Which Banks Were Behind The “Repocalypse” Funding Squeeze?

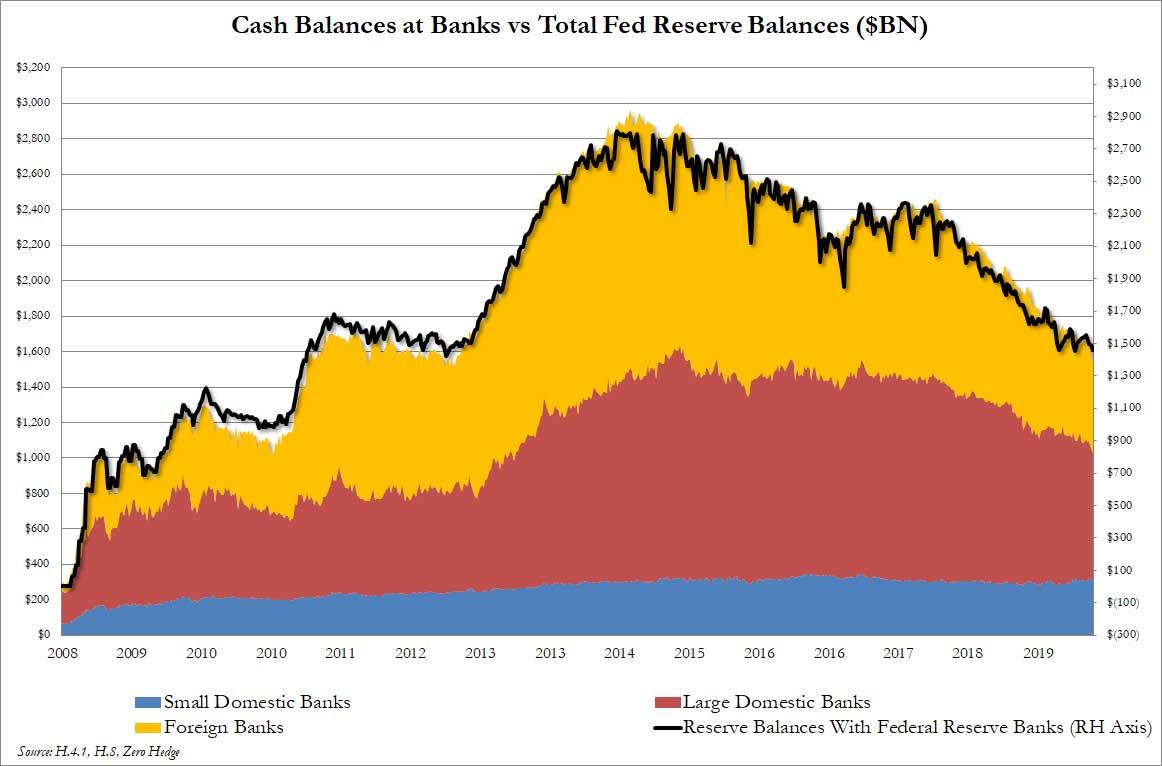

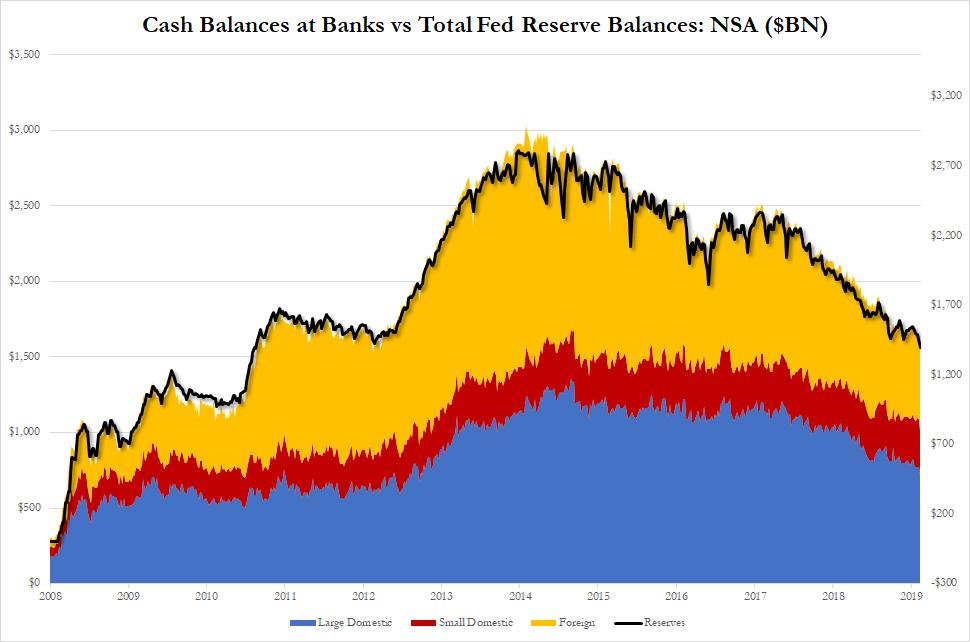

Last weekend, as the overnight funding crisis was peaking, we showed the distribution of $1.4 trillion in Fed reserves, also known simply as “cash”, across the banks that make up the US financial system.

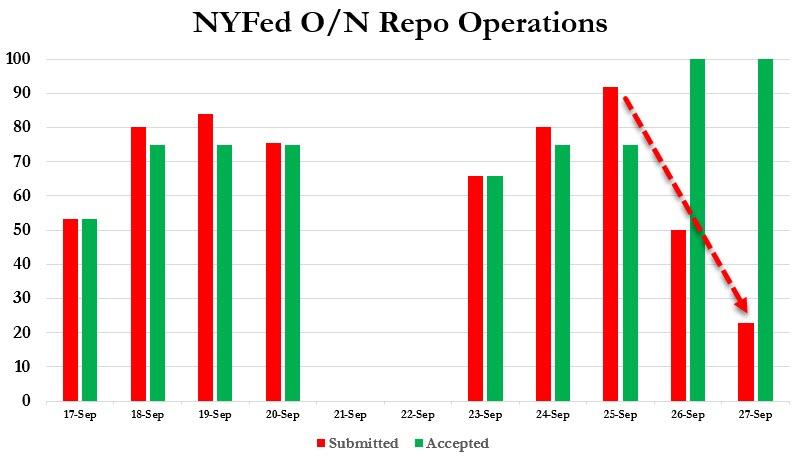

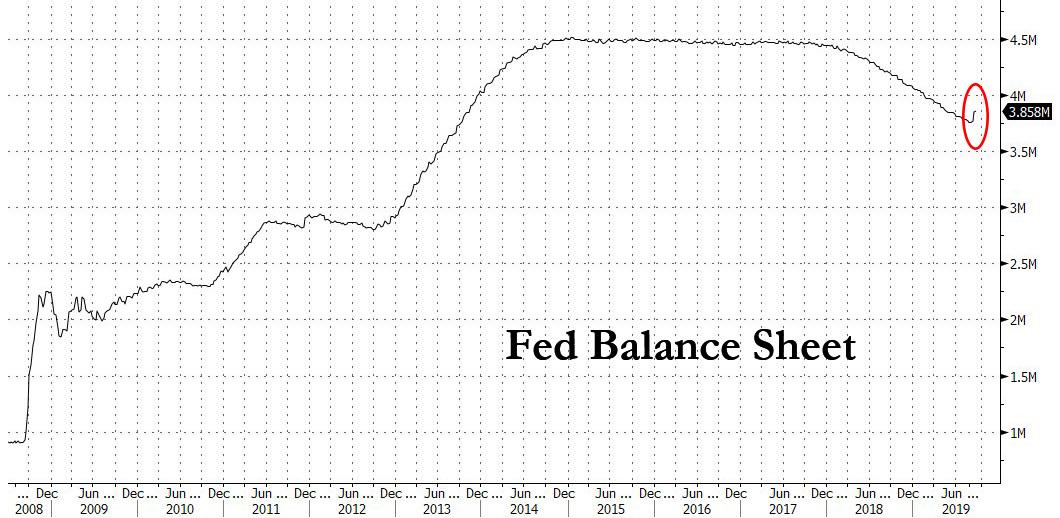

One week later, with the dollar “plumbing” shock seemingly unclogged as we approach quarter end, following $162BN in various term and overnight repo operations…

… which helped push the overnight G/C repo rate back down to 2.00%, questions are still swirling over events in the past two weeks that briefly sent the repo rate soaring as high as 10% as one or more banks found themselves on the verge of a funding crisis.

- The first question is what happened to prompt the sudden liquidity panic: while we know of the immediate events that led to a sharp drop in bank cash (reserve) levels such as the accelerated rebuild of the Treasury’s General (cash) Account at the Fed, the mid-month tax remittance to the Treasury, and the bulk settlement of Treasury bills, the fact that repo strains remained well into the next week and forced the Fed to drastically expand its repo operations, indicates that something far more serious was afoot than one time cash drains.

- The second, and perhaps even more important question, is which were the banks the catalyzed the initial funding shortfall, which then spread rapidly across the entire US dollar funding market. Here, as a reminder, even the NY Fed appeared clueless, with John Williams noting last Friday that the York Fed was examining “why banks with excess cash failed to lend to the overnight money market, following a week that revealed cracks in the US’s financial plumbing.”

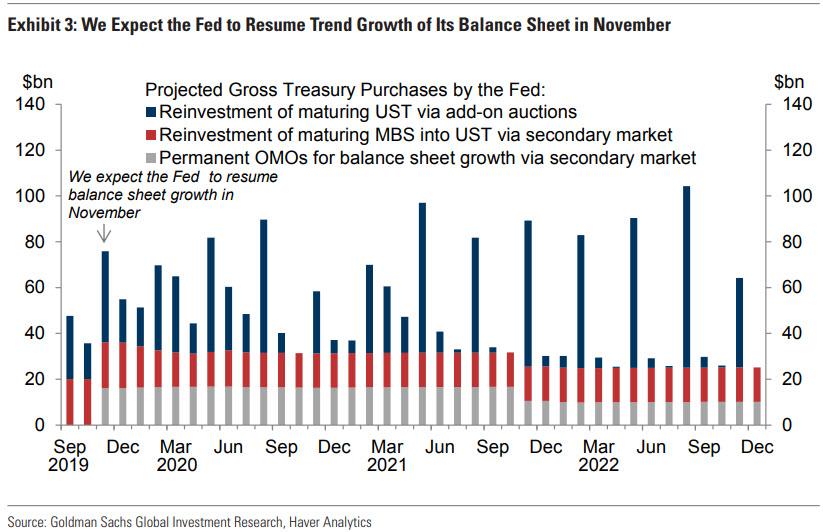

Setting aside what we don’t know – i.e., the immediate causes for the recent events and which specific banks were the catalysts – if we had to jot down what we do know, it is that it is now widely accepted that the level of “excess” reserves, at $1.4 trillion, is far too low for the financial system. As a result, first Goldman…

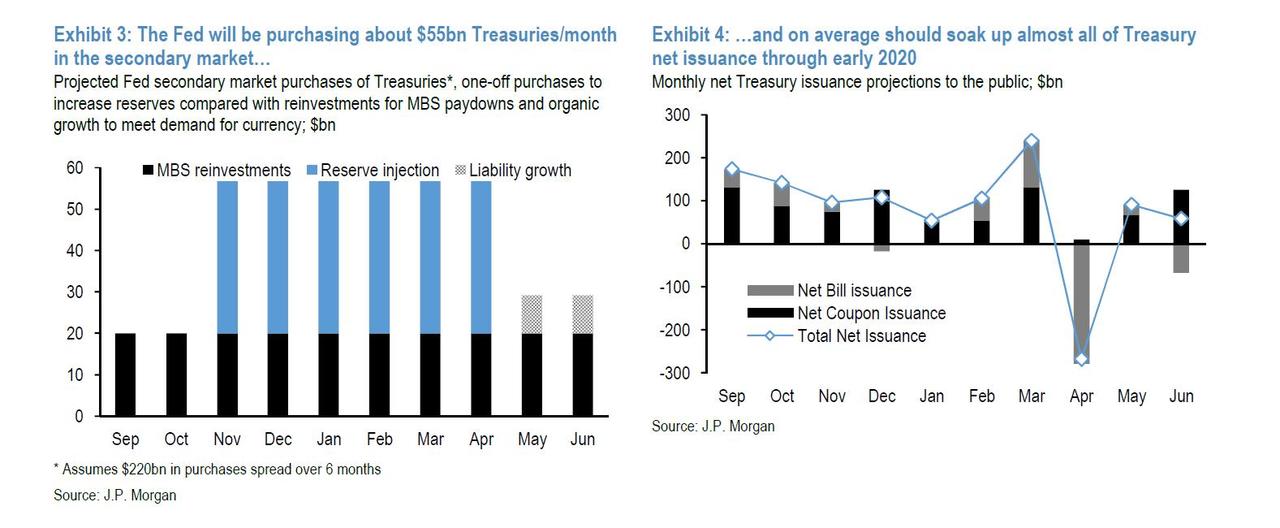

… and then JPMorgan now predict that the Fed will need to permanently inject billions in reserves – by way of Permanent Open Market Operations, i.e. purchases of Treasuries, i.e. QE 4 (just don’t call it QE 4 whatever you do) – starting some time in November, to elevate the overall level of reserves to roughly $1.7-$1.8 trillion.

Needless to say, a return of QE for a US Treasury whose fiscal 2019 deficit will be just around $1 trillion, and much more in 2020, and which needs to be funded in substantially by Treasury issuance, is just what the doctor ordered. In fact, as JPMorgan calculated, total secondary market purchases are likely to run at roughly $55bn per month through April 2020, and will represent almost all of Treasury’s net issuance over the period. In other words, the Fed is about to monetize the US deficit for the next six months, a handy backstop to the trade war should China decide to stop buying, or worse, dump its US Treasuries.

In fact, this line of thinking brings us back to what we said a little over a week ago: the real reason why the Fed needs to restart QE is simple: America’s exploding debt, and the need for someone to monetize it.

What is real reason for the Fed to restart QE as soon as today? This pic.twitter.com/P8c0fkTnLL

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) September 18, 2019

And all the Fed needed was a smokescreen, allowing it to resume the growth of its balance sheet, which for now is temporary and will, some time in November, turn permanent as Powell announces the resumption of direct Treasury purchases.

Here, a critical question as framed by Cumberland’s Bob Eisenbeis, remains unanswered, namely “the problem with proposals to increase the size of the balance sheet is that there is no guarantee that an increased amount of bank reserves would find their way into the various segments of the repo market where needed”, although we’ll cross that bridge when we get to it.

Yet even as the big picture behind the events of the past two weeks gradually emerges, one key question still lingers: which banks, caught in an unprecedented funding squeeze, caused the repocalypse which sent the rate on overnight cash exploding higher as their reserves suddenly found themselves no good in the tri-party repo market, and forced the Fed to launch its first repo operation in over a decade.

The answer, understandably, will hardly be provided: after all, in a time when the repo operation is the functional equivalent of stigmatizing discount window use, any dealer that is exposed as having funding issues could immediately face a bank run as its depositors and counterparties pull their capital, resulting in a liquidity – and solvency – crisis. It may explain why for nearly two weeks, there has been no media report over the culprits of the repo crunch, even though it would likely be the most widely read financial article of the year.

Hey financial reporters: here is a Pulitzer story for you – find out which bank(s) are so starved for $75BN in cash they are using the Fed’s stigmatizing overnight repo operation

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) September 21, 2019

And yet one can made some observations courtesy of none other than the Fed, which in its latest H.8 statement (“Assets and Liabilities of Commercial Banks in the United States“) released yesterday, showed the level of various bank asset and liabilities as of Wednesday, September 18, just as the repo crisis was starting. And the one, most important item here is the amount of commercial bank cash, i.e. reserves, broken down as detailed as the H.8 statement allows, which unfortunately only goes to the domestic (large and small) bank and foreign bank level.

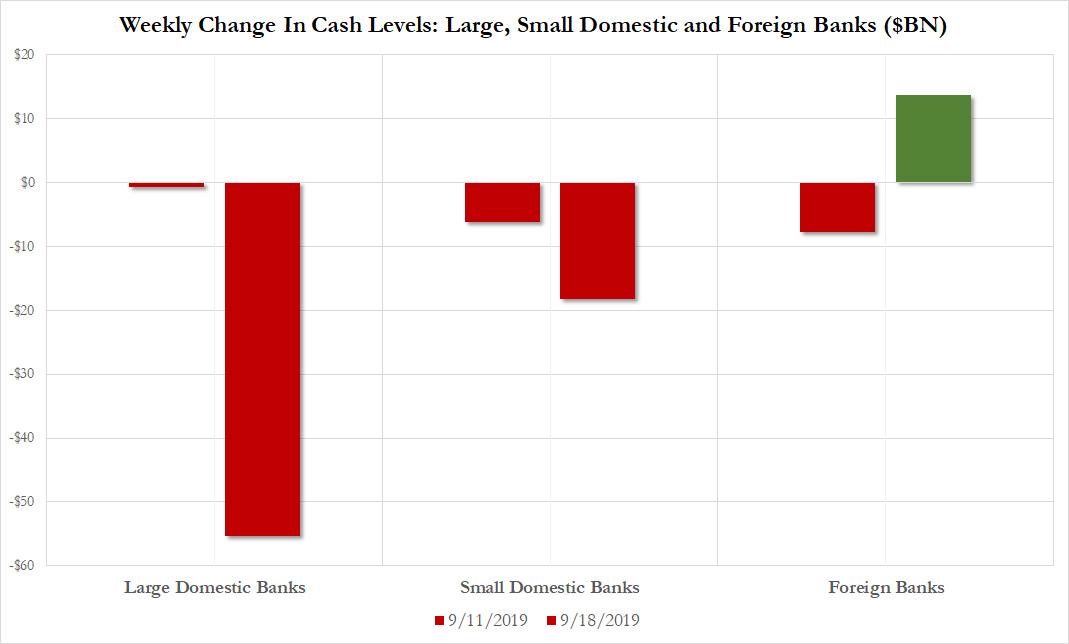

What this data shows is that on a non-seasonally adjusted basis (because we care for actual data, not the Fed’s smoothed take), cash at large domestic banks tumbled in the week ending Sept 18 by $55.3 BN to $714.8BN, the lowest total since April 2013, while cash at small domestic banks also dropped substantially, by $18.2BN to $272.9BN, for a combined $73.5BN drop in total domestic bank cash (from $1086.2BN to $1,012.7BN)

And so as cash levels, and reserves, tumbled, sharply draining liquidity out of the system, the Fed responded by announcing a liquidity injection almost precisely offsetting the $73.5BN total cash shortfall, in the form of a $75BN overnight repo operation after a decade-long hiatus, on Sept 19 one day after the Fed’s latest rate cut announcement.

The surprise? Whereas some had speculated that it was foreign banks behind the repo crunch, cash at foreign banks operating in the US rose by a respectable $13.6BN in the week ended Sept 18, to $537,8BN, in line with levels where foreign bank cash had been for much of the past two months.

In other words, to find the culprit for the latest repo shock, don’t look to Europe (those banks have enough pain on their plate with the ECB recently launching QEternity, to also have to worry about overnight funding in the US) but look for clues among domestic US banks.

Unfortunately, since the Fed’s data only goes through Sept 18, the full analysis of bank funding heading into quarter-end will need to wait until next Friday. Meanwhile, while we wait the question is: will the repo situation stabilize once we put September in the rearview mirror as so many rates strategists expect will happen once the quarter-end liquidity shortage fades, or will it persist confirming that something is well and truly broken in the dollar funding markets, and just what will the Fed do in response?

Tyler Durden

Sat, 09/28/2019 – 16:00

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2mGTPWV Tyler Durden