The Death Of Commuting

By Nick Colas of DataTrek Research

The rising interest in remote work is largely an American phenomenon and an important trend to understand for its long-run impact on US productivity growth. The bottom line is that remote work is here to stay; workers hate commuting. The increasing popularity of remote work combined with new technology should lead to higher US productivity than the last 2 decades.

This is a story about commuting and the increasing popularity of work-from-home, and we will start with an anecdote:

Many of you know I grew up in New York City (Upper West Side Manhattan, to be precise) in the 1960s and 1970s. Since my parents both worked, I was on my own getting to and from school and any after-school activities. I learned at a very early age (8-9 years old) how to read people on the street, look for trouble and avoid it, and generally navigate what was then a not very safe city.

The families of many childhood friends moved to the suburbs during this period and, when we visited them, I always wondered why we couldn’t live that way. It seemed a lot nicer. Trees, outdoor activities, backyards … It was like another world.

When I asked my mom why we couldn’t live in a house too, her reply was always “Your father refuses to commute”. He worked in midtown Manhattan and wanted to be able to wake up at 8am but still be at his desk by 9am, even if he had to walk. Nothing would sway him from that point of view. In truth, my mother had her own reasons for staying put. She wanted her children to have a cosmopolitan upbringing. Long story short, we never moved.

Copious amounts of psychological research has since validated my father’s seeming stubbornness: commuting is an unalloyed negative for mental health. Because it is inherently unpredictable, it creates stress. The longer the commute time, the more stress there is. This affects both job performance and general life satisfaction. Commuting is also expensive. Assuming a typical American commute of 40 miles/day and $3/gallon gas prices, that works out to $1,500/year. Mass transit into a major US city like NY can cost several hundred dollars/month.

I think this is the most important and still underappreciated story about the work-from-home phenomenon and it applies to the United States much more than, say, Europe. Here’s why:

-

Daily commute times are actually about the same between the US and the EU – about 25-27 minutes each way.

-

But … Americans work an average of 1,767 hours/year according to the OECD. In France, for example, it is 1,402 hours/year and in Germany it is 1,332 hours/year.

-

That’s an average differential of 400 hours/year, or almost 2/hours a working day. Some of this difference is due to vacations, of course. Still, the net result is that Americans work many more aggregate hours AND must also budget time for their essentially 1-hour typical commute.

Millions of American workers have, over the last 16 months, seen what a non- or less-commuting life looks like and (no surprise) they really like it. It may not put them on par with their French and German counterparts but clawing back an hour of their work-related day closes the gap by half. The financial savings obviously help as well, as does the possibility of relocating to lower-cost parts of the country if entirely remote work is a possibility.

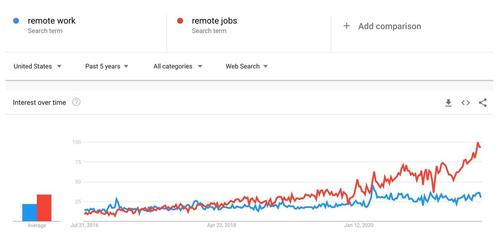

That’s why US Google search volumes for queries like “remote work” and “remote jobs” remain higher than pre-pandemic levels (the former) or still rising quickly (the latter):

I see echoes of this fact everywhere in the current US labor market data, but the most important systematic issue is what it will do to American labor force productivity over the next economic cycle. Economic growth is a function of just 2 factors: labor force population growth and how much the average worker can produce. We know the American population only grows at about 1 percent, so getting real GDP growth to run hotter than that requires workers to increase their output every year. That is productivity growth, and it is also the engine of wage growth.

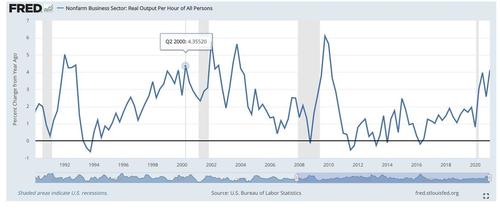

This chart shows US labor force productivity back to 1990. The choppiness is due to recession effects (those spots to the right of the grey bars), but the trend is clear enough.

Peak US structural (i.e., non-cyclical) productivity was in 1999 – 2000 (3-4 pct, as noted). That’s what you’d expect to see given the widespread rollout of Internet 1.0 and personal computing.

Since then, normalized productivity has declined. In the early 2000s cycle it was 1-3 pct (2004 – 2007) and more like 0-2 pct in the last cycle (2011 – 2019).

The bottom line is that US labor force productivity has been in secular decline for 2 decades and how the shift to remote work affects it will be a determining factor in US economic growth over the next decade. One can just as easily paint a rosy or dire picture:

-

Positive: less commuting means less worker stress and a happier, more focused workforce at the margin.

-

Negative: less human contact and in-person supervision/training will lead to lower growth in output/worker.

The “DataTrek take” is that US labor productivity will rise from last decade’s lows because of two factors. First, labor shortages are forcing companies to invest heavily in productivity solutions. Good news for structural profit margins, but bad news for many workers who may be sitting out the current hot labor market environment. Second, venture capital is funding a raft of new companies that are creating the next wave of productivity-enhancing software.

I’ll close with another story, this one about the use of electricity at the start of the 20th century. Thomas Edison had started running commercial generators and selling electric power in the 1880s, but through the 1910s most factories still ran steam-powered machines. It took the post-World War I boom to see them convert to electricity. This allowed factory owners to lay out their shop floors to maximize output rather than needing to locate power-hungry devices closest to the steam engine. Efficiency increased dramatically (link below to a BBC article with more details).

We are in a similar position today. As with electricity in 1910 the technological infrastructure is in place for a productivity surge, but it is deeply underutilized. Persistent labor market shortages are the catalyst to change that. Yes, this will require worker retraining, but the 1920s US economic boom shows technological shifts need not lead to structurally high unemployment.

Sources: BBC Article on the adoption of electricity: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-40673694

Tyler Durden

Mon, 08/02/2021 – 14:55

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2WP0gZR Tyler Durden