Yen At Risk Of “Explosive” Downward Spiral With Kuroda Trapped… And Why China May Soon Devalue

The yen’s recent nosedive has heightened fears of a vicious cycle as Japan’s worsening current-account balance threatens to spur more selling while the BOJ’s dovish scramble to prevent rates from blowing out means that even modest countertrend buying will promptly reverse.

While a soft yen has long been seen as a boon to Japan’s economy, not to mention the stock market, and was one of the key drivers behind the launch of Abenomics whose anchor pillar was printing ginormous amounts of yen (and monetizing just as massive amounts of JGBs to monetize Japan’s prodigious deficit), now that benefits have tilted toward certain exporters and the wealthy while individuals and small businesses feel the pain of higher commodity prices, Japan may need to rethink a fundamental assumption of its economic approach.

After touching 125.1 to the dollar on Monday – its weakest point since August 2015 and approaching that year’s nadir of 125.86 – the yen rebounded slightly in volatile trading Tuesday to about 123 to 124 in Tokyo. According to Nikkei Asia, an estimate of the yen’s theoretical value may have fallen beyond 120 to the greenback, pointing to deeper problems than short-term speculation.

The immediate cause of the yen’s weakness has been a split in monetary policy between Japan and the U.S., with the BOJ re-emphasizing its commitment to super-loose policy as 10Y JGB yields nearly tripped 0.25%, the upper boundary of its Yield Curve Control corridor. If rise above, the central bank’s credibility in the bond market would be crushed. As a result, the Bank of Japan on Monday and Tuesday offered to buy unlimited amounts of Japanese government bonds to tamp down interest rates at a time when U.S. Treasury yields have soared as the Federal Reserve tightens policy to rein in inflation, encouraging traders to sell yen for dollars. Whereas on previous occasions the mere threat of buying debt was sufficient, this time the central bank found willing sellers to the tune of roughly $4 billion, also a first. Then on Wednesday, it unexpectedly offered to buy bonds in an unscheduled market operation.

But the softening trend in yen began before that, rooted in the more fundamental issue of Japan’s changing trade position.

As Nikkei report, in January, Japan’s current-account deficit topped 1 trillion yen ($8 billion). Imports in value terms have been ballooning amid coronavirus-related supply constraints and a commodities rally fueled by the war in Ukraine. Japan’s terms of trade, or the ratio between its export and import prices, have deteriorated, and more of the country’s income has flowed overseas as import costs have swelled.

These factors affect the underlying value of the yen.

The Nikkei equilibrium exchange rate calculated by Nikkei and the Japan Center for Economic Research stood at 105.4 yen to the dollar in the third quarter of 2021. Adjusting for shifts in Japan’s current-account balance and terms of trade since then puts the equilibrium rate at 121.7.

Market exchange rates often differ from the theoretical figure, reflecting short-term speculative trading and day-to-day conditions. Based on the average deviation between past equilibrium and market rates, the yen still has room to soften to about 130 against the dollar.

What is more, there remains a risk that Japan’s worsening current-account balance and terms of trade could bring on more yen selling in a vicious cycle.

Importers selling yen for dollar funds is “a root cause of the yen’s accelerating depreciation,” a bank executive tole Nikkei. A weaker currency in turn drives up the cost of imports in yen terms, which can further widen the current-account deficit. Worse terms of trade also make Japanese companies less competitive and add to the downward pressure on the yen.

BOJ governor Kuroda has stressed that the central bank has not changed its basic position that a weak yen is favorable for Japan’s economy and prices. But – as we have said since 2012 when the BOJ launched its latest and greatest monetary debasement experiment – the benefits tend to go mainly to a few exporters and affluent individuals with overseas assets. The vast majority of people and smaller businesses are likely to feel the pinch, and a yen-depreciation spiral would aggravate the pain.

Recent Japanese economic policy – particularly the catastrophic Abenomics policy of the now former prime minister – has centered on boosting corporate profits via a weak yen and waiting for the benefits to trickle down to households. But this approach has been a disaster in bringing meaningful wage growth, just as we said it would be.

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida seeks to tackle rising prices with measures including extending fuel subsidies, an approach criticized by some analysts.

“It’s just treating the symptoms,” said Tohru Sasaki, head of Japan market research at JPMorgan Chase Bank in Tokyo. “Simple fiscal expansion while the BOJ continues to buy government bonds could bring on more depreciation.”

In a recent note published by SocGen’s resident skeptic Albert Edwards and titled “Something huge is happening in FX world, and it’s not the dollar” (available to pro subs in the usual place), the strategist writes that “despite core CPI inflation surging in the US and the eurozone, Japan remains locked in deflation with core CPI there (excluding fresh food and energy) falling 1.0% yoy” and he observes that “surging commodity prices just do not seem to have the impact in Japan that they do in the west” (another SocGen strategist, Kit Juckes, thinks he may have found an explanation why with the BoJ publishing a paper this week on the topic of the contrasting Phillips Curves in the US and Japan – link.)

Albert then goes on to note that by capping the 10y JGB at 0.25% the BoJ has committed itself to unlimited intervention – and if yields continue to rise elsewhere, that will likely accelerate QE to pin JGB 10y yields at 0.25% (now 0.23% after rising as high as 0.248%). “The further widening of the yield spread and QE/QT contrast with the US can only weigh heavily on the yen” he notes.

What does this mean in pratical terms? Well, since Japan is the one country where rates are never allowed to normalize – since the country has so much accumulated sovereign debt even a modest rise in rates would lead to an instant debt crisis – at a time when other central banks are tightening more aggressively in a tacit acknowledgement that rising bond yields reflect valid inflation concerns, “the BoJ may perversely be forced to accelerate QE as JGB yields attempt to rise above 0.25%. It’s a strange world” as Edwards puts it.

And this is where the second massive implication of the BoJ relative easing of policy comes in. Extending on this article, Edwards warns that “as the yen declines, the trend becomes a self-perpetuating phenomenon known as the ‘carry trade’ where participants actively borrow in a depreciating yen to fund higher yielding investments abroad. The appetite for such trades increases markedly when – as last week – the yen breaks below key support levels and begins to decline sharply: in short, the fundamentals combine with the technical, leading to an explosive expansion of the carry trade.”

We have seen this before, most notably in the years before the Global Financial Crisis. Typically, the cheap yen funds are invested into similar instruments like higher yielding US Treasuries but as risk appetites mount, this extends into whatever momentum trade is dominant at the time. That may be commodities or it may be equities. Of course, ultimately it ends in tears (as it did in 2008 when it unwound), but as this new carry trade re-emerges, it means that the yen could fall an awfully long way from here – the ramifications of this might surprise investors.

So are we about to see another roll of the dice in Japan embracing (by default) another period of super-loose yen policy, Edwards asks. This effectively would mean that Japan is willing to soak up the west’s runaway inflation via higher import prices in the hope of kickstarting that wage / price spiral that (as we correctly predicted) never materialized in 2013 onwards. Or as the SocGen strategist rhetorically puts it:

Can a surge in Japan’s headline CPI this time around break the entrenched deflationary psychology of Japanese households? We’ll see.

We, for one, doubt it. Japan, as the premier exhibit of the insanity that is MMT, is coming to its inevitably monetary collapse. Which also means that the yen will drop much, much lower. Edwards agrees, and writes that “despite the yen being undervalued and over-sold, it is entirely plausible that it could fall a long way from here as traders get the bit between their teeth. Is Y150/$ possible? It is, because when the yen breaks, it moves sharply (eg in 2013 from 80 to 100, and again in 2015 from 100 to 120).”

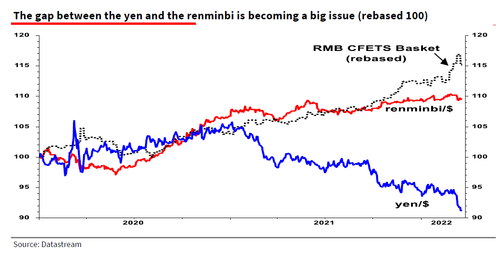

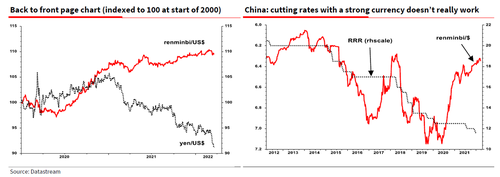

But while Japan may be a lost cause, a bigger question emerges: how will Japan’s latest devaluation impact its fellow exporting powerhouse competitors, i.e., China, and as Edwards frames it, “this beggars the question how will China react? Maybe just like they did in August 2015 when the PBoC devalued? Back then persistent yen weakness had dragged down other competing regional currencies and left the renminbi overvalued.”

Wait, yen weakness leading to China devaluation? According to Edwards, that indeed was the sequnece: as he shows in the chart below, the super weak yen of 2013-15, by driving down other competing Asian currencies, ultimately led us to the August 2015 renminbi devaluation.

Fast forward to today when the aggressive relative easing of the BoJ comes at a time when the PBoC also sticks out as a central bank unwilling to join the global tightening posture and instead is shifting towards an easier stance (after all, China has an imploding property sector it must stabilize at any cost).

Edwards concludes that the one thing to watch out for, especially in the current febrile geopolitical environment, is if China once again is ‘forced’ to devalue because of the weak yen. Economists will tell you that cutting interest rates or the reserve requirement ratio (RRR- r/h chart below) is neutralized when you have a strong currency.

Albert’s last word: “watch the renminbi – and watch the BoJ – whose lack of action is just as important as the Fed’s actions.”

More in Albert’s full note available to pro subs in the usual place.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 03/30/2022 – 15:08

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/Yc1U4J0 Tyler Durden