When Trump escalated the latest round of trade war with China by hiking tariffs on $200BN in Chinese exports to 25%, he had three things in mind: the US economy was firing on all cylinders (Q1 GDP had just printed above 3% even if the number was largely the result of one-time items), the S&P was at new all time highs, and most importantly, the Fed’s rate hikes had been put on indefinite hiatus. In fact, one can argue that a key reason why Trump decided to engage China in trade talks during the Q4 2018 crash, is because the Fed was still engaging in tightening, but five months later, Powell had been sworn to “patience”, which meant that Trump would only have to worry about the trade war’s impact on stocks, while ignoring the potentially destabilizing influence of the Fed.

In fact, one can take the argument further, and asset that as stocks tumbled as a result of trade war, Trump could add even more pressure on Powell to cut rates or launch QE as he has repeatedly urged the central bank to do.

Which brings us to the latest round of trade war, which promises to be a long one: as Deutsche Bank’s Jim Reid writes, “the stakes have been raised enough for it to be tough for either side to back down imminently so one wouldn’t expect the news flow to rapidly improve in the near term. It doesn’t help that the Chinese economy has stabilised and that the S&P 500 is back close to record highs even with a small sell off last week. So there is no immediate need for anyone to backtrack. As such, markets will likely struggle for a while although last week they did try to rally back a few times as softer trade headlines and rhetoric brought us back from larger falls.”

So in an ideal world, the US would appear able to weather an extended trade war with China, at least until stocks dropped low enough to trigger the “Trump put.” Yet despite the favorable optics, has Trump miscalculated? The answer depend on what Chinese exports are included in the upcoming expansion of tariffs.

That is also the key question of Zhiwei Zheng, DB’s China Economist, ’who asks whether the US will move to impose tariffs on the remaining around $300bn of Chinese exports (Lighthizer overnight suggests we’ll learn more on this later).

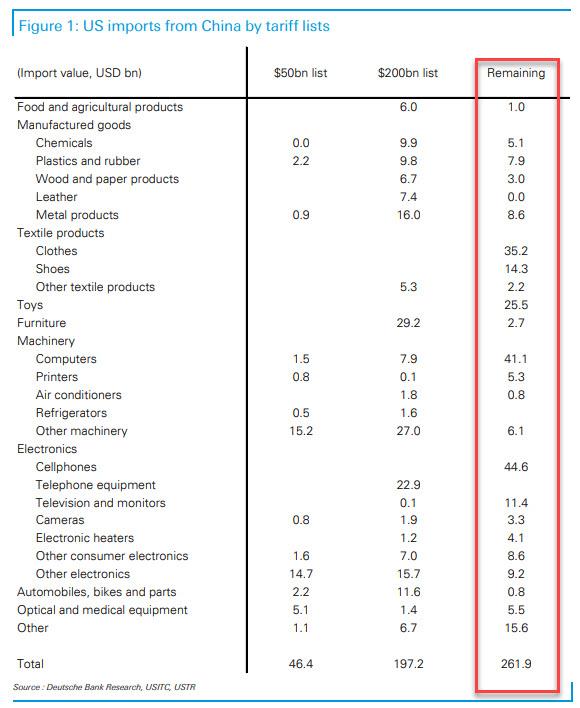

And this is where Trump may be making a mistake, because as Deutsche Bank explains, the remaining Chinese exports are significantly different from the other Chinese exports, as they include mostly consumer goods such as smartphones, computers, and textiles, and US consumers are more dependent on China for these goods. These are shown in the red box below:

So, as the German bank concludes, “there are ways this could get more painful, especially as these goods are well integrated into the global supply chain.“

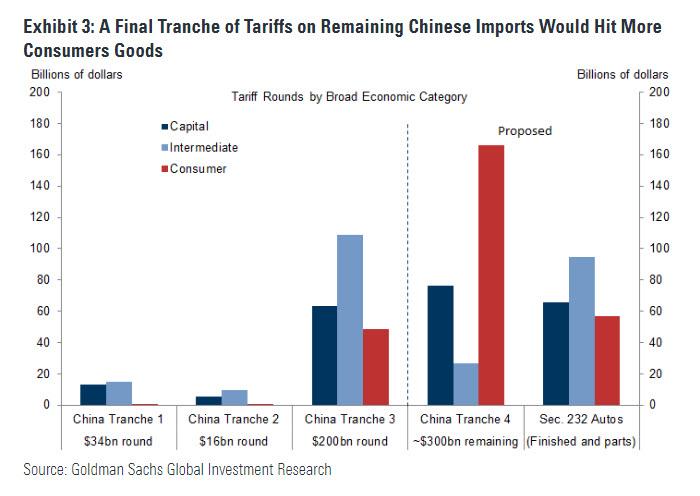

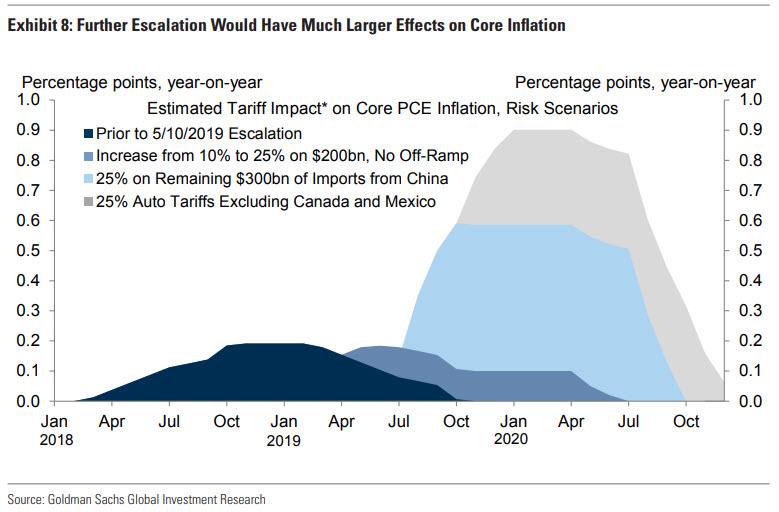

It’s not just Deutsche Bank though: as Goldman wrote in a Friday report, consumer goods account for only about 25% of the items targeted by the tariff rate increase on Friday and only about 15% of all imports subjected to new tariffs so far. But consumer goods account for about 60% of all remaining imports from China (see chart below), “implying much larger effects on inflation if the White House does eventually implement a final tranche of tariffs.”

Additionally, Goldman’s economists also note that imports from China account for a much larger share of total imports in the categories covered by Tranche 4 than in prior rounds. For example, computers, cell phones, and toys are some of the largest categories in Tranche 4, and China accounts for 80% or more of total US imports of each product group. This, according to Goldman chief economist Jan Hatzius, “could make it harder for US importers to source from other countries not affected by the new tariffs.”

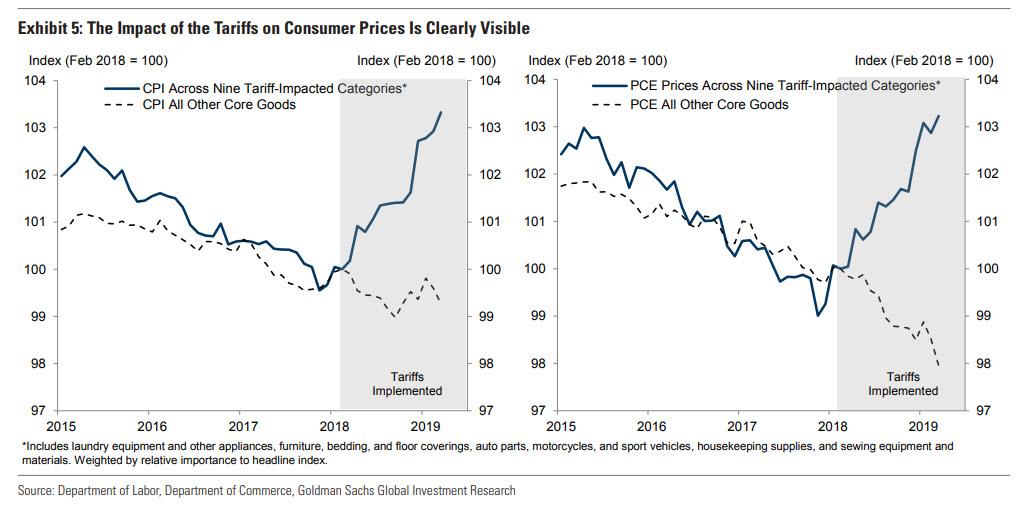

It’s not just what may happen in the future that has Goldman worried (even though it is extremely intuitive that higher tariffs would always result in higher prices and a jump in inflation): according to the bank, new evidence on the effects of the 2018 tariff rounds from two detailed academic studies points to larger effects on US consumer prices than the bank had previously estimated, for two reasons. First, the costs of US tariffs have fallen entirely on US businesses and households, with no clear reduction in the prices charged by Chinese exporters. Second, the effects of the tariffs have spilled over noticeably to the prices charged by US producers competing with tariff-affected goods.

In light of this new evidence, and this is the important part, Goldman said that it is revising up its estimates of the inflation effects of the tariffs to date. In a first approach, the bank updated its earlier accounting estimate of the direct effects of the tariffs to reflect the finding that none of the costs of the tariffs have fallen on Chinese exporters, suggesting a 0.08pp direct effect on core PCE inflation. Goldman also updated uts earlier estimates of spillovers based on industry-level PPI data, which now suggest an additional 0.10pp indirect effect for a total effect of 0.18pp. In a second approach, Hatzius estimates the impact by multiplying the trend break in the tariff-affected categories shown in Exhibit 5 by their weight in the core PCE index, resulting in a 0.20pp estimate. Averaging the two approaches suggests a 0.19pp boost to core PCE inflation at present, as shown in Exhibit 6.

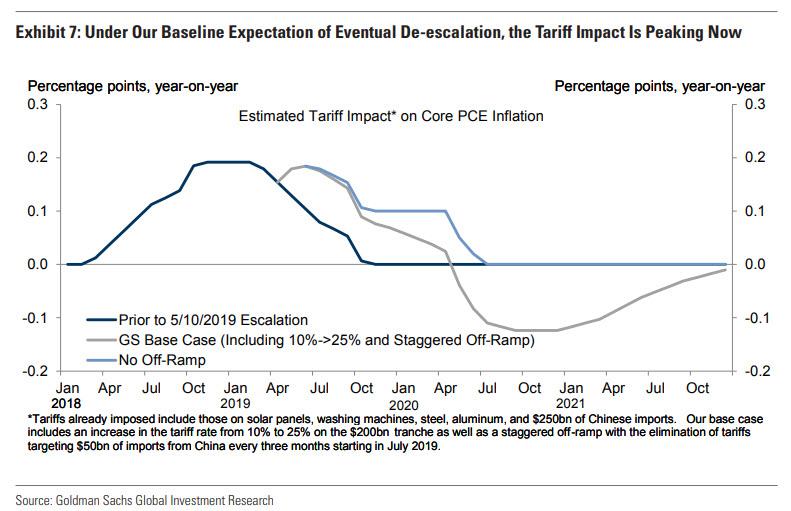

Goldman also revised its estimates of the tariff impact going forward under its policy baseline, and predicts that while the effects of earlier tariff rounds will begin to fade (Exhibit 7, dark blue line), the tariffs imposed yesterday should begin to provide a boost in June that will eventually amount to 0.1pp, keeping the total tariff impact close to 0.2pp until a deal is struck.

The total impact would then fade as tariffs begin to decline in a staggered off-ramp (grey line). Goldman assumes tariff reductions would lower prices eventually but at only half the speed at which tariff increases raised prices, resulting in only mild disinflationary peak effects in mid-2020 as de-escalation continues.

All of the above assumes the status quo continues.

If, instead, the trade war escalates further from here, the inflation impact could become quite large, and Goldman calculates that imposing 25% tariffs on roughly $300bn of remaining Chinese imports would have a peak effect of 0.5pp on core PCE, while auto tariffs would have a roughly 0.3pp peak effect. These considerably larger effects reflect the much larger share of consumer goods that would be affected. If all proposed tariffs were implemented within a year, the total impact on core PCE would peak at around 0.9pp.

It doesn’t stop there, because larger effects of tariffs on prices also imply a larger hit to real income and consequently to GDP. And while Goldman’s estimate of the growth impact in its baseline scenario remains fairly modest, with a peak drag on the level of GDP of 0.1-0.2% by end-2019, the unspoken risk here is clear: stagflation. Indeed, further escalation of the trade war could result in a hit to GDP as large as 0.4%, and if trade tensions sparked a major sell-off in the equity market the growth impact could worsen considerably.

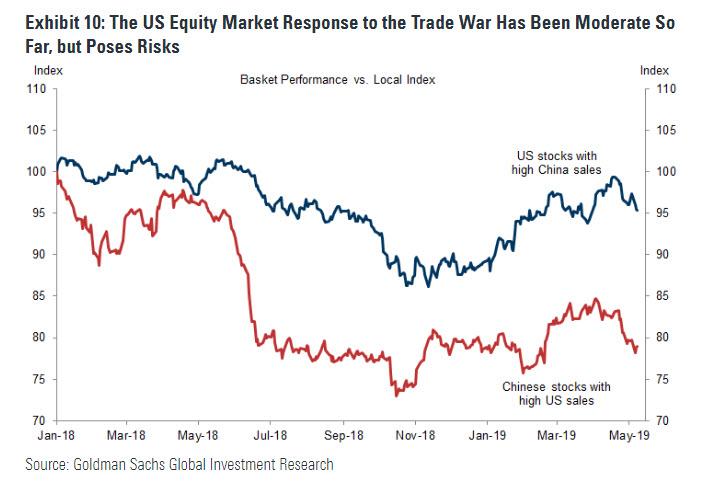

Another potential risk is an amplification of the direct economic impact by a major deterioration in risk sentiment, i.e., a market selloff. Here, Goldman notes that the level of anxiety about the trade war in US financial markets has varied over time as US stocks with significant China sales generally underperformed, but only moderately. The broader market reaction to trade war news was quite strong in the early stages, but then faded later in 2018 before showing signs of life again this week. In short, while the market reaction to further escalation is hard to predict, a larger sell-off is a potential risk. A 10% decline in equity prices, for example, would roughly double the peak hit to the level of GDP in the risk scenario to about 0.8%.

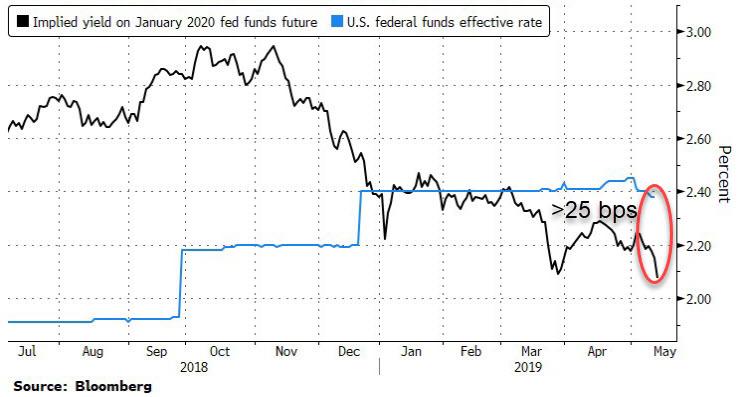

But the biggest risk from sharply higher inflation is not to the economy, it is to markets because Powell’s self-declared “pause” will end very soon if inflation were to spike. Goldman agrees, noting that while the implications for the Fed are substantial even under the policy baseline – as re-escalation of the tariff war has revived one of the downside risks to growth that Chair Powell noted only last week seemed to be fading, but also means that the inflation boost is likely to persist somewhat longer – the bigger risk is the impact of further escalation, which according to Goldman “would raise the odds of core inflation rising noticeably above 2% next year.” And while temporary, this will notably increase the likelihood of a rate hike that the FOMC thought was warranted by the broader outlook.

In short, instead of raising odds of a rate cut, something the market has aggressively priced in, and as we noted earlier today, the market now anticipates at least one rate cut by the Fed before the end of 2019…

… the escalating tariffs, and a potential new round of tariffs, one which affects the remaining $300 billion in Chinese imports, could backfire in Trump’s fact with stocks not only sliding on global growth fears, but due to fears that the coming stagflation will prevent Powell from cutting, in fact, it may force the Fed to hike rates at least one more time, a development which would send the S&P plunging now that more than one cut is already priced in.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2VlCYEv Tyler Durden