China Will Use “Coercive Power” To Force Digital Yuan On Population

It was supposed to be the biggest threat to the reserve status of the dollar (China’s denial that it has no desire to replace the USD with the digital yuan only confirms it) since the failed experiment that is the “whatever it takes” euro, but instead it is turning out to be one giant yawn.

While many pundits have argued that China’s digital yuan would be a “potentially fatal challenge” to American hegemony according to historian Niall Ferguson, Templeton’s Hasenstab saying it could undermine the dollar’s role as a reserve currency and even Biden’s White House studying the potential threats to the US currency, one month ago we reported that those who’ve actually used the digital yuan in China offer a vastly different response: big shrugs of indifference.

After interviewing users of China’s digital currency, Bloomberg noted that they showed little interest in switching from mobile payment systems run by Ant Group and Tencent that have already replaced cash in much of the country, with some openly balking the digital yuan – which recall is programmable and comes with an ad hoc expiration date – and which gives authorities access to real-time data on their financial lives.

“I’m not at all excited,” said Patricia Chen, a 36-year-old who works in the telecom industry and was one of the more than 500,000 people in Shenzhen eligible to take part in the trial. The lukewarm responses of the seven participants in China’s great monetary experiment underscored the major challenge facing President Xi’s government as it lays the groundwork for adoption at home and abroad. And, as we noted last month, “even if authorities ultimately convince – or rather force – citizens to embrace the digital yuan, it’s unclear how they can do the same with international consumers and businesses already wary of China’s capital controls, Communist Party-dominated legal system and state surveillance apparatus.”

It’s also why with the Yuan’s share of global payments seemingly capped at around 3% in recent years – in no small part due to China’s closed capital account and great monetary firewall – a digital version of the currency is unlikely to boost its share by much more than 1 percentage point, according to Zennon Kapron, managing director of Singapore-based consulting firm Kapronasia.

“The global impact will be very small” barring structural changes to China’s economy and financial system, said Kapron, author of “Chomping at the Bitcoin: The Past, Present and Future of Bitcoin in China.”

Those familiar with China’s grand ambitions suspect that Xi has high hopes for international use of the digital yuan as he tries to lessen his country’s reliance on the U.S.-led global financial system. But so far at least, Chinese policy makers have given mixed signals about their ambitions in public.

As Bloomberg reports, Zhu Jun, head of the central bank’s international department said in an article last month that China faces an “important window” to promote global use of yuan as U.S.-China decoupling threatens to spread to finance from trade, technology and investment. She said China “should take advantage of the early progress” in the digital yuan’s development to explore potential areas for internationalization.

There is just one problem: nobody can figure out why they need to use a digital currency which allows authorities to snoop on their every activity, when existing alternatives offer everything the digital yuan can do.

And speaking of China’s “coercive” tactics to force its currency upon the population, over the weekend Bloomberg penned an op-ed about the digital Yuan that suggests it might be soft launched with the 2022 Winter Olympics; and that it may operate more like the Hong Kong Dollar than a Central Bank Digital Coin, in that the liability may sit on the commercial issuer’s balance sheet, fully backed by CNY reserves. This – as Rabobank’s Michael Every writes – obviously won’t make it very attractive to banks, businesses, or consumers happy with current e-payment systems. As the op-ed notes, one would then have to *compel* them to use it via “the state’s coercive power.” For example, paying civil servants in e-CNY; or, more importantly, demanding tax payment in e-CNY to force people to earn them, so creating a natural demand.

The full op-ed from Bloomberg’s Andy Mukherjee is below:

Digital Yuan May Prove Hong Kong Dollar’s Cousin

The stronger the interest in China’s coming digital currency, the less we seem to know about it. Sifting through comments by officials thought to be the brains behind the project, Capital Economics’ chief Asia economist Mark Williams has raised an interesting question: What if the e-CNY, as some are beginning to call the new electronic cash, is not at all a central bank digital currency?

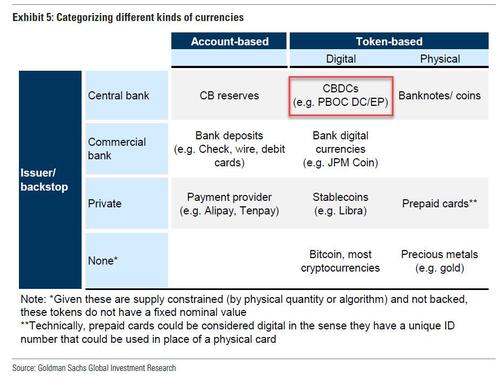

Most of us are by now familiar with electronic money, but popular apps like PayPal or Alipay are linked to bank accounts. A true central bank digital currency will bypass lenders and make us directly the customers of monetary authorities. We’ll use the liability of a central bank to pay for coffee or a book.

The excitement with the digital yuan — or the FedCoin or BritCoin — is precisely because of this: Tokenized money is supposed to be an IOU of a central bank, just like physical cash. We may use an ATM to draw down our accounts, but as soon as we do, the bank owes us less. The state owes us more. Digital cash has been conceptualized the same way. When we transfer funds from a savings account into our digital wallets, the commercial bank goes out of the picture, and the central bank steps in. Tokens make credit risk disappear from settlements. Transactions can remain anonymous unless the monetary authority wants to lift the hood to check for money-laundering.

However, if Williams is right, then e-CNY, which is believed to be heading for a soft launch coinciding with the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, may not be a claim on the People’s Bank of China. Then, “It isn’t strictly a CBDC at all,” he says. It may, in fact, be a digital relative of the Hong Kong dollar.

Since 1846, banknotes in the city have been the liability of commercial issuers. The three banks that supply everyday money maintain full reserves with the Hong Kong Monetary Authority. That’s why nobody sitting on a pile of Hong Kong dollars is anxious about the creditworthiness of HSBC Holdings Plc, Standard Chartered Plc or Bank of China (Hong Kong) Ltd.

Digital yuan may have a similar design, according to Williams’s reading of former PBOC Governor Zhou Xiaochuan’s statements. The e-CNY will be the liability of the bank or fintech sponsor of digital wallets. They will issue tokens, each worth 1 yuan, and they will maintain reserve assets in their accounts with the central bank in the ratio of 1:1.

Customers sleep easy, though there’s a cost for intermediaries. Suppose a saver has 100 yuan in a Chinese bank. The major institution that holds her money has to keep 12.5% in required reserves with the PBOC. The rest is free for the lender to seek the best possible return. If the user moves funds to her e-CNY wallet, the bank would have to keep the full 100 yuan with the PBOC. In a pure digital currency model, the bank would have lost the entire deposit, something that no central bank running a digital cash pilot or experiment wants. However, if to retain a deposit, the lender has to put up cash for the entire amount, it may still be forced to curb advances. What bank would embrace a product like that?

That’s one reason why Williams seems to think that the digital yuan will be a hard sell. Consumers in China are already getting all the flexibility they want with Alipay or WeChat Pay, which are entrenched and offer highly innovative uses. Similarly, banks will be loath to lock 100% of even a part of their deposits in idle reserves. The duopoly of Alipay and WeChat Pay, which processes 94% of China’s third-party mobile-phone payments, will be reluctant to give up their rich harvest of consumer data.

So how to make the digital yuan work?

A neat solution — as with every form of money, according to the Chartalist theory — is to use the state’s coercive power. All that authorities need to do is to pay civil servants and demand tax payments only in official digital currency. Payment platforms will then have no option except to offer an e-CNY alternative. In a few years, offering customers such a choice might even become mandatory.

As Williams says, “Left to the market, e-CNY is unlikely to succeed. But the government doesn’t have to leave it to the market.”

China’s long-standing ambition to challenge the dollar’s hegemony in global commerce hasn’t gone anywhere. A digital yuan that’s a popular means of payment overseas, especially in the Belt-and-Road network, would reinforce that goal. But before that, Beijing has to ensure widespread domestic use. So policy makers’ more immediate motivation may be to curb the sway of local tech titans, with minimum damage to banks’ deposit base.

The final architecture of the new currency is still unknown, but conceiving e-CNY as a cousin of the Hong Kong dollar — a synthetic central bank digital currency issued by banks and payment firms — and flexing the muscles of state power might tick most of the boxes.

Tyler Durden

Mon, 06/07/2021 – 20:40

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2T89heC Tyler Durden