The preference in the international community is for Macri,” he said. “He didn’t have the political power to force through enough reforms, but if he were to get another four-year term there’s a very strong chance he’d be able to carry out the reforms he promised.”

Here’s the key sentence:

“Mr. Macri borrowed heavily in global markets as he tried to slowly restore the government’s finances. He sought in that way to avoid the deep spending cuts and ensuing social unrest that led to the removal of past presidents during previous economic shocks.”

When a country’s debts reach a certain point, “austerity” — that is, lowering spending to shrink deficits — causes so much pain to a population that has become addicted to easy credit and generous benefits, that the politician implementing it is kicked out and replaced with whoever promises the most free stuff. And the debt binge continues.

Europe found this out after trying to force peripheral EU countries to meet low deficit targets. The result is populists and/or socialists in charge of most of the biggest debtor countries.

Macri seems to have recognized the risk of austerity but discovered that borrowing more money to avoid spending cuts is simply business as usual under a different name.

Meanwhile, here in the US, from a financial standpoint it hardly matters who’s in charge after 2020 because massive spending increases are now the consensus, with the only argument being over which things we buy with all that borrowed money.

Put another way, Argentina is now the future of the developed world.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2PATYVW Tyler Durden