What The Great Ammunition Shortage Says About Inflation

Authored by Matt Stoller via BIG Substack,

Concentration is increasing prices and keeping them high. The ammunition duopoly and the “Great Ammunition Shortage” is just one example.

Covid has done a lot of things to our society. But talk to anyone who enjoys hunting, and they’ll tell you one of result is the ‘Great Ammunition Shortage of 2021.’ “5.56 ammunition for an AR-15 used to be about 33 cents a round,” said Mark Oliva, director of public affairs for the National Shooting Sports Foundation. “Now you’re looking at closer to almost a dollar a round. So it is much more expensive and it is much more difficult to find ammunition.”

One of the more interesting questions in the discussion over inflation is the relationship between concentration and pricing changes. Most economists believe that supply shocks are increasing profits, but that this increase will serve as an inducement to more productive capacity. “Capitalism is on our side,” said economist Alan Blinder in the Wall Street Journal. “Shortages raise prices, but high prices create opportunities for profit, which attract capitalists to alleviate the shortages.” If Blinder were correct, then one would expect lots of new productive capacity and new entrants into this market.

Ammunition is a highly concentrated industry. There are many ammo brands, like CCI, Federal, Remington, Winchester, and Speer, but they are all controlled by two firms – Vista Outdoor and the Olin Corporation. As Elle Ekman wrote in the American Prospect, Vista and Olin rolled up the industry through mergers, as well as taking advantage of the privatization of government facilities making ammunition and government contracts.

During the pandemic, a lot of people decided they wanted to buy and use guns, either for hunting or personal protection. The 12 million new gun owners, plus existing activity, meant that the industry experienced the same demand shock that lots of outdoor activity segments saw. The result has been a shortage of ammunition, and higher prices.

Like a lot of industries, there are cost pressures in ammunition; the price of raw materials, like brass, have gone up. Additionally, the State Department has blocked imports from Russia, adding to the pricing pressure. But the cost story is really a sideshow; the pricing increase is going almost entirely to profit. For Vista, margins skyrocketed in 2020, and continued to increase in 2021. As the CFO of Vista, Sudhanshu Shekhar Priyadarshi, told investors in November, margins rose to a record 27% in Q2 of 2021, on top of an already extraordinary 2020.

According to Blinder, and most economists, competitors should enter the market and invest in new factories, or existing firms should expand existing capacity to seize market share, eventually leading to reduced prices. But the industry hasn’t experienced such competitive dynamics. Profits, said Priyadarshi, have gone to share repurchases and paying down debt.

There are several reasons for this, but the main ones are consolidation and high barriers to entry in the industry. Ammunition is difficult to produce, as it requires careful manufacturing processes to safely handle explosive materials. Vista recently bought its competitor Remington out of bankruptcy, lowering the number of firms in the industry that could even build a factory and distribute ammunition effectively. And the limits on capacity were explicit. The head of ammunition for Vista, Jason R. Vanderbrink, explained that the “most important” reason for the Remington acquisition was “added capacity to Vista without increasing the overall market capacity.”

This isn’t purely a story of informal cartel engaged in profit-seeking, but also risk-management. Like a lot of commodity businesses, the ammunition industry is cyclical, with shortages and price hikes when demand increases, followed by collapses as capacity increases and demand stays level or declines. Industry executives know this, and are intent on that not happening again. Here’s Christopher T. Metz, the CEO of Vista, talking about their purchase of Remington, a competitor in the industry.

Because of some of the consolidation we’ve done with Remington, even if you look long term, we don’t see the same type of price compression the industry may have experienced in previous times.

Vista has set up two pricing programs to ensure high prices and stability. The first is a subscription service for ammunition, which gives them a steady flow of ammunition demand and lets them plan production more easily. The second is, well, an informal form of price-fixing, or output reduction. They aren’t totally explicit about it, but they use code words to make the point. Here’s Metz explaining that they collude with their competition to keep capacity lower than it should be.

“Now with ammunition being the largest part of our business. I mean, clearly, buying a Remington, we’ve created what we feel like is an even more disciplined industry now as we go forward. We’ve got, I think, like competitors in the sense that they watch growth, they watch their margin profiles. And we feel like we’ve got a disciplined industry.”

And I’ve mentioned previously that we studied, as best we can…industry capacity and making sure that we’re not only managing our capacity, but very mindful of what’s being brought into the industry, so we don’t get over our skis, if you will.

In other words, Vista executives are planning to ensure that prices won’t come down. They have expanded some capacity on the margins, but because there are only two real firms now, they can easily pull that extra production offline if necessary. We’ve seen the management of pricing across economic cycles in other concentrated industries. Chris Leonard wrote about Tyson Food’s control of the poultry business, and how during the financial crisis this meant the entire industry could raise prices by all cutting production at once.

No one in the room was excited about the idea of a production cut. It was Tyson’s nuclear option. It meant the company would intentionally scale back its business, cutting down its sales. It also meant farmers would get fewer deliveries of chickens, reducing their income even as their debt payments stayed the same. But Smith decided that a cutback was inevitable.

Ultimately, Tyson cut its production by 5 percent in December. Around that time, the industry as a whole was estimated to have cut back the placement of new eggs between 6 and 7 percent.

In a matter of weeks, the price of a boneless, skinless chicken breast rose by about 20 cents, according to an industry estimate. Within a short few months, Tyson’s chicken business was profitable again.

What was remarkable about this plan was the fact that Tyson executives could even consider it. Decades of lax antitrust enforcement allowed Tyson Foods to buy most of it competitors, giving executives at company headquarters the ability to control production on thousands of farms and dozens of major poultry plants across the nation. In 2008, Tyson Foods and its competitor Pilgrim’s controlled more than 40 percent of the national market. The third-biggest company controlled just 8 percent. Modern American farming was run out of the central office.

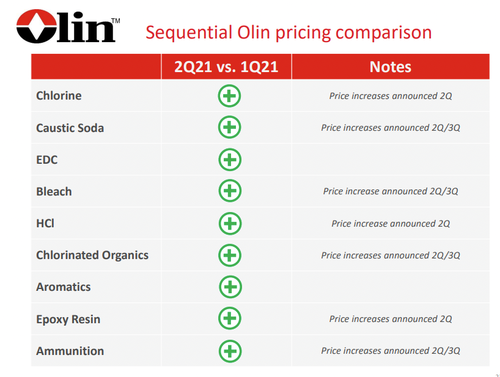

If meat-packers were doing this fourteen years ago, then what is happening in the ammunition industry shouldn’t be a shock. Vista and Olin, in other words, are following the legal framework laid out more than a decade ago. In fact, we can see that within the ammunition industry itself, since Olin is more a chemical conglomerate, and its ammunition division is something of a sideshow. But that firm’s leaders are also excited about margins and price increases across their whole suite of products.

Barriers to Entry

When economists like Alan Blinder, Jason Furman and Larry Summers, discuss inflation and concentration, they are relying on the idea that markets are competitive, and that new entrants will drive down margins of existing players. This is not a crazy theory. Some bottlenecks will go away; Congress is acting to reduce the problem at the ports, otherwise known as the world’s most profitable traffic jam.

But in terms of concentrated industries, is it really true that there will be mass entry with high profit margins? As we see with ammunition, the answer is, probably not.

This relates to an interesting question in antitrust law, which is the idea of barriers to entry. Such barriers can be financial or technical, such as the expertise and expense needed to enter many industries. But as antitrust law has weakened, it’s also made it much harder for new firms to come into concentrated markets. Let’s keep going with Tyson Food. As New York Times reporter Pete Goodman tweeted, independent meat-packers actually can’t enter the market to compete with Tyson, even if they can built out facilities.

Striking, though, that there’s no involvement of retailers, no? Ranchers have told me that capital isn’t the barrier to launching slaughterhouse capacity; it’s the reality that big packers retaliate against any chains that buy beef from independent producers.

— Peter S. Goodman (@petersgoodman) January 3, 2022

That doesn’t mean inflation is going to keep rising, only that concentration means that price signals are less responsive to underlying supply and demand. Tommaso Valletti, formerly top economist at the EU Competition Authority, noted that there are likely impacts on inflation of competition – the more competition the more quickly prices adjust.

Also, more competition implies more frequent price adjustments.

See e.g. work on exchange rates across sectors by @GitaGopinath & Itskhoki (QJE 2010), or by @CGenakos & Pagliero (AEJ: Applied, forthcoming) on excise taxes and cost of petrol in islands (literally).

3/ pic.twitter.com/O3nJ0ZbOcK— Tommaso Valletti (@TomValletti) January 5, 2022

This makes sense, and it’s consistent with what is happening in the ammunition market. Vista executives are trying to stop price adjustments downward by controlling output.

Still, the problem of market power hasn’t penetrated the world of macro-economists trying to understand price adjustments. When economists say that inflation is unrelated to market power, what they really mean is that they don’t have models of inflation that incorporate market power. Market power isn’t under the lamp post, so it must not matter.

But of course, that’s ridiculous. It does matter. The only question is, how much?

* * *

Welcome to BIG, a newsletter on the politics of monopoly power. If you’d like to sign up to receive issues over email, you can do so here.

Tyler Durden

Fri, 01/07/2022 – 23:20

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3F6ykkF Tyler Durden