Surging China PMIs, Crashing Korea Exports Spark Even More Confusion About Global Economy

While markets and economists were quick to conclude the global economy had recovered from its post-2018 slump which had sent $17 trillion in bonds in negative yielding territory, some time in early September and that the widely anticipated recession of 2020 appears to now have been delayed amid growing speculation that the US and China appear to put the whole trade war nastiness behind us, the reality is that the global economic signs in the past three months have been mixed at best, with the Citi US eco surprise index sliding from a nearly two year high back to negative in mid-November, and now just barely peeking above the flatline.

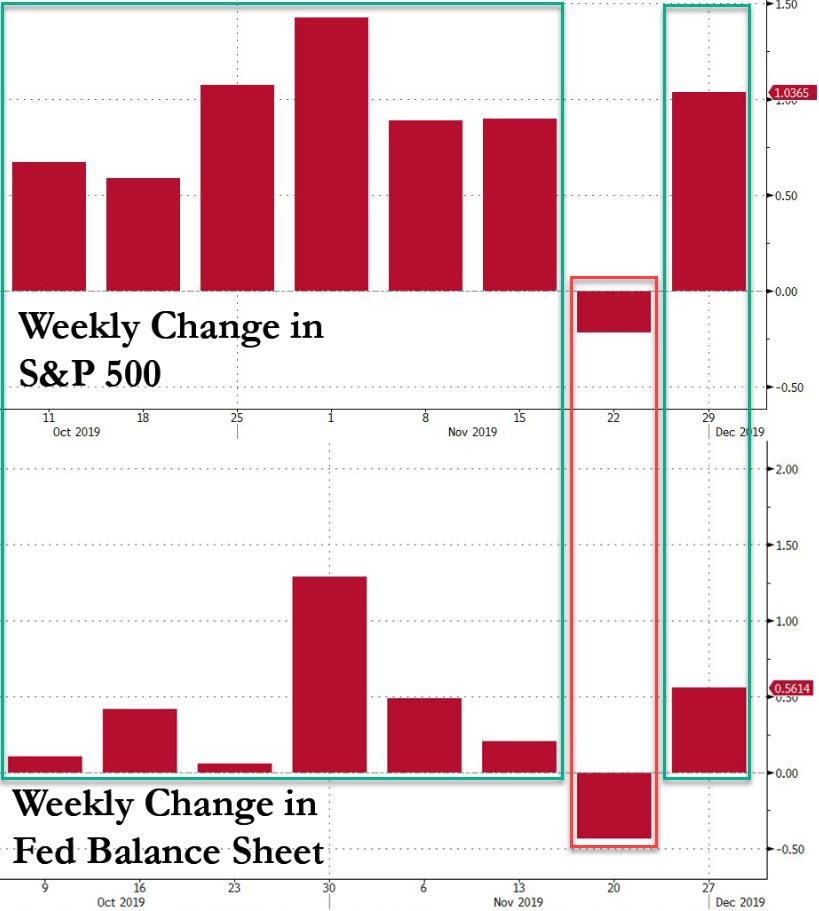

Of course, any such downshift in the economy is news to stocks which have continued to surge to all time highs courtesy of the Fed’s QE4 (sorry, we won’t call it NOT QE anymore for reasons we explained yesterday), rising every single week the Fed’s balance sheet has been increasing since the resumption of POMO in mid-October, and falling the one week the balance sheet shrank…

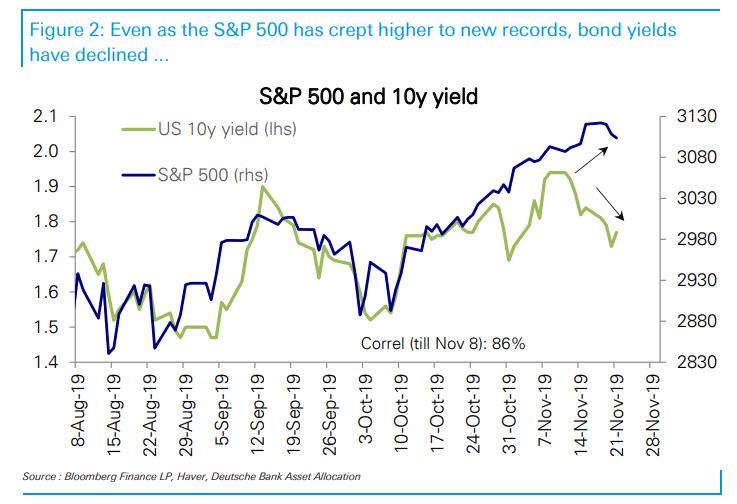

… even as virtually all other risk assets have peaked amid a surge in growth “jitters“, with bond yields dropping…

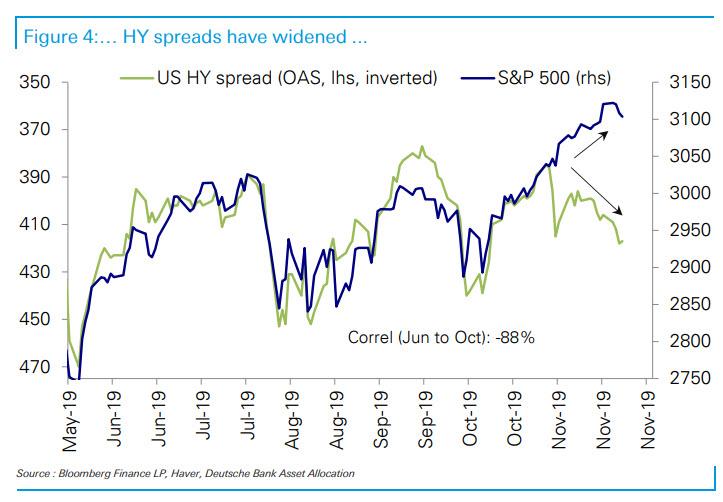

… junk bond spreads widening…

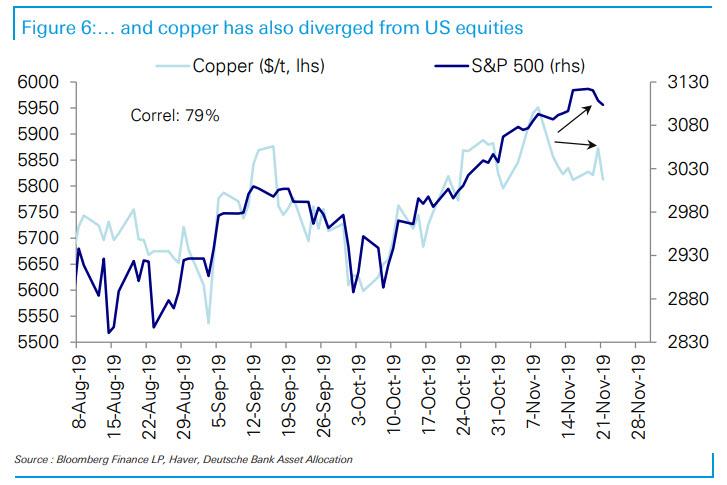

… and commodities sliding.

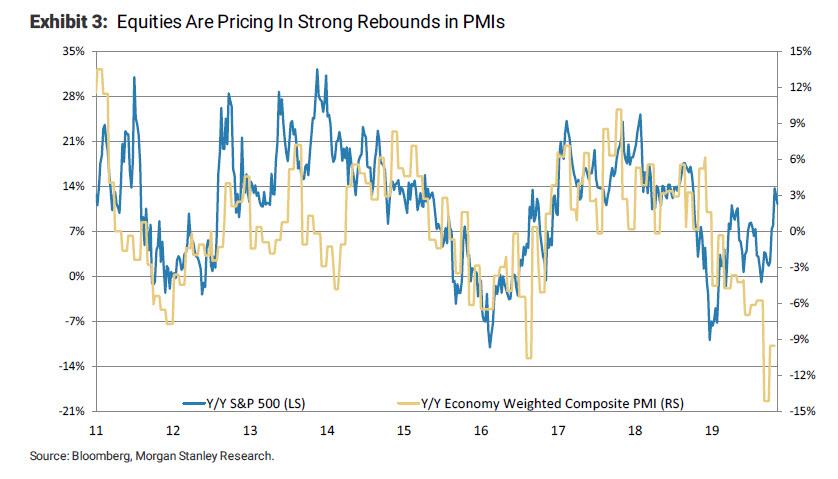

What is surprising is just how immune stocks have been to any adverse news; and while the Fed’s QE and record stock buybacks are certainly helping preserve the market’s optimism, one could in theory make a fundamental case that stocks have no priced in a full-blown economic recovery as the following chart from Morgan Stanley shows.

Which brings us back to the original question: is the modest recovery that flourished in early September, then wilted in the next few weeks, still on track or is it time to start pricing in a 2020 recession all over again.

Over the weekend we got two data additional economic points that provided only added to the confusion.

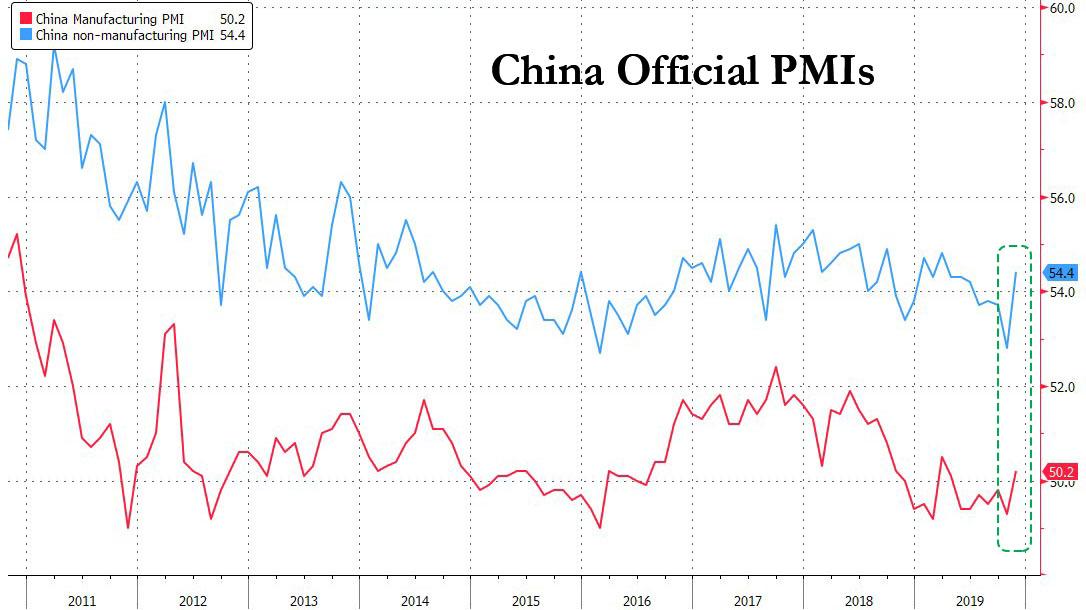

First, on Saturday morning (local time), China reported that its official manufacturing and service PMIs had both escaped from the sub-50 “contractionary” zone, with both prints beating consensus expectations.

Specifically, the official NBS manufacturing PMI came in at 50.2 in November, up from 49.3 in October, beating consensus estimates of 49.6, and the highest print since March. Meanwhile, the non-manufacturing PMI rose sharply from 52.8 to 54.4 in November, and also the highest since March.

Adding to the good news, both production and new orders sub-indexes suggested stronger growth momentum, and trade indicators improved. The production index was 1.8pp higher at 52.6, and the new orders sub-index went up 1.7pp to 51.3. The employment sub-index was unchanged at 47.3. Trade indicators – the imports sub-index – climbed 2.9pp (the largest rebound among manufacturing PMI sub-indexes) to 49.8, back to the levels seen around mid 2018; and the new export order index was also 1.8pp higher at 48.8, the highest reading since April. By enterprise type, manufacturing PMIs for large, medium and small-sized enterprises all increased in November.

It’s almost as if China’s factories have already priced in the end of the trade war, and are stating to restock for a year free and clear of tariffs. In retrospect, this may prove overly optimistic…

The non-manufacturing PMI (comprised of the service and construction sectors at roughly 80%/20% weightings, based on our estimates) rebounded to 54.4 in November, the highest reading since March this year. Services PMI rose to 53.5, a five-month high. Among sub-sectors in services, property, railway transportation and catering saw weaker growth momentum while production related services, logistics, telecom, capital markets and insurance sub-sectors saw stronger growth momentum. The construction PMI fell by 0.8pp to 59.6, modestly below the average level of more than 60 over the past two years.

Putting the two together, China gave a clear sign that the economic storm clouds are dispersing, while the combination of better import sub-indexes and lower finished goods inventory pointed to stronger demand, and the NBS attributed the better new export orders to “more foreign demand ahead of the Christmas holiday”. Commenting on the data, Goldman said that the fading of payback effects after earlier export front-loading, as well as early signs of better global growth, likely contributed to the rebound in new export orders. The dissipation of potential drag on some activities around the October 1 celebration of the 70th anniversary of the PRC might have also added to the recovery in PMI indexes in November (average reading of October to November NBS manufacturing PMI is 49.8, slightly higher than the average reading in the first nine months of this year). The stronger manufacturing PMI also helped with a better services PMI – production related services and the logistics industry saw stronger growth momentum in November.

Still, one naturally needs to take the Chinese PMI surveys with a grain of salt: after all, there is no country on earth more prone to manipulating and goalseeking its “data” as the political narrative may fit, and of all the data, the PMI happens to be the most malleable. As such we would wait for separate confirmation that China is now in the clear, especially following the recent collapse in China Industrial Profits which plunged to an 8 year low. If the PMI data was indeed just a fabrication, expect no rebound in this far more important and tanbile data set.

Then again, one may not even have to wait that long, because in addition to China’s latest PMI prints, over the weekend we also got the latest South Korean export data, and it was a doozy.

The data, which is a closely watched bellwether for world trade and a leading indicator for global corporate profits, not only plunged again, but dropped far more than expected in November, dealing what Bloomberg dubbed “a blow to nascent optimism that a prolonged slump in global demand may be bottoming out”, the same optimism Bloomberg was cheering on just one day earlier with the Chinese data.

In November, trade ministry data showed that exports tumbled 14.3% from a year earlier for a sixth straight double-digit decline; the drop was about a third worse than the 9.7% slide consensus expected, and refuted preliminary figures which had also offered hope of some respite in the export slide. This was the second worst annual export drop in the past 4 years, and one of the worst months for Korean trade since the financial crisis. At the same time, imports decreased 13% y/y.

Exports to China dropped 12.2% in November from a year earlier, reflecting slowing growth in the world’s second largest economy and South Korea’s biggest export destination. Exports to Japan fell 10.9%, while imports declined by 18.5%, as the two neighboring countries go through their own trade dispute. Japan said in summer that it would impose tighter checks on its exports of gas and two other materials used in the tech industry, citing national security concerns. The ministry said the materials make up only 1.4% of Korea’s total imports from Japan and haven’t yet caused any disruption to production.

The export numbers confirm that the Asian country is on course for its weakest economic growth in a decade. The BOK on Friday slashed its growth projections for this year and next by 0.2% points to 2% and 2.3%, respectively. That according to Bloomberg would be the slowest pace since 2009 when the country suffered in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Other key indicators like industrial output and consumer prices have also been pointing to deteriorating demand, but the government has few policy options left to support the economy, with rates already at all time lows, while expansionary fiscal and monetary policies are pushing household debt to all-time highs as people borrow more to invest in the domestic property market in search of higher yields. That in turn is jeopardizing President Moon Jae-in’s pledge to provide affordable homes.

“Korea is not the only casualty of the U.S.-China trade dispute, a slowdown in the global economy and no-deal Brexit,” the ministry said, noting that most of the world’s 10 biggest exporting countries had seen shipments decline as of September. “We’re particularly harder hit because of heavy reliance on China by region and semiconductor by sector.”

That said, Korea did everything it could to give the impression that its dismal data was also set to turn higher: Bank of Korea Governor Lee Ju-yeol insisted two days ago that the economy was passing through its most painful moment and talked of a gradual recovery next year. Still, the latest data suggests that any optimism may be premature.

As Bloomberg notes, South Korea’s trade figures have gained particularly close attention in recent months as markets try to infer whether the worst of a tech sector slump is over and how quickly it might recover. Korean companies such as Samsung Electronics are among the world’s biggest suppliers of semiconductors, smart-phones and other tech-related items. The November data showed that chip exports, the largest category in Korea’s overseas shipments, dropped 30.8%, compared with falls of more than 30% in recent months.

South Korea’s export-dependent economy has been one of the hardest-hit by the U.S.-China trade war and the disruptions it has caused in the global supply chain, with almost 40% of the nation’s shipments headed to the two countries. The government, just like the US stock market, has pinned its hopes on an export recovery next year as the U.S. and China move towards a preliminary trade deal.

That said, with just two weeks to go until Trump and Xi have to conclude a Phase 1 deal or else the US is set to trigger more tariffs, optimism of a deal may disappear quickly if no progress is made in the coming days.

Tyler Durden

Sun, 12/01/2019 – 13:05

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/34ESNvw Tyler Durden