Submitted by Gail Tverberg of Our Finite World blog,

If oil is “just another commodity,” then there shouldn’t be any connection between oil prices, debt levels, interest rates, and total rates of return. But there clearly is a connection.

On one hand, spikes in oil prices are connected with recessions. According to economist James Hamilton, ten out of eleven post-World War II recessions have been associated with spikes in oil prices. There also is a logical reason for oil prices spikes to be associated with recession: oil is used in making and transporting food, and in commuting to work. These are necessities for most people. If these costs rise, there is a need to cut back on non-essential goods, leading to layoffs in discretionary sectors, and thus recession.

On the other hand, the manipulation of interest rates and the addition of governmental debt (by spending more than is collected in tax dollars) are the primary ways of “fixing” recession. According to Keynesian economics, output is strongly influenced by aggregate demand–in other words, total spending in the economy. Any approach that can increase total spending–either more debt, or more affordable debt will increase economic output.

What is the Direct Connection Between Increased Debt and Oil Prices?

The economy doesn’t just grow by itself (contrary to the belief of many economists). It grows because affordable energy products allow raw materials to be transformed into finished products. Increased debt helps energy products become more affordable.

Figure 1.

Without debt, not a very large share of the total population could afford a car or a new home. In fact, most businesses could not afford new factories, without debt. The price of commodities of all sorts would drop off dramatically without the availability of debt, because there would be less demand for the commodities that are used go make goods.

With commodities, such as oil or copper, there is a two way pull:

- The amount it costs to extract the oil or copper (including taxes, shipping costs, and other indirect costs), and

- The selling price for the commodity. The selling price reflects the customers’ ability to pay for the product, based on wages and debt availability. It also reflects other issues, such as the availability of cheaper substitutes.

The availability of increased cheap debt tends to pull oil (and copper and other commodity) prices high enough that businesses find it profitable to extract these commodities. This is why Keynesian economics tends to work–at least historically. When oil prices dropped to the low $30s barrel in 2008, the issue was very much a “decrease in debt outstanding” problem–taking place even before the Lehman bankruptcy–as I will show in later charts.

Figure 2. Oil price based on EIA data with oval pointing out the drop in oil prices, with a drop in credit outstanding.

The peak in oil prices took place in July 2008. When we look at US mortgage amounts outstanding, we find that home mortgage debt hit a peak on March 31, 2008, and very slightly declined by June 30, 2008. The bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers did not take place until September 15, 2008. A further decline in the amount of home mortgages outstanding occurred from that point on, partly because of declining sales prices and partly because commercial organizations bought homes to rent them out.

Figure 3. US home mortgage debt, based on Federal Reserve Z.1 data

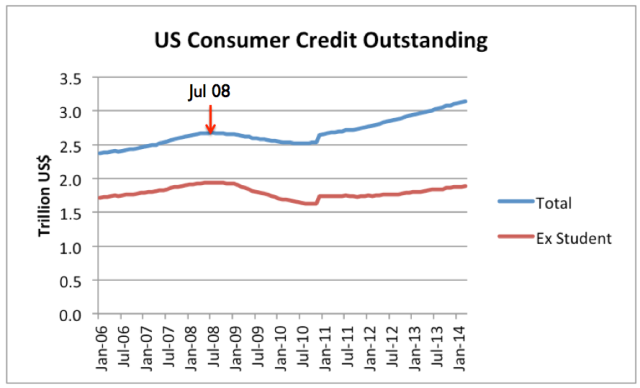

When we look at consumer credit outstanding, we find that consumer credit outstanding hit a maximum on July 31, 2008, and began declining by August 31, 2008. (Consumer credit is available monthly, while mortgage debt is available only quarterly. Some definitional change regarding consumer credit must have taken place as of December 31, 2010, to cause the jump in amounts in the graph.)

FIgure 4. Consumer Credit Outstanding based on Federal Reserve Data. Student Loan data was available only for 12/31/2008 and subsequent. Prior amounts were estimated.

When student loans are excluded, consumer credit outstanding (including such items as credit card debt and auto loans) is still not back up to the July 31, 2008 level today (Figure 4).

I have not shown commercial and financial debt, but they decreased as well, with somewhat later peak dates, coinciding more with the Leyman collapse. In my view, the spending of individual citizens is primary. When their spending falls, it quickly ripples through to business and government accounts. We see this affect slightly later.

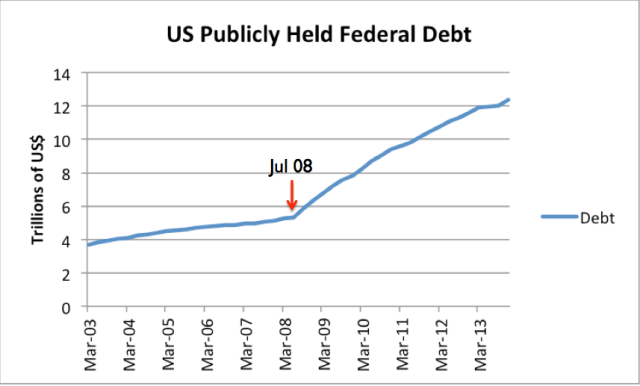

The Federal Government quickly stepped in with more spending (funded by debt), as shown in Figure 5, below.

Figure 5. U S publicly held federal government debt, based on Federal Reserve data.

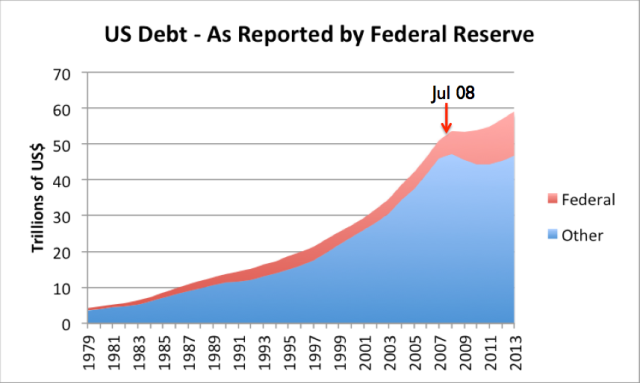

If we combine all United States debt (Figure 6, below), including both government and non-government, it becomes clear that the rate of increase in debt slowed markedly in 2008 and subsequent years.

Figure 6. US debt, excluding debt which is owed to governmental agencies such as the Social Security Administration. Amounts based on Federal Reserve Z.1 data.

Without this increasing debt, oil prices dropped to less than one-fourth of their maximum values (Figure 2). Prices of other energy products–even uranium–dropped as well. Somehow the high prices of oil that occurred in early 2008 had turned off the “pump” of ever-increasing debt that had previously held up commodity prices.

Oil Prices and Interest Rates–the Two Big Factors Affecting Discretionary Income

If oil prices spike, clearly discretionary income falls, for reasons described above. If interest rates spike, suddenly goods that are bought with credit (such as automobiles, homes, and new factories) become more expensive. Thus, a spike in interest rates will tend to adversely affect discretionary income as well. If the Federal Reserve wants to counter high oil prices (which continue to affect discretionary income adversely for the long term), it needs to keep interest rates low. Hence, the attempts to keep interest rates low for the long term.

The primary approach to keeping interest rates low has been Quantitative Easing (QE).US QE was begun in late 2008 and has been kept in place since. Other major countries are also using QE to keep interest rates down. The hope is that with very low interest rates the economies can somehow recover.

QE Doesn’t Really Work, Because it Doesn’t Fix Wages, Which are the Underlying Problem

When oil prices are high, wages tend to stagnate (Figure 7, below).

Figure 7. Average US wages compared to oil price, both in 2012$. US Wages are from Bureau of Labor Statistics Table 2.1, adjusted to 2012 using CPI-Urban inflation. Oil prices are Brent equivalent in 2012$, from BP’s 2013 Statistical Review of World Energy.

The reason why wages tend to stagnate when oil prices are high has to do with the adverse impact high oil prices have on the economy. Consumers cut back on discretionary spending. This leads to a loss of jobs in discretionary sectors. Also, labor is one of the biggest costs most businesses have. If profits are squeezed by high oil prices, the logical response if to try to reduce wages in response. One way is to outsource production to a lower-wage country. Another is to mechanize the process more, thereby slightly increasing fuel usage but significantly decreasing wage costs.

Instead of going to individuals as wages, the money from QE seems to go to speculators, who use it to bid up stock prices and land prices. The money from QE also tends to hold home prices up, because some homes are purchase by speculators. The money from QE also helps encourage investment in marginal enterprises, such as in shale gas drilling. As a recent Bloomberg, described the situation, Shale Drillers Feast on Junk Debt to Stay on Treadmill.

What Really Pumps Up the Economy is a Rising Supply of Cheap Oil

One piece of evidence supporting the view that a rising supply of cheap oil pumps up the economy is the rising average wages seen in Figure 7 (above) during periods when oil prices are low. Another piece of evidence that this is the case is the close correlation between oil consumption (and energy consumption in general) and inflation-adjusted GDP (Figure 8, below).

Figure 8. Growth in world GDP, compared to growth in world of oil consumption and energy consumption, based on 3 year averages. Data from BP 2013 Statistical Review of World Energy and USDA compilation of World Real GDP.

When there is an inadequate supply of oil, it affects GDP growth. This happens because there is no inexpensive, quick way of switching away from oil. We need oil for very many uses, including transport, agriculture, and construction. In the late 70s and early 80s, we tried to switch away from oil as much as possible. Now the low-hanging fruit for making such a switch are mostly gone.

The spike in oil prices signaled that something had changed dramatically. We could no longer count on a rising supply of cheap oil to pump up the economy. People’s job opportunities were dropping. They found it necessary to cut back on debt. Either that, or creditors cut off credit availability. One way or another, citizens started using less debt.

World Oil Supply

World oil supply is growing only very slowly, as illustrated in Figure 9. While we hear much about the growth in oil from shale formations in the US, this is mostly acting to offset falling production elsewhere.

Figure 9. Growth in world oil supply, with fitted trend lines, based on BP 2013 Statistical Review of World Energy.

It is this lack of growth in oil supply together with the high price of oil that is holding back world economic growth. As stated previously, very low interest rates are needed to even maintain the level of economic growth we have now.

The Difference Between and Growing and Shrinking World Economy for Repaying Debt

In a growing economy, it is possible to repay debt with interest. But once an economy flattens, it is much harder to repay debt.

Figure 10. Repaying loans is easy in a growing economy, but much more difficult in a shrinking economy.

It is likely that it is this problem that underlies the difficulty economies have in increasing their indebtedness. Very low interest rates can help, but ultimately, if the economy is not expanding, debt doesn’t work well. Wages are not growing in inflation-adjusted terms, and because of this, it is not possible for citizens to take on much more debt. Increased student debt gets in the way of buying homes using mortgages later.

The Unfortunate Oil Price Problem We Have Now

The problem we have now is that a rising supply of cheap oil is no longer possible. Most of the cheap-to-extract oil is already gone.

Instead, the cost of extraction keeps rising, but wages are not going up enough for people to afford the high cost of extracting oil (even with super-low interest rates). The unfortunate outcome is that oil prices are now too low for many producers. I described this in my post, Beginning of the End? Oil Companies Cut Back on Spending.

Because oil prices are too low for companies doing the extraction, we really need higher oil prices. But if oil prices are higher, they will put the country (and the world) back into recession. Interest rates are already very low–it is not possible to lower them further to offset higher oil costs. We are reaching the edge of how much central banks can do to hold economies together.

The Effect of Rising Interest Rates on the Economy

If it takes very low interest rates to offset the impact of high oil prices, it should be clear that rising interest rates, if they ever should occur, will have a disastrous effect on the economy. If interest rates should rise, they could be expected to have a number of adverse effects, pretty much simultaneously.

- They make the monthly payments for a new home or new car higher, reducing the sales of both

- They reduce the sales price of existing bonds (carried on the books of banks, pension funds, and insurance companies)

- They likely will reduce stock market prices, because bonds will look like they will yield better in comparison.

- Also, the country will be shifted into recession, and lower stock prices will result based on the apparently worse prospects of most companies.

- The resale value of homes will likely drop, because fewer people will be in the market for a move-up home.

- The US government will need to pay higher interest on its debt, necessitating a rise in taxes, further pushing the country toward recession.

- With higher taxes and more layoffs, there will be more defaults on debts of all kinds. Banks, insurance companies, and pension plans will be especially affected. Many will need to be bailed out, but it will be increasingly difficult to do so.

The Federal Reserve has said that it is in the process of scaling back the amount of debt it buys under QE. The expected effect of scaling back QE is that interest rates will rise, especially at with respect to longer-term debt. For a while, US interest rates did rise, and home sales dropped off. But more recently in 2014 year to date, interest rates seem to be falling rather than rising. This is strange, since this is the period when the scaling back of QE is supposedly actually taking place, rather than just planned. It is possible that overseas transactions are distorting what is really happening.

Getting Out of this Mess

The substitution of debt for additional salary isn’t necessarily a very good one, even with very low interest rates. For example, the maximum length of new car loans has increased from five years to six years to seven years, allowing people to afford more expensive cars. The catch is that loans are “underwater” longer, and it becomes harder to buy a replacement car. So ultimately, buyers tend to keep their cars longer, reducing the demand for new cars. The problem isn’t entirely solved; to some extent it is just delayed.

It is hard to see a way out of our current predicament. The ability of consumers to pay higher prices for goods and services under normal circumstances requires higher wages. But if higher wages are not available, higher debt plus very low interest rates can “sort of” substitute. This cannot be a permanent solution, because there are too many things that will disturb this equilibrium.

As we have seen, rising interest rates will bring an end to our current equilibrium, by raising costs in many ways, without raising salaries. It will also reduce equity values and bond prices. A rise in the cost of extraction of oil, if it isn’t accompanied by high oil prices, will also put an end to our equilibrium, because oil producers will stop drilling the number of wells needed to keep production up. If oil prices rise (regardless of reason), this will tend to put the economy into recession, leading to job loss and debt defaults.

The only way to keep things going a bit longer might be negative interest rates. But even this seems “iffy.” We truly live in interesting times.

via Zero Hedge http://ift.tt/1n7jG0Q Tyler Durden