Now that trade war with China has escalated substantially yet again following a weekend in which both the US and China hiked the tariff rate on billions of imports, Deutsche Bank is revisiting how China’s stance towards the trade war has evolved over the past 1½ years, and how it may change in the future.

As a reminder, while China first sought to prevent a trade war, and then tried to quickly reach a trade deal with the US, DB economist Yi Xiong notes that China’s strategy has changed again since early May, and he describes China’s current strategy as “endurance”: the main goal is to preserve China’s economic resilience, while taking the higher US tariffs as a given fact.

The premise for China’s new strategy is two-fold:

- frictions between the US and China have gone far beyond trade, reducing China’s potential gains in a trade deal; and

- damage from the higher US tariffs to China’s economy has been manageable.

Under this strategy, we think China will continue trade negotiations despite the new tariffs, but it is not willing to meet all US demands to reach a deal quickly. When the US increases tariffs, China will respond with smaller and targeted tariffs on specific products. China will also accelerate its opening up to other countries and diversify its supply chains. But it will not proactively cut off economic ties with the US.

Domestically, China will not excessively stimulate the economy to counter short-term trade shocks, and will exercise extreme caution to prevent asset bubbles, especially in housing.

As even Trump has realized by now, China’s current strategy likely has a long time horizon embedded in it – one at least as long as the next presidential election, although the time horizon may go beyond the life cycle of the current US administration. As China sees it, political dynamics in Washington DC imply that the US’s attitude toward China is unlikely to change course, no matter which party is in power. A reference point would be the US-Japan trade war, which lasted more than a decade.

The future course of the trade war will, therefore, largely depend on the US’s trade war strategy. DB’s baseline scenario is for prolonged trade tensions with some back and forth. Tensions may escalate at times, while trade talks and perhaps partial agreements may help ease tensions at other times. We think the likelihood of a comprehensive trade deal is small. The main downside risk to this baseline is if US-China tensions escalate substantially on non- economic fronts – security, geopolitical, or China’s sovereignty issues – this could derail the trade talks leading to a full-blown trade and economic war.

Trade war: where are we now?

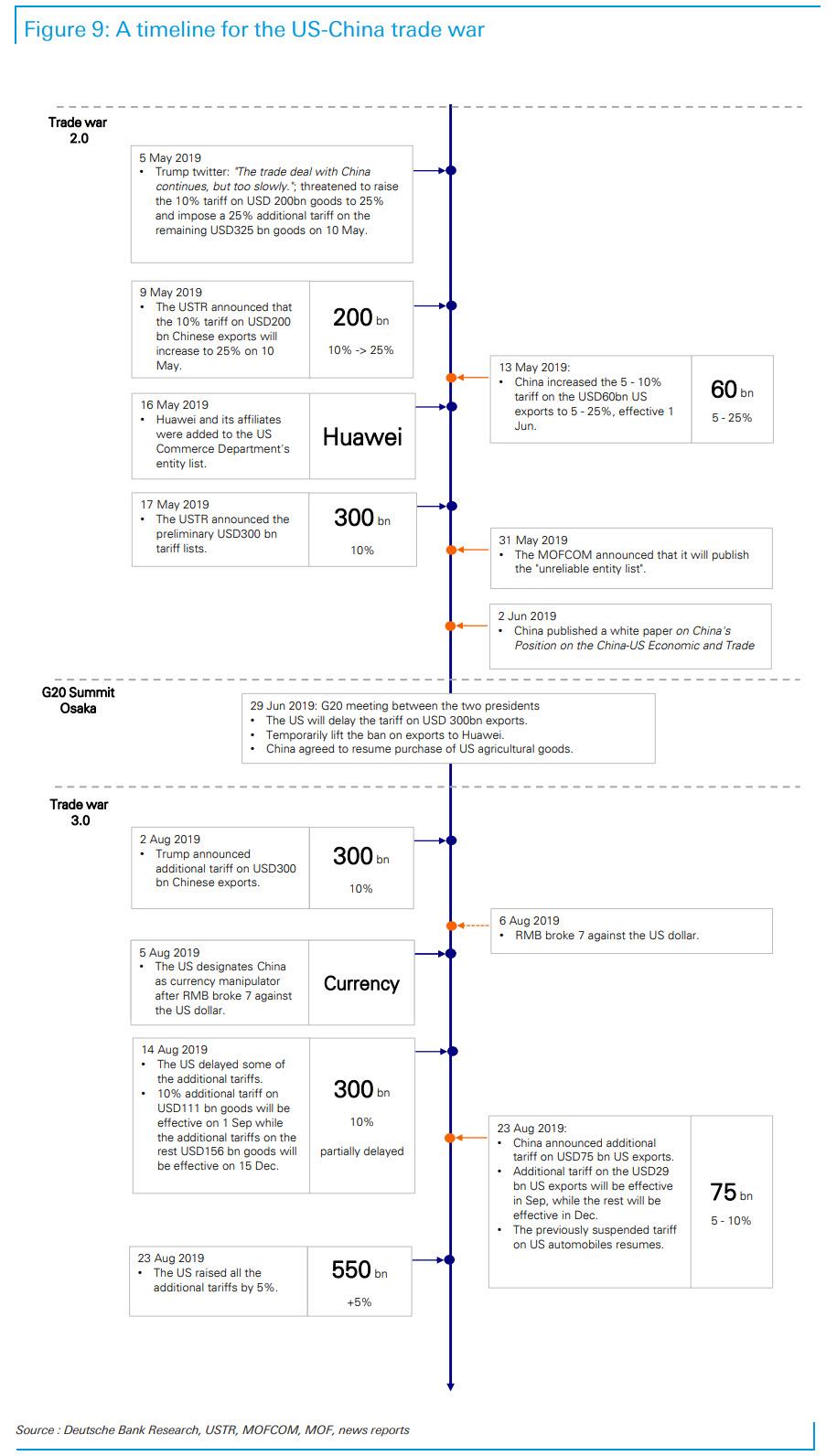

It feels like a long time ago, but it’s been only two months since Presidents Trump and Xi reached an agreement at the G20 summit to put a halt to the trade war. Throughout July, some limited progress was made on both lifting the Huawei ban and increasing China’s agricultural purchases. Tensions quickly re-escalated in the first week of August, when Trump announced that he would put a 10% tariff on US$300bn of Chinese goods. China swiftly vowed that it would retaliate, and put further purchases of US agricultural goods on hold. The RMB depreciated in the next few days, breaking the 7 threshold against the USD, and the US responded by declaring China a currency manipulator. Tensions eased slightly as the negotiation teams talked over the phone, and on Aug 14 the US delayed tariffs on more than half of the USD300bn list to mid-December.

This brings us to a flurry of events that unfolded over the past weekend:

- On Aug 23, Friday evening Beijing time, China published its new tariff list. It will impose 5% to 10% addition tariffs on USD75bn of US goods, in retaliation to the US’s USD300bn tariff list. It will also resume the previously suspended 25% tariff on autos.

- President Trump quickly countered that he would respond to the new tariffs. One significant message from one of his tweets was: “who is our bigger enemy, Jay Powell or Chairman Xi?”

- After US market close, President Trump announced that he would raise tariff rates on the USD250bn list from 25% to 30%, and on the USD300bn list from 10% to 15%. This is effectively a 5% tariff raise on almost all Chinese exports to the US.

Tensions eased somewhat afterwards. On Saturday, China’s Ministry of Commerce warned the US to “bear all consequences”, but it did not explicitly say that China would announce retaliatory measures. On Monday, Chinese Vice Premier Liu He called for calm negotiations , while President Trump suggested “we’re having meaningful talks, much more meaningful than I would say at any time”.

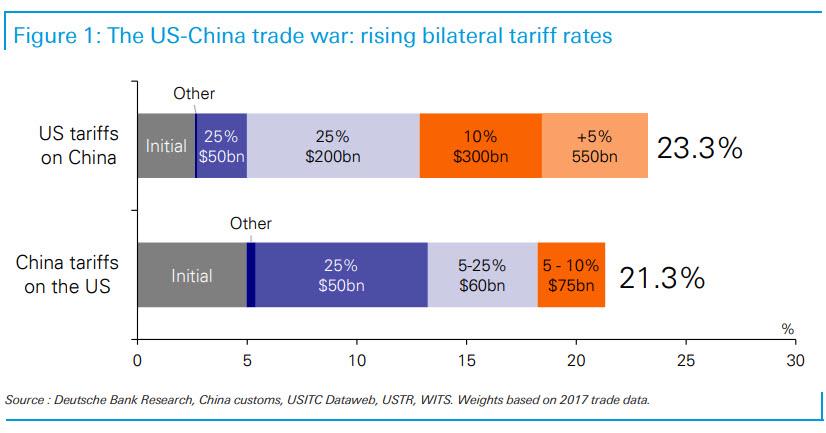

Despite the verbal de-escalation, the tariff increases from both sides did take place, as expected, on Sept 1 at midnight (China’s tariffs hitting 1 minute after the US). If all these new tariffs become effective, by Dec 2019 the US would have an average tariff rate of 23.2% on China. This would exceed China’s average tariff rate on the US, which would be 21.3% by Dec, absent further measures.

China’s evolving trade war strategy

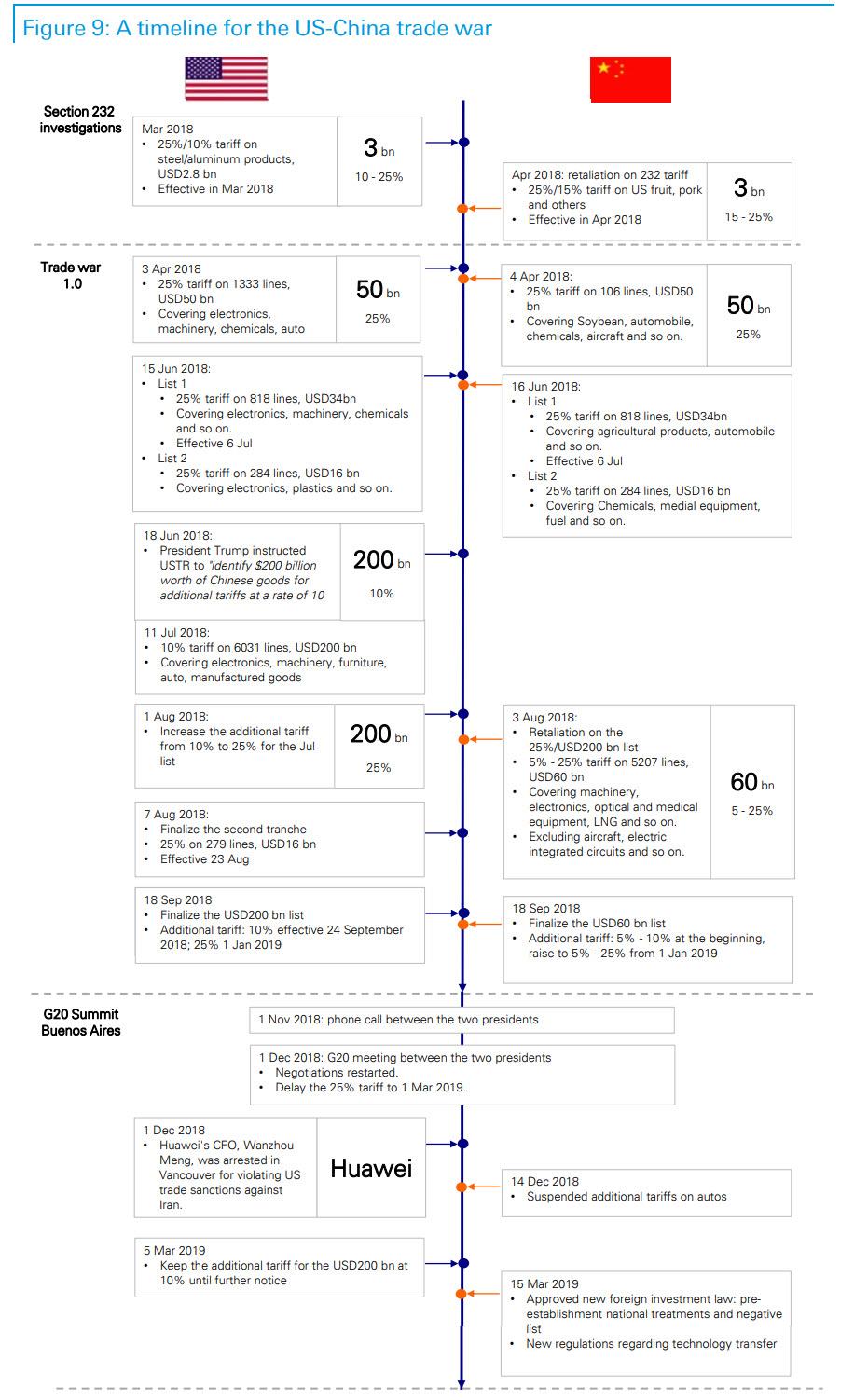

China’s responses to the recent few rounds of US tariffs since May are somewhat different from its previous responses, and Deutsche Bank thinks they reflect a change in China’s strategy. To understand China’s current stance, it is helpful to review what has happened since the trade war began (see trade war timeline below) to see how it has changed over time. In simple terms, China’s strategy in the past 1½ years can be divided into three stages:

- Stage 1: Deterrence (early 2018 – Sep 2018). In the first phase of the trade war, China’s strategy was perhaps best described as trying to deter the US from imposing tariffs. Recall that in the beginning, a full-fledged trade war was viewed as a tail risk by most observers. For each round of US tariffs over this period (the 232 list, the USD50bn list, and the USD200bn list), China responded immediately with comparable tariffs on US goods. It can be described as a “game of chicken” strategy: in order to prevent the trade war, China must prove its willingness to match all US tariff threats, so as to convince the US that both sides would have a lot to lose. When the trade war became reality, the RMB depreciated rapidly from around 6.3/USD in Mar 2018 to 6.9/USD in Sep 2018.

- Stage 2: Compromise (Nov 2018 – Apr 2019). Presidents Trump and Xi’s phone call in early Nov 2018 marked the start of the second phase, which lasted until April 2019. After earlier moves failed to prevent a trade war from happening, we think China showed genuine willingness to make a deal to prevent further deterioration in the US-China relationship. Over this period, China held frequent (6 rounds) trade talks with the US, purchased US agricultural products, suspended tariffs on US autos, passed a new Foreign Investment Law, and revised regulations on technology transfers. The RMB was stable, appreciating to 6.7/USD by April.

- Stage 3: Endurance (May 2019 – now). Recent developments suggest that the trade war likely entered a new phase. It started when the trade talks broke down in May. A symbolic event is that China issued a white paper on its position in trade talks in early June. In the white paper, China laid out a series of principles for a trade deal. The white paper formalized China’s positions, which had not been spelled out clearly before. The RMB depreciated again, reaching 7.1/USD in August.

There are two main reasons why China has changed its strategy lately. The primary reason for the change is that China no longer sees resolving the trade war as the top issue in US-China relations. Over the past year, frictions between the US and China have gone far beyond trade, including on the fronts of technology barriers, security, geopolitical issues, and even China’s sovereignty issues. If China had hoped before that resolving the trade war could help improve overall US-China relations, that hope is largely gone. The second reason is that China may have judged the damage of the trade war as manageable, based on evidence that we will discuss in the next section.

This latest strategy can be labeled as “endurance” because China no longer seems to seek a near-term solution to the trade war. Currently China is neither aiming to quickly reach a trade deal, nor trying to hit back at the US as hard as it can. Rather, China seems to have internalized the trade war as a given fact, and is trying to preserve China’s economic resilience under rising tariffs. In the words of the white paper, “China remains committed to its own cause no matter how the external environment changes”.

China’s current trade war strategy can be summarized as follows:

China is willing to continue trade talks… China has not yet canceled any trade talks with the US, despite all the new tariffs. Whether or not an agreement can be reached, China still judges having trade talks as better than no talks at all. Stopping the talks may send the wrong message that China does not want a trade deal at all: it does, but not at any cost.

- …but it will abide by the principles set in the white paper. Solving the tariff problem is unlikely to resolve the broader problems between the US and China. Even the Huawei ban, which is partly a trade issue, does not seem to be something the US can rescind in a trade deal. Therefore, China is not willing to offer a lot for a trade deal, given the limited benefits.

- China will still respond to US tariffs, but with smaller and targeted measures. As is shown in Figure 1, recent China retaliatory tariffs are smaller than corresponding US tariffs not only in absolute size, but also in relative terms. The goal of retaliation is not to maximize the damage to the US, but to disincentivize further US tariffs. For the same reason, China is likely reluctant to take non-trade actions against the US, such as punishing US business interests in China . In fact, it may be just the opposite: Costco just opened its first store in China, and Tesla’s Shanghai factory will be completed soon.

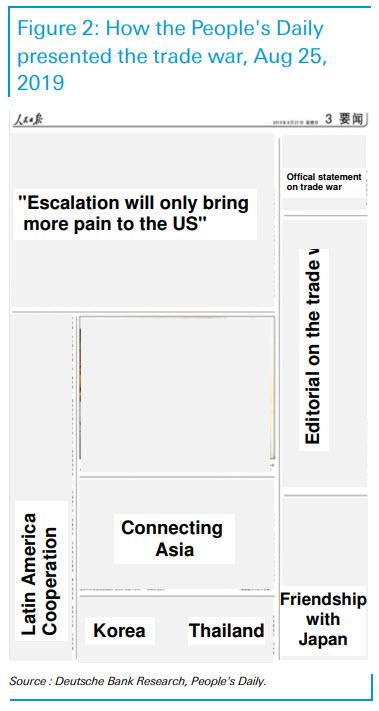

- China will also accelerate its opening up to other countries. This will both help the Chinese economy and increase the cost for the US in a trade war. In the longer term, China will likely reduce its supply chains’ reliance on the US. A page from Sunday’s People’s Daily (the official newspaper of the CPC) interestingly puts official statements and comments about new US tariffs on the same page as multiple articles about China’s improving cooperation with other countries (we provide the layout in Figure 2 ).

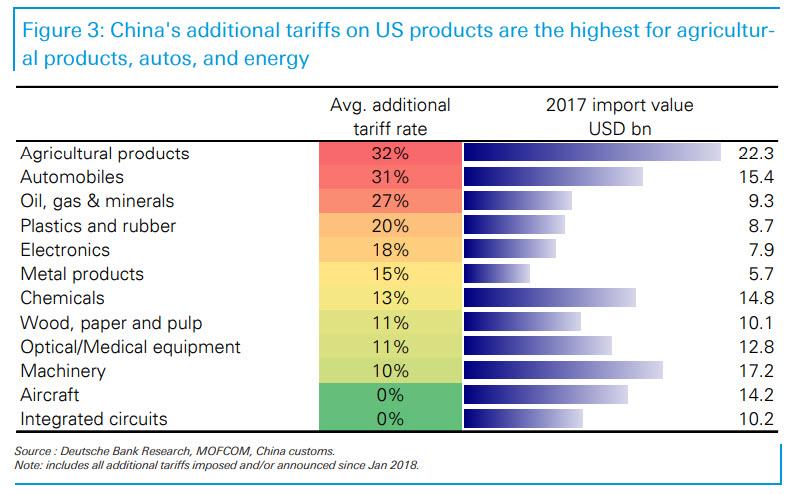

A case in point here is how China recently raised tariffs in retaliation to the US tariff on USD300bn of Chinese goods. China’s retaliation came out not only smaller in size (USD75bn compared to USD300bn) but also lower in tariff rates (5 – 10% compared to 10%). The new list substantially overlaps with China’s previous tariff lists: about 90% are items that have already been tariffed before. This is because the new list is well targeted at the product level. In fact, if we calculate China’s additional tariffs by product categories, it is clear that tariffs increased the most for agricultural products, automobiles, and energy, the products that the current US administration cares about the most. On the other end of the spectrum, tariffs increased the least for products such as ICs, machinery, and medical equipment.

An important assumption to China’s endurance strategy is that the trade war would not lead to a collapsing Chinese economy. On this front, China appears to be learning from Japan’s experience in the 1980s. Most economists and policymakers now believe that it was not the US-Japan trade war that ended Japan’s economic growth miracle. Japanese companies remained competitive internationally, despite the trade war. Rather, it was a series of policy mistakes that led to an unprecedented housing bubble and a prolonged balance sheet recession.

Based on this diagnosis, policymakers are likely not overly worried about the direct impact of the trade war. Meanwhile, they are extremely careful not to repeat Japan’s policy mistakes in the 1980s – 1990s. It will not excessively stimulate the economy to offset short-term trade shocks, and will exercise extreme caution to prevent asset bubbles, especially housing bubbles. Evidence so far seems to support this claim that the trade war is not very damaging. China’s growth has slowed a lot since early 2018, but the slowdown has been largely driven by domestic factors, including deleveraging policies, a fall in government investment, higher household debt burdens, and automobile replacement cycle, all of which have been covered previously. External demand also played a role, but the direct contribution of the trade war does not seem to be very large:

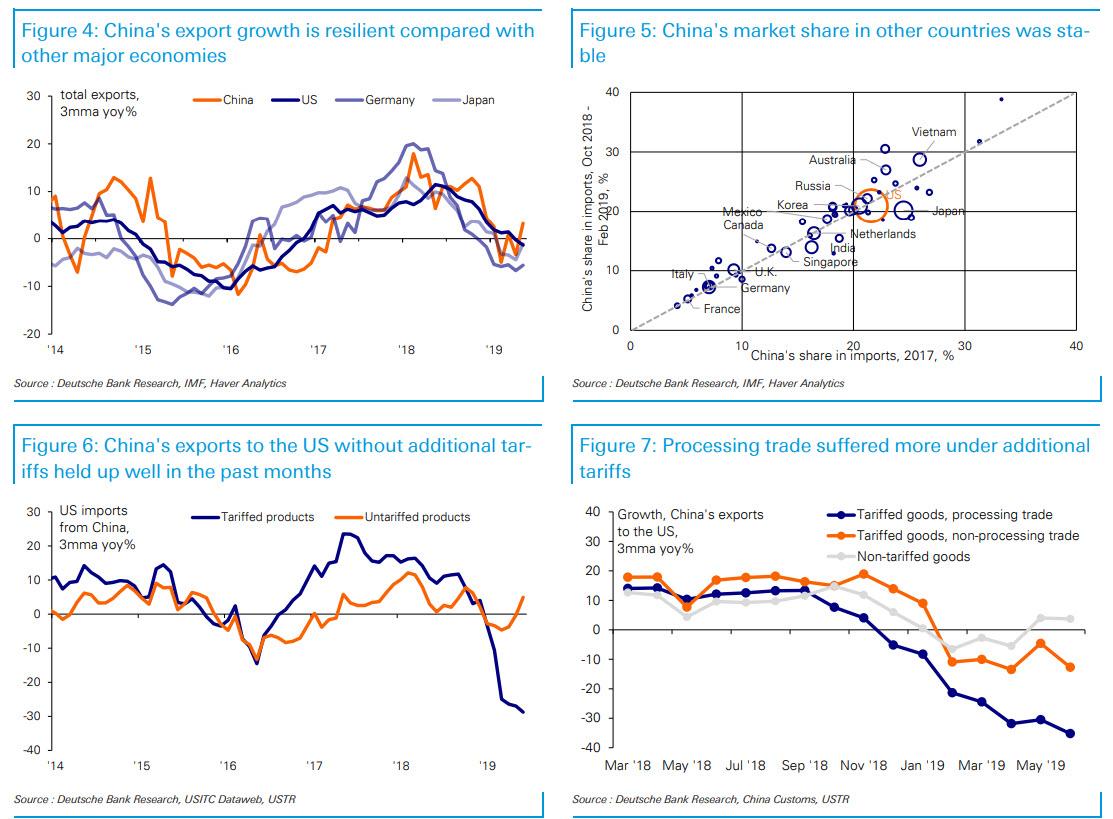

- China’s total exports growth stayed positive (+0.6% yoy) in the first 7 months of 2019. So far in 2019, China’s exports performance has in fact been better than most other major economies ( Figure 4 ).

- 80% of China’s exports are to countries other than the US. The trade war does not seem to have affected China’s competitiveness elsewhere: overall, China has not lost market share in these markets ( Figure 5 ).

- For the 20% of China’s exports that went to the US, exports did fall sharply. US imports from China fell -12% yoy in H1 2019, of which those subject to additional tariffs fell -27% yoy ( Figure 6 ). However, processing trade exports–whose domestic value added is usually small–have fallen more, while the decline in non-processing exports was mild ( Figure 7 ). This suggests the damage to China’s GDP may be much smaller than the drop in headline exports.

- Furthermore, studies have shown that so far the US importers and consumers have borne substantially all of the tariff increase. The US seems unable to pass on the tariff increases to Chinese exporters, though the exact reason is unclear. Maybe Asia’s dominance in manufacturing has given Chinese exporters more market power; or maybe it’s just too early as pricing behavior change takes time.

These results above have not taken into account the impact of the latest rounds of tariffs. The US average tariff rate on China will increase by another 10% between end-June and end-December, if all the announced measures become effective. However, this impact will be at least partially offset by China’s exchange rate flexibility.

Here, DB notes that its baseline RMB exchange rate forecast is at 7.1/USD by end-2019. This forecast does not take into account the most recent rounds of tariffs announced. The upcoming meeting between US and China teams in September will hopefully prevent or delay these new tariffs. If tariffs indeed all become effective, the RMB will face further depreciation pressures to likely 7.3/USD by end-year. Here analysts should think in terms of China’s entire exports to the world: China would face a 2% increase in weighted average tariff between June and December, if all US measures become effective. At 7.3/USD, the RMB would also depreciate by about 2% against the trade-weighted currency basket between June and December.

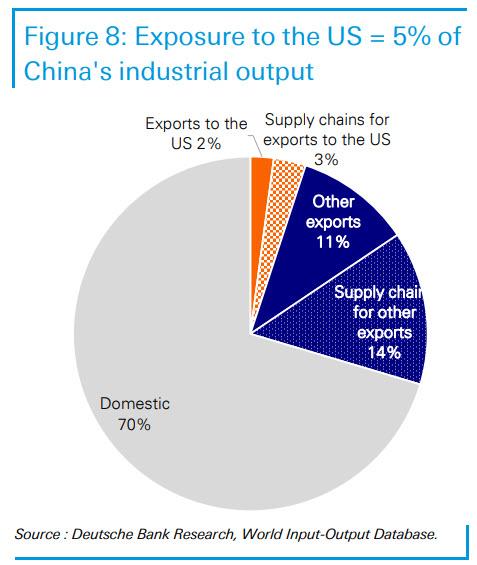

It is of course possible that the US may raise tariffs even further. The most extreme scenario for tariffs is that the US raises them across the board to prohibitive levels (50% or more), such that most Chinese goods are driven out of the US market. Using the World Input-Output Database, the impact, including on both the exporting industries and their upstream suppliers, would be a 5% loss of China’s aggregate industrial output, a 2% loss of GDP, and a 1.5% increase in the unemployment rate.

This would be painful to manage, but arguably is not calamitous for China. China could respond with a policy mix of more monetary easing and fiscal spending, flexible exchange rate, and further opening up to the rest of the world.

Conclusion

China’s stance towards the trade war has changed since early May, and Deutsche Bank describes China’s current strategy as “endurance”: the main goal is to preserve China’s economic resilience, while taking the higher US tariffs as a given fact. The premise for China’s new strategy is two-fold:

- frictions between the US and China have gone far beyond trade, reducing China’s potential gains in a trade deal; and

- damages of the higher US tariffs on China’s economy have been manageable.

Under this strategy, think China will continue trade negotiations despite the new tariffs, but it is not willing to meet all US demands to reach a deal quickly. When the US increases tariffs, China will respond with smaller and targeted tariffs on specific products. China will also accelerate its opening up to other countries and diversify its supply chains. But it will not proactively cut off the economic ties with the US. Domestically, China will not excessively stimulate the economy to counter short-term trade shocks, and will exercise extreme caution to prevent asset bubbles, especially in housing.

China’s current strategy likely has a long time horizon embedded in it. This is unlike China’s previous strategies, which had sought to prevent a trade war at first, and then to quickly reach a trade deal. The time horizon of the strategy may go beyond the life cycle of the current US administration. As China sees it, political dynamics in Washington DC imply that the US’s attitude toward China is unlikely to change course, no matter which party is in power. A reference point would be the US-Japan trade war, which lasted more than a decade.

The future course of the trade war will, therefore, largely depend on the US’s trade war strategy. The baseline scenario is for prolonged trade tensions with some back and forth. Tension may escalate at times, while trade talks and perhaps partial agreements may help ease the tension at other times. That said, the likelihood of a comprehensive trade deal is small, and the main downside risk to this baseline is if US-China tensions escalate substantially on non-economic fronts – security, geopolitical, or China’s sovereignty issues – this could derail the trade talks leading to a full-blown trade and economic war.

Appendix:

A Time of the US-China Trade War

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2PGl7dJ Tyler Durden