Authored by Nick Cunningham via OilPrice.com,

U.S. oil production continues to grow, but the shale industry is in the midst of a deceleration as low oil prices and a financial squeeze slow the pace of drilling.

The U.S. added 246,000 bpd of fresh supply in April, the latest month for which data solid is available. That put to rest concerns that the industry was in the midst of contraction, after production fell in January and February (some of which was due to offshore maintenance). Even as the rig count continues to fall, production grinds higher.

The EIA expects output to grow by another 70,000 bpd in July, with the Permian alone adding 55,000 bpd.

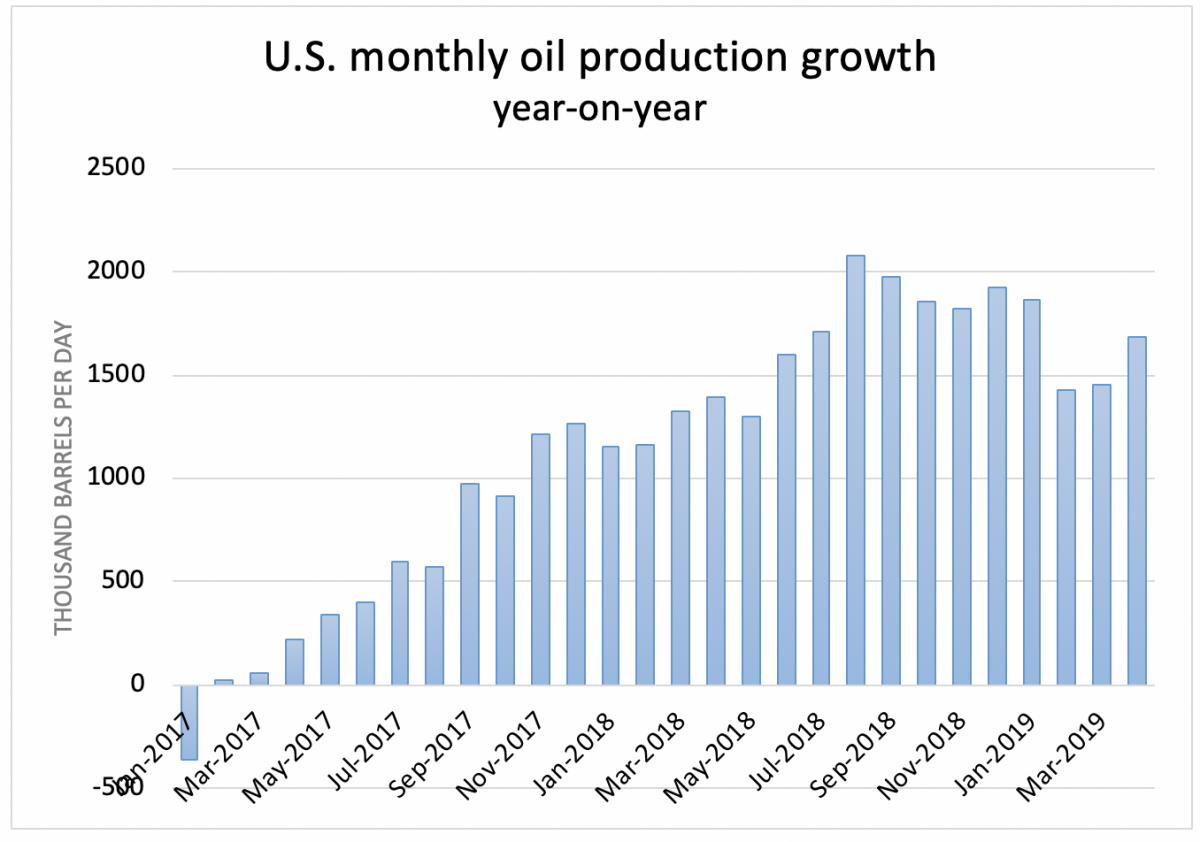

But the rate of growth is slowing. In April, production was up 1.6 million barrels per day (mb/d) compared to the same month a year earlier. By any measure, that is a massive increase. But it is down sharply from the nearly 2.1 mb/d year-on-year increase seen in August 2018, which looks set to be the peak in terms of the pace of growth.

(Click to enlarge)

U.S. oil production is not in danger of outright decline, not for the foreseeable future. But growth is clearly slowing. The U.S. could add 1.3 mb/d of new supply this year, according to an average of forecasts from multiple analysts, compiled by Reuters. That figure would be down from 1.5 mb/d of additional supply that came online in 2018.

Financial stress is spreading, and top industry executives in Texas are arguably at their gloomiest in years. Consolidation and bankruptcies could pick up pace in the next few months, a bankruptcy attorney told Reuters.

Investors have soured on shale drillers, closing the door on fresh capital injections. The “biggest impact has been the rapid and accelerating lack of investor interest in both conventional and unconventional oil and gas. The securities of oil and gas companies now sell at a fraction of what they once commanded. Huge losses in these shares hamper new exploration. It looks like another round of bankruptcies and mergers,” one oil executive said in a survey by the Dallas Federal Reserve in June. Most shale drillers are still not profitable.

But it isn’t just access to finance and unimpressive returns that raise concerns. Another major headwind looms for the industry. To the extent that energy executives could make a compelling case to investors, much of it came down to the notion that costs decline over time, drilling techniques continue to improve, and companies could steadily increase the volume of oil and gas that they recover from individual wells. All of that added up to lower breakeven costs, more production, and – hopefully – profits somewhere down the line. This mantra kept skeptical investors on board, greenlighting the next tranche of capital that was injected into the ground.

However, the tweaking of drilling techniques is not registering progress in the same way that the industry experienced in years past. Nor is the progress consistent with what companies have promised.

The Wall Street Journal published another blockbuster analysis on July 4, looking at failed promises of packing wells ever-closer together. The intensification of drilling from a single location, with dozens of wells drilled at varying depths, was thought to lower costs and boost output. But one high-profile test case has proved to be a disappointment.

According to the WSJ, Encana’s “cube development,” which saw 33 wells drilled from one location, “is on track to pump about 300,000 barrels of oil over 30 years,” which is “about half the amount of oil Encana said a typical well would pump in late 2017.” It’s also half the 60 or so wells the company originally planned to drill.

The problem is the “parent-child” well interference problem, an issue that has cropped up over the past few years as companies intensify drilling operations.

The results from Encana’s test offer further evidence that shale drillers will ultimately not be able to produce as much oil as they have said they can. Encana had stacked wells as close as 330 feet apart, with poor results. They forced them to begin spreading the wells out again, reverting back to 500 feet of space between wells, according to the WSJ.

That may not seem like a significant problem, but because it surely applies to all drillers, and not just Encana, the potential of U.S. shale might be less impressive than most people believe. As the WSJ put it, U.S. production “could peak far sooner than expected.”

In the interim, the larger companies that have the acreage, capital and technology to play around with different techniques and spacing are the ones that can weather the storm. Smaller companies, which have an immediate need for capital to drill their next well, are facing a much deeper problem.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2YKDIFA Tyler Durden