New Study Shows Average U.S. Worker Needs 53 Weeks In A Year Just To Earn “Middle Class” Lifestyle

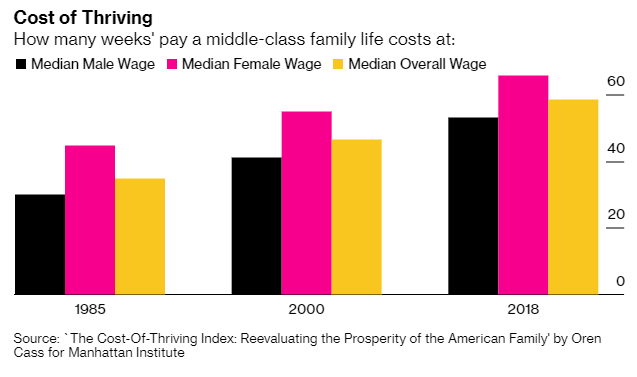

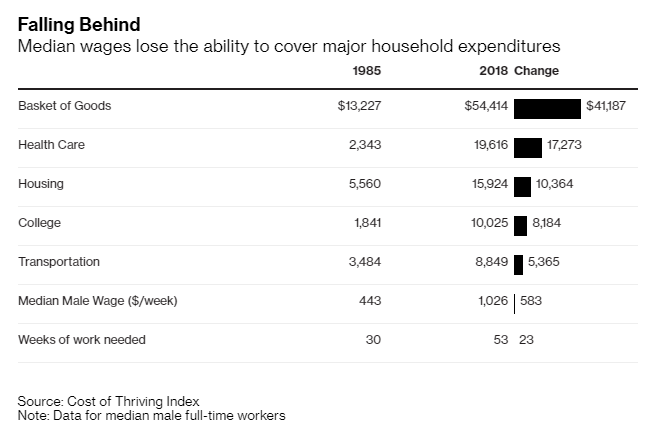

A new study by Oren Cass at the Manhattan Institute confirms that a 52 week year just doesn’t cut it for the average American worker looking to simply make a “middle-class” life for themselves. For women, the news is even worse: it requires 66 weeks to earn a middle class lifestyle.

These figures compare wildly to 1985, when males at the median weekly wage needed to work only 30 weeks and women only needed to work 45 weeks, according to Bloomberg.

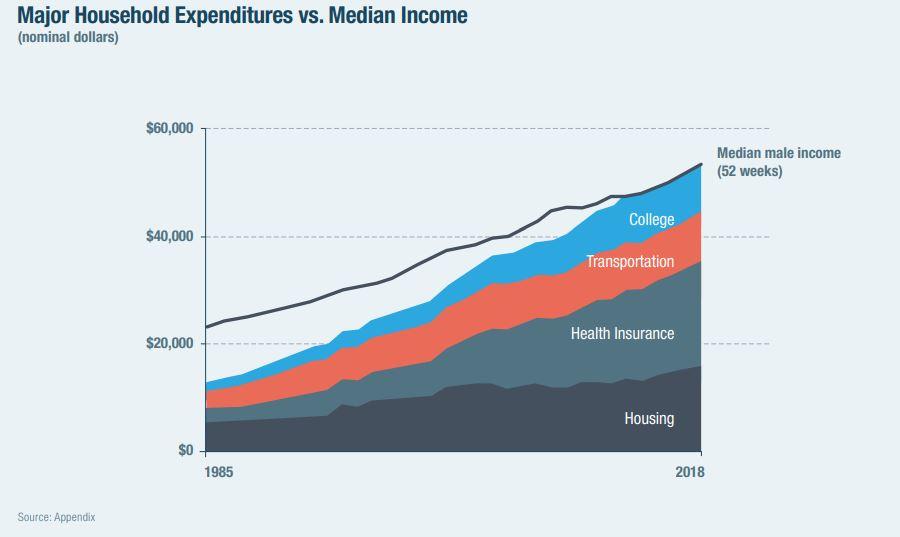

The paper tried to compile a “cost of thriving” index for the purposes of gauging quality of life. The “middle class” is defined as a 3 bedroom house just below the mid range of market prices, family health insurance, costs associated with a vehicle and a semester at public college.

The study’s author, Oren Cass, is a former adviser to Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign. He says that while his index is imperfect and it doesn’t account for wide cost and income difference, it’s a “starting point”. It also doesn’t account for larger houses, advances in medicine and safer cars.

Cass introduces the problem by saying: “A dramatic divergence between data and experience is confounding America’s policy debates. The data seem to show that households have attained unprecedented prosperity, and wages have (at worst) held their own against inflation, or (at best) risen much faster than prices. By conventional measures, material living standards everywhere in the income distribution are at all-time highs, and technological progress continues to improve them.”

He continues: “Yet many jobs able to support a family in the past no longer do. Millennials are in worse financial shape than were those of Generation X at the same age, who themselves had fallen behind the baby boomers. The stories appear irreconcilable.”

Cass thrashes the case that quality of life has improved enough to outpace inflation and the widening inequality gap. He says workers don’t always have the option to substitute worse, but cheaper, goods if their incomes aren’t rising fast enough to afford newer and better products.

He also found that only incomes among men holding Bachelor’s degrees have risen more than consumer prices since 1980.

Cass concludes: “The explanation is this: inflation does not measure affordability. Key assumptions built in to inflation indexes for the purpose of measuring the underlying, economy-wide upward pressure on prices are different from, and often counter to, the key assumptions necessary for assessing the economic choices and constraints faced by households. When analysts use inflation adjustments to compare household resources over time, they have chosen the wrong vantage point, and their view is obscured.”

His study also concludes that economists and families see three things differently:

-

Quality Adjustment. Products and services that rise substantially in price but in proportion to measured quality improvements can become unaffordable, while having no effect on inflation.

-

Risk-Sharing. New products and services can increase costs for the entire population yet deliver benefits to only a very small share, while having no effect on inflation.

-

Social Norms. Society-wide changes in behaviors and expectations can alter the value or necessity of a good or service, while having no effect on inflation.

You can read Cass’s full analysis here.

Tyler Durden

Fri, 02/28/2020 – 18:45

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2vpP2O4 Tyler Durden