Morgan Stanley: Market Participants Do Not Appreciate The Implications Of New Capital Requirements

By Vishwanath Tirupattur, global head of Quantitative Research at Morgan Stanley

The Coming Capital Crunch

As macro strategists, digging deep into company earnings is outside our jurisdiction. We rely on our sector analysts for nuggets of information that could matter for fixed income markets. Insights from Betsy Graseck, our banks and consumer finance equity analyst, on the back of 2Q bank earnings highlight the impact of changes to regulatory capital requirements this year. These changes not only affect banks’ ability to buy back stock or pay dividends but are also likely to have a bearing on credit formation, credit spreads, and demand for high-quality assets on bank balance sheets, issues that are relevant for risk markets in general and fixed income markets in particular. In our view, market participants do not fully appreciate the implications of the new capital requirements.

A quick detour to frame why this is a big deal. As every investor knows, interest rates have risen sharply since the start of the year, which has meant that, like other investors, banks have had to write down the fixed-rate securities in their portfolios. This happens in every sell-off in rates, but this one was larger and faster than most. The move in five-year notes was the second-largest six-month sell-off in the last 30 years. The magnitude of the write-downs (especially combined with the spread widening in both mortgage and credit instruments) was large to say the least. Consequently, banks have less GAAP capital than normal, and the biggest banks have less regulatory capital too. That would be regrettable, but manageable.

But starting in January 2022, banks had to adopt a new approach (the Standard Approach to Counterparty Credit Risk or SACCR) to measure the counterparty risk of “off-balance sheet” derivatives. Under the Basel III rules, banks apply weights to assets based on riskiness, resulting in risk-weighted assets (RWA) against which they are assessed a capital charge. Government-guaranteed assets like cash, Treasuries, and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) guaranteed by Ginnie Mae have a 0% risk weight, hence there is no capital charge against them for this purpose. MBS issued by government-sponsored entities (GSEs) such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and general obligation municipal bonds carry a 20% risk weight, and most residential mortgage loans have a 50% weight. For most banks, SACCR increased the RWAs associated with derivatives contracts.

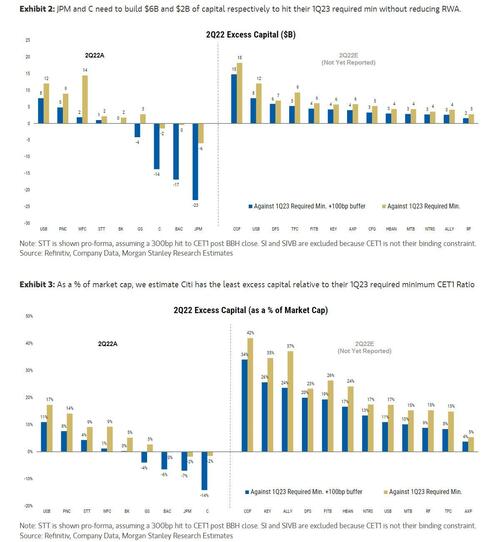

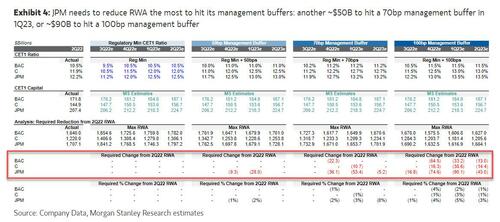

Beyond the capital impairment they faced from the sell-off in rates, credit spread widening, and the adoption of SAACR, banks must contend with the annual stress capital buffer (SCB) tests. The most recent results from these tests, released at the end of June, point to higher required regulatory capital than consensus expectations for some of the largest banks in the country, especially the money center banks. Add in the fact that several Globally Systemically Important Banks (GSIBs) will have an increase in their GSIB surcharge in 1Q23 and are actively working to reduce it by the end of 2022, and the largest banks in the US banking system are confronted with a serious challenge. Betsy notes that they will need to keep dividends flat, eliminate buybacks, and reduce their RWAs to generate a capital ratio above their new required minimums. She further estimates that the three largest banks (JPMorgan, Bank of America and Citigroup) alone will need to lower their RWAs by more than US$150 billion in aggregate by the end of the year if they maintain a 100bp management buffer on top of their regulatory capital minimums. While managements may choose to flex to a lower 50bp buffer, the market doesn’t stand still; higher volatility, higher equity market valuations, and growing loan books add to RWA balances.

In post-2Q earnings conference calls, different banks talked about “optimizing RWAs” and “RWA management”. What could that entail and what are the potential consequences? For starters, banks could move out of 20% risk assets such as Fannie/Freddie MBS and into 0% assets like Ginnie MBS. Bank of America and Wells Fargo announced that they are doing precisely that. We think that they don’t have enough of such assets in their portfolios currently to sufficiently reduce their RWAs. Banks have been substantial buyers of senior tranches of securitized products, thus playing a crucial role in enabling credit formation across a wide range of assets by providing senior leverage. While such senior tranches are risk-remote by construction, they carry higher risk weights and thus are capital intensive. If banks step back from such assets, the cost of financing would increase, affecting the cost and availability of credit across the system. Spreads of Fannie/Freddie MBS and CLO AAA tranches, trading near post-GFC wides, suggest that the pressures from RWA optimization are already at play. Furthermore, banks would need to reduce their footprint in trading and in their portfolio assets with higher RWAs, which could well impact market liquidity for those assets.

But, in the banks’ RWA, the biggest line item by far is their loan portfolio. Regulatory capital pressures mean that banks will increasingly have to make tough choices in their lending books. Citizens Financial highlighted that it is leaning into credit card, commercial and industrial, and home equity loans and away from mortgage, auto and education refinancing. The CFO of Citigroup noted on an investor conference call that the bank is requiring some of its least profitable trading clients to post more collateral and is even dropping some of them to help boost returns in its markets business. Betsy estimates that JPMorgan needs to reduce RWA by another ~US$90 billion by 1Q23 to get to its required capital ratios with a 100bp buffer, or US$28 billion with a 50bp buffer. JPMorgan indicated that it would distinguish between franchise and non-franchise lending and reduce the latter. Clearly, different banks will react differently to RWA pressures, but in aggregate we will likely see lower overall liquidity, lower credit formation, and continued pressure on spreads on capital-intensive assets.

In our view, market participants have yet to fully appreciate the challenges from the regulatory capital pressures on banks, particularly large-cap banks. These challenges are unlikely to dissipate within the next 2-3 quarters and add to the many other uncertainties markets are facing. If there is a silver lining, it is that, longer term, there may be better holders of the RWAs – entities that do not have the same capital pressures (e.g., sovereign wealth funds, pension funds and certain non-US banks) and may find these assets attractive additions to their portfolios.

Tyler Durden

Sun, 07/31/2022 – 13:30

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/sI8umSJ Tyler Durden