China’s Foreign Direct Investment Turns Negative For The First Time On Record

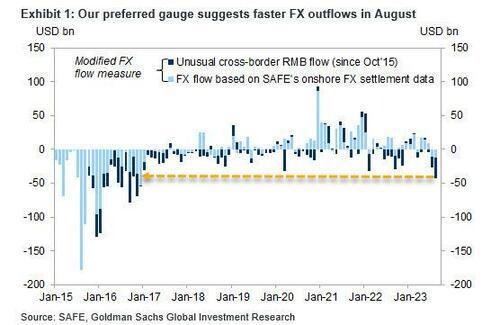

We got an early look that something is very broken in China’s capital flows back mid-September, when we first reported that contrary to the official PBOC forex data, a more in depth analysis of China’s fund flows reveals the biggest FX outflow since 2016 amid what we called was a “sudden surge in capital flight”, one which also kicked in just before bitcoin’s powerful thrust higher from $26K to $35K.

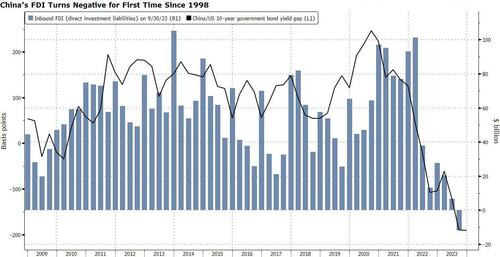

In retrospect, the reading wasn’t a fluke, and three months after we reported that “China’s Inward Foreign Direct Investment Falls To The Lowest Level On Record” the latest balance of payments data revealed that China recorded its first-ever quarterly decline in foreign direct investment (FDI), underscoring the capital outflow pressure we first flagged two months ago (and which was much more acute than the modest FX outflow signaled by the PBOC), and Beijing’s challenge in wooing overseas companies and capital in the wake of a “de-risking” move by Western governments.

As shown in the chart below, direct investment liabilities in the country’s balance of payments – a broad measure of FDI that includes foreign companies’ retained earnings in China – have been slowing over the last two years after hitting a near-peak value of more than $101 billion in the first quarter of 2022; since then the gauge weakened nearly every quarter and was a deficit of $11.8 billion during the July-September period, marking the first contraction since records started in 1998, which could be linked to the impact of “de-risking” by Western countries from China, as well as China’s interest rate disadvantage (the chart below shows a striking correlation between inbound FDI and China’s tumbling bond yields).

“It’s concerning to see net outflows where China’s doing its best at the moment to try and open — certainly the manufacturing sector — to new inflows,” said Robert Carnell, regional head of research for Asia-Pacific at ING Groep NV. “Maybe this is the beginning of a sign that people are just increasingly looking at alternatives to China for investment.”

“Some of the weakness in China’s inward FDI may be due to multinational companies repatriating earnings,” Goldman analyst Hui Shan wrote (full note available to pro subscribers) adding that “with interest rates in China ‘lower for longer’ while interest rates outside of China ‘higher for longer’, capital outflow pressures are likely to persist.”

According to Julian Evans-Pritchard, head of China economics at Capital Economics, the unusually-large interest rate gap “has led firms to remit their retained earnings out of the country”.

Although he sees little evidence that foreign companies are, on aggregate, reducing their presence in China, “we do think that, over the medium-term at least, increasing geopolitical tensions will hamper China’s ability to attract FDI and instead favor emerging markets that are more friendly to the West.”

Driven by the FDI outflows, China’s basic balance – which encompasses current account and direct investment balances and are more stable than volatile portfolio investments – recorded a deficit of $3.2 billion, the second quarterly shortfall on record.

“Given these unfolding dynamics, which are poised to exert pressure on the RMB, we anticipate a sustained strategic response from China’s authorities,” Tommy Xie, head of Greater China Research at OCBC wrote, and while he is hardly alone in expecting a powerful response from Beijing to stop the bleeding before China is fully “Japanified” so far the ruling Communist Party has failed to materially stimulate its economy, the result of a staggering 300% in consolidated debt to GDP, which has largely tied Beijing’s hand for the past 4 years.

Xie expects China’s central bank to continue counter-cyclical interventions – including a strong bias in daily yuan fixings and managing yuan liquidity in the offshore market- to support the currency in the face of these headwinds.

Separately, onshore yuan trading against the dollar also hit record-low volume in October, highlighting authorities’ stepped-up efforts to curb yuan selling. The latest data showed that onshore volume of yuan trading against the dollar slumped to a record low of 1.85 trillion yuan ($254.05 billion) in October, a 73% drop from the August level.

The PBOC has been urging major banks to limit trading and dissuade clients to exchange the yuan for the dollar, sources have told Reuters. This happened after our September report that FX outflows from China had hit $75 billion, the highest since the country’s 2015 devaluation.

In an attempt to reverse the bleeding, the Chinese government has embarked on a big push in recent months to lure foreign investment back to the country. Bloomberg reported that on Wednesday, the Ministry of Commerce asked local governments to clear discriminatory policies facing foreign companies in a bid to stabilize investment confidence. It’s doubtful the move will have any impact on capital flows which are not driven by “discriminatory” policies and have everything to do with China’s dismal economy.

It cited the need to ensure subsidies for new energy vehicles are not limited to domestic brands as one example. In some industries, foreign firms wait longer and are subject to more rigorous reviewing process when applying for licenses.

In August, the internet regulator met with executives from dozens of international firms to ease concerns about new data rules. The government has also pledged to offer overseas companies better tax treatment and make it easier for them to obtain visas.

But Beijing’s pledges have rung hollow for some firms, with foreign business groups decrying “promise fatigue” amid skepticism about whether meaningful policy support is forthcoming. They also have incentive to repatriate earnings overseas because of the wide gap in interest rates between China and the US, which may be pushing them to seek higher returns elsewhere.

The FDI outflows are adding pressure on the onshore yuan, which has hit the weakest level since 2007 earlier this year. China’s benchmark 10-year government bond yield is trading at 191 basis points below that of comparable US Treasuries, versus an average premium of about 100 basis points over the past decade.

The lack of investment among global firms in China will have far reaching effects on the world’s second-largest economy, especially as it tries counter US curbs on access to advanced technology.

Aside from geopolitical risks, companies had also been pulling back on investment in China last year as the country rolled out pandemic restrictions. While those curbs have been removed, firms are still contending with other challenges from rising manufacturing costs in China and regulatory hurdles as Beijing scrutinizes activity at foreign corporations due to national security concerns.

“Some of the most damaging things have been the abrupt regulatory changes that have taken place,” said Carnell, pointing to this year’s anti-espionage campaign, which resulted in some firms having their offices raided by local authorities. “Once you damage the sort of perception of the business environment, it’s quite difficult to restore trust. I think it will take some time.”

While foreign companies make up less than 3% of the total number of corporations in China, they contribute to 40% of its trade, more than 16% of tax revenue and almost 10% of urban employment, state media has reported. They’ve also been key to China’s technological development, with foreign investment in the country’s high-tech industry growing at double-digit rates on average since 2012, according to the official Xinhua News Agency.

“A decline in trade and investment links with advanced economies will be a particularly significant headwind for a catching up economy such as China, weighing on productivity growth and technological progress,” Kuijs said. And since youth unemployment – the single, most direct precursor to the one thing Beijing fears most of all, social unrest – is already at an all time high and will continue to rise (even if China will no longer report on what it is), the likelihood that Beijing will pursue some bazooka stimulus, both fiscal and monetary, only grows with every month that Beijing does not pursue such a critical, if temporary, measure to prevent catastrophe.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 11/08/2023 – 18:00

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/PdFJVpT Tyler Durden