Want To Forecast Inflation? Don’t Track Breakevens

Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

Inflation breakevens – the difference between nominal and real yields – are an inadequate measure of future price growth, and long-term inflation is likely to be higher than they currently imply.

The biggest story for markets in this cycle is the path of inflation. Get that right, and many other investment questions become much easier to answer. According to breakevens, inflation will soon return to a low-and-stable regime.

But they are an empirically poor predictor of future inflation. In fact, a deeper look at how they are constructed and traded shows why we should not expect them to be an accurate forecast. Longer-term inflation is likely to be higher than breakevens anticipate.

Ultimately – and the clue’s in the name – breakevens are the rate needed to break even between a long TIPS position and a short US Treasury position. Functionally they are no different from the implied future FX spot rate based on FX forwards. No-one in markets would credibly claim the FX forward rate is an actual forecast of where the spot FX rate is likely to be.

But breakevens are believed to be somehow magically imbued with an ability to see far into the inflationary future. That is unfounded, however, and they often over or undershoot actual consumer inflation.

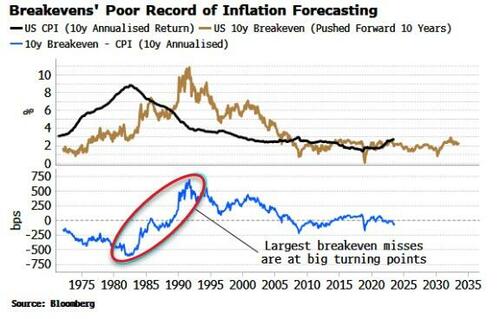

The chart below shows the 10y breakeven rate pushed forward 10 years, such that it lines up with 10y annualized CPI (the rate it’s supposed to predict), while the bottom panel shows how far the two deviate. In recent years, the gap has reduced, but that’s partly a scaling issue as the magnitude of the miss was so large in the 1970s and 1980s.

Those decades were – like now – major turning points for inflation, and it was then that breakevens were most wrong.

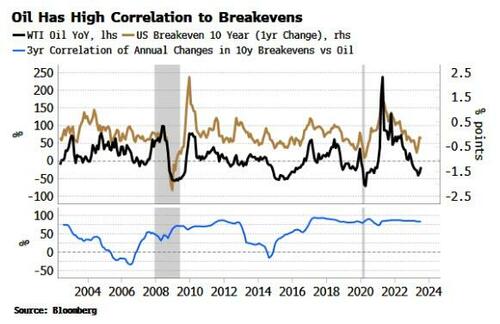

To see why, we have to bring in oil. It has a very high correlation to breakevens, much more than would be expected just based on its direct influence on inflation.

The strong relationship stems from the two markets feeding off each other. Oil is typically used as a hedge by commodity traders. Then as oil rises, inflation traders bid up TIPS, pushing real yields lower and thus breakevens higher.

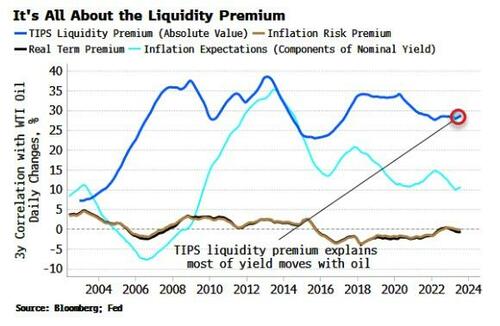

But despite the rise in breakevens, the main driver here is not an ex ante change in inflation expectations. To understand why, we use the DKW model (explained in this Fed paper) to decompose real and nominal yields. Nominal yields are set equal to real yields + expected inflation + inflation risk premium; and real yields are set to equal the expected real-short interest-rate + real term premium.

The real yield is not simply the yield on a TIPS bond, but instead the TIPS yield = real yield + the TIPS liquidity premium. So the TIPS yield has two moving parts, the “actual” real yield, and a liquidity premium for holding TIPS bonds. The inflation compensation can then be shown to be expected inflation + the inflation risk premium (IRP) – the TIPS liquidity premium.

The lay assumption made is that breakevens are just the first two terms but, as we can see from the chart below, when the oil price and yields move, the single biggest explanatory factor is the TIPS liquidity premium, not inflation expectations or the IRP. (Note, in the chart the absolute value has been taken with the TIPS liquidity-premium correlation, i.e. the actual correlation is negative).

This is significant as it tells us it is possible for inflation breakevens to widen even though there has been no underlying change in inflation expectations. When rising oil prices trigger a rise in breakeven rates, most of the variance in the move is explained by the liquidity premium – which falls as demand for TIPS rises from hedging activity – not principally due to a change in inflation expectations.

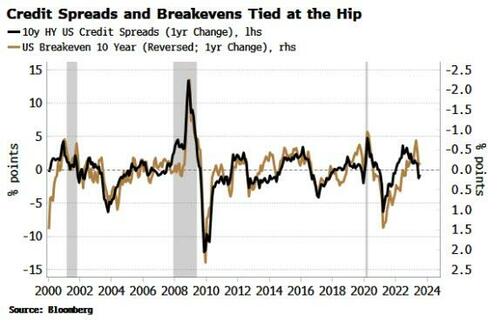

The role of the TIPS liquidity premium throws light on another relationship that would otherwise be somewhat mystifying: the almost preternaturally high correlation between breakevens and high-yield credit spreads. As the chart below shows, rises in breakevens and tightenings in credit spreads (and vice versa) move almost in lockstep.

Here again, the move in credit spreads is most sensitive to the TIPS liquidity premium. In other words, spreads are more responsive to a liquidity-premium-driven fall in real yields than one driven by an excessive rise in inflation.

That we don’t see as high a correlation between breakevens and investment-grade credit spreads suggests that higher-beta HY spreads benefit more when real yields fall in a less inflationary way, as well as benefiting from a general compression of risk premia that can occur alongside the fall in the TIPS liquidity premium.

None of this is to say breakevens have no inflation-forecasting utility at all; they do. But an understanding of their underlying drivers shows that they are typically not principally driven by ex ante changes in inflation views.

If you wish to be alert for signs of a re-acceleration in price growth, there are several places to look. But skip breakevens. By the time they rise it’ll be too late, as stocks and bonds will already be pricing in the new higher-inflation reality.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 08/15/2023 – 11:25

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/HZN8dQy Tyler Durden