For all your, well just one really, New Normal daytrading needs.

courtesy of @Not_Jim_Cramer

![]()

via Zero Hedge http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/zerohedge/feed/~3/vhab-9dB35w/story01.htm Tyler Durden

another site

For all your, well just one really, New Normal daytrading needs.

courtesy of @Not_Jim_Cramer

![]()

via Zero Hedge http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/zerohedge/feed/~3/vhab-9dB35w/story01.htm Tyler Durden

Authored by John Taylor, originally posted at WSJ.com,

It is a common view that the shutdown, the debt-limit debacle and the repeated failure to enact entitlement and pro-growth tax reform reflect increased political polarization. I believe this gets the causality backward. Today’s governance failures are closely connected to economic policy changes, particularly those growing out of the 2008 financial crisis.

The crisis did not reflect some inherent defect of the market system that needed to be corrected, as many Americans have been led to believe. Rather it grew out of faulty government policies.

In the years leading up to the panic, mainly 2003-05, the Federal Reserve held interest rates excessively low compared with the monetary policy strategy of the 1980s and ’90s—a monetary strategy that had kept recessions mild. The Fed’s interest-rate policies exacerbated the housing boom and thus the ensuing bust. More generally, extremely low interest rates led individual and institutional investors to search for yield and to engage in excessive risk taking, as Geert Bekaert of Columbia University and his colleagues showed in a study published by the European Central Bank in July.

Meanwhile, regulators who were supposed to supervise large financial institutions, including Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, allowed large deviations from existing safety and soundness rules. In particular, regulators permitted high leverage ratios and investments in risky, mortgage-backed securities that also fed the housing boom.

After the housing bubble burst the value of mortgage-backed securities plummeted, putting the solvency of the many banks and other financial institutions at risk. The government stepped in, but its ad hoc bailout policy was on balance destabilizing.

Whether or not it was appropriate for the Federal Reserve to bail out the creditors of Bear Stearns in March 2008, it was a mistake not to lay out a framework for future interventions. Instead, investors assumed that the creditors of Lehman Brothers also would be bailed out—and when they weren’t and Lehman declared bankruptcy in September, it was a big surprise, raising grave uncertainty about government policy going forward.

The government then passed the Troubled Asset Relief Program which was supposed to prop up banks by purchasing some of their problematic assets. The purchase plan was viewed as unworkable and financial markets continued to plummet—the Dow fell by 2,399 points in the first eight trading days of October—until the plan was radically changed into a capital injection program. Former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, appearing last month on CNBC on the fifth anniversary of the Lehman bankruptcy, argued that TARP saved us. Former Wells Fargo CEO Dick Kovacevich, appearing later on the same show, argued that TARP significantly worsened the crisis by creating even more uncertainty.

In any case, the crisis ended, but rather than simply winding down its short-term liquidity facilities the Fed continued to intervene through massive asset purchases—commonly called quantitative easing. Many outside and inside the Fed are unconvinced quantitative easing is meeting its objective of spurring economic growth. Yet there is a growing worry about the Fed’s ability to reduce its asset purchases without market disruption. Bond and mortgage markets were roiled earlier this year by Chairman Ben Bernanke’s mere hint that the Fed might unwind.

The crisis ushered in the 2009 fiscal stimulus package and other interventions such as cash for clunkers and subsidies for first-time home buyers, which have not led to a sustained recovery. Crucially, the actions taken during the immediate crisis set a precedent for giving the federal government more power to intervene and regulate, which has added to uncertainty.

The Dodd-Frank Act, meant to promote financial stability, has called for hundreds of new rules and regulations, many still unwritten. The law was supposed to protect taxpayers from bailouts. Three years later it remains unclear how large complex financial institutions operating in many different countries will be “resolved” in a crisis. Any fear in the markets about whether a troubled big bank can be handled through Dodd-Frank’s orderly resolution authority can easily drive the U.S. Treasury to resort to another large-scale bailout.

Regulations and interventions also increased in other industries, most significantly in health care. The mandates at the core of the Affordable Care Act represent an unprecedented degree of control by the federal government of the activities of businesses and individuals, adversely affecting incentives to hire and work and eventually worsening the federal-budget outlook.

Federal debt held by the public has increased to 73% of GDP this year from 41% in 2008—and according to the Congressional Budget Office, it will rise to more than 250% without a change in policy. This raises uncertainty about how the debt can be brought under control.

Despite a massive onslaught of legislation and regulation designed to foster prosperity, economic growth remains low and unemployment remains high. Rhetoric aside, many both inside and outside the government quite reasonably seek to return to the kinds of policies that worked well in the not-so-distant past. Claiming that one political party has been hijacked by extremists misses this key point, and prevents a serious discussion of the fundamental changes in economic policies in recent years, and their effects.

![]()

via Zero Hedge http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/zerohedge/feed/~3/zN-oCk2HCjY/story01.htm Tyler Durden

Earlier this afternoon, it was Steve Cohen’s final fall from grace. Now, Bloomberg reports that Brazil’s one time super billionaire, and now negativeworthaire, Eike Batista, whose sprawling petroleum empire was once valued in the tens of billions, is set to file for bankruptcy tomorrow.

We are confident that just like in Europe, there is no bank with any exposure to either OGX, Brazil, or whatever potential intercreditor avalanche will tear down many more Brazilian companies once this first insolvent domino finally tips over.

Those who missed the preface to this story, we repost it below.

When on October 1, fallen billionaire Eike Batista’s OGX Petroleo & Gas, missed a $45 million bond coupon payment, some were surprised but most had seen the writing on the wall. After all, Brazil’s second largest oil company after Petrobras, and the crowning jewel of Batista’s EBX Group, had been under the microscope of investors and certainly creditors (and if it wasn’t it certainly should have been) after oil deposits that Batista had valued at $1 trillion turned out to be commercial failures. And so the countdown to the inevitable bankruptcy filing began. Overnight, Bloomberg reports that the wait should not be long (in fact it may coincide with the default of that other insolvent mega-creditor: the United States), and will mostly certainly take place before the end of the month, following the retention of bankruptcy specialist law firm Quinn Emanuel.

From Bloomberg:

Quinn Emanuel was hired to work on restructuring and potential litigation matters in the U.S. for Batista, said the people, who asked not to be named because they weren’t authorized to speak publicly.

OGX Petroleo & Gas Participacoes SA (OGXP3) is considering filing for bankruptcy protection by the end of this month, two people with direct knowledge of the matter said last week. The filing would be done in Rio de Janeiro where OGX is based, said the people, asking not to be identified as discussions are private. While Batista is negotiating with creditors to avoid the same process for shipbuilder OSX Brasil SA (OSXB3), the most likely outcome is that both companies will seek legal protection, they said.

Prior stakeholder representations by Quinn Emmanuel have been the bankruptcies of energy trader Enron Corp., futures trader Refco Inc. and oil-trader SemGroup LP, according to the firm’s website, so they are quite proficient at representing what is about to be Latin America’s largest energy-related bankruptcy in a long time.

And while it is unclear if the company will file concurrently in the US under Chapter 15, Batista’s creditors, awoken from their “all is well” slumber and scrambling, have decided to pull an Elliott management, and take possession of at least two ships used as collateral by another Batista company, shipbuilder OSX and sister company to OGX, whose assets may also be impaired as unknown cross-default provisions are triggered and a vicious intercreditor fight ensues.

Bloomberg reports that OSX Brasil bank creditors considering taking possession of 2 vessels used as collateral on loans to Batista’s shipbuilder, say 6 people with knowledge. The banks are talking to advisers and company officials to see if they should execute guarantees if OSX’s oil sister co. goes into default, which would trigger cross-default clauses on OSX. Bloomberg adds that OSX already hired Credit Suisse to help sell OSX-1, OSX-2 platforms that guarantee loans.

One question is what the waterfall effects on local banks would be in the case of a bankruptcy filing, due to massive exposure to the company by both local and foreign financial firms – case in point OSX borrowed $1.27 billion from banks including Santander, DVB and others. Naturally officials at neither DVB nor Santander commented.

Either way, the seemingly endless period of financial stability in Latin America, and particularly Brazil (where record consumer debt is a far greater issue), long seen as a derivative of China, is ending. Luckily, the next steps in the global overlevered soap opera are about to be unveiled. So sit back, grab the popcorn and watch as the world receives yet another Donald Trump, i.e., fallen billionaire angel, this time in Latin America, and all the associated entertainment, even if it is not quite as entertaining for the thousands of Brazilians who are about to lose their jobs as the debt tsunami finally rolls over.

![]()

via Zero Hedge http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/zerohedge/feed/~3/9CnS-zhMz_A/story01.htm Tyler Durden

Earlier this afternoon, it was Steve Cohen’s final fall from grace. Now, Bloomberg reports that Brazil’s one time super billionaire, and now negativeworthaire, Eike Batista, whose sprawling petroleum empire was once valued in the tens of billions, is set to file for bankruptcy tomorrow.

We are confident that just like in Europe, there is no bank with any exposure to either OGX, Brazil, or whatever potential intercreditor avalanche will tear down many more Brazilian companies once this first insolvent domino finally tips over.

Those who missed the preface to this story, we repost it below.

When on October 1, fallen billionaire Eike Batista’s OGX Petroleo & Gas, missed a $45 million bond coupon payment, some were surprised but most had seen the writing on the wall. After all, Brazil’s second largest oil company after Petrobras, and the crowning jewel of Batista’s EBX Group, had been under the microscope of investors and certainly creditors (and if it wasn’t it certainly should have been) after oil deposits that Batista had valued at $1 trillion turned out to be commercial failures. And so the countdown to the inevitable bankruptcy filing began. Overnight, Bloomberg reports that the wait should not be long (in fact it may coincide with the default of that other insolvent mega-creditor: the United States), and will mostly certainly take place before the end of the month, following the retention of bankruptcy specialist law firm Quinn Emanuel.

From Bloomberg:

Quinn Emanuel was hired to work on restructuring and potential litigation matters in the U.S. for Batista, said the people, who asked not to be named because they weren’t authorized to speak publicly.

OGX Petroleo & Gas Participacoes SA (OGXP3) is considering filing for bankruptcy protection by the end of this month, two people with direct knowledge of the matter said last week. The filing would be done in Rio de Janeiro where OGX is based, said the people, asking not to be identified as discussions are private. While Batista is negotiating with creditors to avoid the same process for shipbuilder OSX Brasil SA (OSXB3), the most likely outcome is that both companies will seek legal protection, they said.

Prior stakeholder representations by Quinn Emmanuel have been the bankruptcies of energy trader Enron Corp., futures trader Refco Inc. and oil-trader SemGroup LP, according to the firm’s website, so they are quite proficient at representing what is about to be Latin America’s largest energy-related bankruptcy in a long time.

And while it is unclear if the company will file concurrently in the US under Chapter 15, Batista’s creditors, awoken from their “all is well” slumber and scrambling, have decided to pull an Elliott management, and take possession of at least two ships used as collateral by another Batista company, shipbuilder OSX and sister company to OGX, whose assets may also be impaired as unknown cross-default provisions are triggered and a vicious intercreditor fight ensues.

Bloomberg reports that OSX Brasil bank creditors considering taking possession of 2 vessels used as collateral on loans to Batista’s shipbuilder, say 6 people with knowledge. The banks are talking to advisers and company officials to see if they should execute guarantees if OSX’s oil sister co. goes into default, which would trigger cross-default clauses on OSX. Bloomberg adds that OSX already hired Credit Suisse to help sell OSX-1, OSX-2 platforms that guarantee loans.

One question is what the waterfall effects on local banks would be in the case of a bankruptcy filing, due to massive exposure to the company by both local and foreign financial firms – case in point OSX borrowed $1.27 billion from banks including Santander, DVB and others. Naturally officials at neither DVB nor Santander commented.

Either way, the seemingly endless period of financial stability in Latin America, and particularly Brazil (where record consumer debt is a far greater issue), long seen as a derivative of China, is ending. Luckily, the next steps in the global overlevered soap opera are about to be unveiled. So sit back, grab the popcorn and watch as the world receives yet another Donald Trump, i.e., fallen billionaire angel, this time in Latin America, and all the associated entertainment, even if it is not quite as entertaining for the thousands of Brazilians who are about to lose their jobs as the debt tsunami finally rolls over.

![]()

via Zero Hedge http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/zerohedge/feed/~3/9CnS-zhMz_A/story01.htm Tyler Durden

The average life expectancy for a fiat currency is less than 40 years.

But what about “reserve currencies”, like the U.S. dollar?

JP Morgan noted last year that “reserve currencies” have a limited shelf-life:

As the table shows, U.S. reserve status has already lasted as long as Portugal and the Netherland’s reigns. It won’t happen tomorrow, or next week … but the end of the dollar’s rein is coming nonetheless, and China and many other countries are calling for a new reserve currency.

Remember, China is entering into more and more major deals with other countries to settle trades in Yuans, instead of dollars. This includes the European Union (the world’s largest economy).

And China is quietly becoming a gold superpower, and China has long been rumored to be converting the Yuan to a gold-backed currency.

But a switch to a totally-different system – say, a gold-backed yuan – would cause enormous disruption and chaos. China – which has been a long-term planner for thousands of years – doesn’t want such a sudden change.

Moreover, housing the world’s reserve currency is a huge burden, as well as a privilege. Venture Magazine notes:

The inherent burden of housing the world’s reserve currency is that the U.S. must continue to run a balance of payment deficit to meet the growing demand. However, it was this outstanding external debt that caused investors to lose confidence in the value of the reserve assets.

Michael Pettis – the well-known American economist teaching at Peking University in Beijing – explains:

A world without the dollar would mean faster growth and less debt for the United States, though at the expense of slower growth for parts of the rest of the world, especially Asia.

***

When foreigners actively buy dollar assets they force down the value of their currency against the dollar. U.S. manufacturers are thus penalized by the overvalued dollar and so must reduce production and fire American workers. The only way to prevent unemployment from rising then is for the United States to increase domestic demand — and with it domestic employment — by running up public or private debt. But, of course, an increase in debt is the same as a reduction in savings. If a rise in foreign savings is passed on to the United States by foreign accumulation of dollar assets, in other words, U.S. savings must decline. There is no other possibility.

***

By definition, any increase in net foreign purchases of U.S. dollar assets must be accompanied by an equivalent increase in the U.S. current account deficit. This is a well-known accounting identity found in every macroeconomics textbook. So if foreign central banks increase their currency intervention by buying more dollars, their trade surpluses necessarily rise along with the U.S. trade deficit. But if foreign purchases of dollar assets really result in lower U.S. interest rates, then it should hold that the higher a country’s current account deficit, the lower its interest rate should be.

Why? Because of the balancing effect: The net amount of foreign purchases of U.S. government bonds and other U.S. dollar assets is exactly equal to the current account deficit. More net foreign purchases is exactly the same as a wider trade deficit (or, more technically, a wider current account deficit).

So do bigger trade deficits really mean lower interest rates? Clearly not. The opposite is in fact far more likely to be true. Countries with balanced trade or trade surpluses tend to enjoy lower interest rates on average than countries with large current account deficits — which are handicapped by slower growth and higher debt.

The United States, it turns out, does not need foreign purchases of government bonds to keep interest rates low any more than it needs a large trade deficit to keep interest rates low. Unless the United States were starved for capital, savings and investment would balance just as easily without a trade deficit as with one.

***

Only the U.S. economy and financial system are large enough, open enough, and flexible enough to accommodate large trade deficits. But that badge of honor comes at a real cost to the long-term growth of the domestic economy and its ability to manage debt levels.

For the reasons outlined by Pettis, China – which has the world’s 2nd biggest economy (or 1st … depending on the measure used) – doesn’t want the burden of housing the world’s reserve currency.

As such, China is pushing for a basket of currencies to replace the dollar as reserve currency.

Indeed, China – as well as Russia, the U.N. and many other countries and agencies – have called for the “SDR” to become the new reserve currency. SDR stands for “Special Drawing Rights”, and it is a basket of 4 currencies – the US dollar

, Euro, British pound, and Japanese yen – administered by the International Monetary Fund.

Jim Rickards – one of the leading authorities on currency, having briefed the CIA, Pentagon and Congress on currency issues – says:

China is not buying gold to create a new gold standard; rather it is aiming to make the Yuan more attractive, with the end result of being included in a basket of currencies, referred to as the Special Drawing Rate (SDR). He added that there is a move to make the SDR the new global reserve currency.

“Everybody knows that the U.S. dollar’s days are numbered but there is no really currency to take its place except for the SDR,” he said.

“What the world is trying to do is move to the SDR and China is fine with that.”

Rickards added that China’s goal of being in an SDR basket is the best of both worlds; the country can still have total control over its monetary policy and capital accounts but still influence global economics by being part of a basket of currencies.

“What the Chinese want is to have the Yuan in the SDR basket but not open up their capital account,” he said. “That is a backdoor way for the Yuan to be a de facto reserve currency without having to give up control.”

It is silly to exclude the Yuan from the basket of currencies.

Indeed, given that there are privileges and burdens of having the reserve currency, I would argue that – if we are going to move away from the dollar as sole reserve currency – all of the currencies of the world could be in the basket … in proportion to the size of their economies. It is simple to look up the GDP of the world’s nations.

That way, each country would all share in the benefits and costs, in proportion to its size and strength.

(Obviously, some countries have such small or unstable economies that no one would want to settle in their currency. To be realistic, they’d probably be dropped out of the basket. But the ideal of including everyone is worth maintaining.)

While having a basket of different things acting as the world’s reserve currency may sound like a new idea, John Maynard Keynes – creator of our modern “liberal” economics in the 1930s – promoted a basket of 30 commodities called the “Bancor” to replace the dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

The arguments for currency fixed on a basket of commodities – as opposed to currencies – was that it would stabilize the average prices of commodities, and with them the international medium of exchange and a store of value.

As China’s head central banker said in 2009, the goal would be to create a reserve currency “that is disconnected from individual nations and is able to remain stable in the long run, thus removing the inherent deficiencies caused by using credit-based national currencies”. Likewise, China suggested pegging SDRs to commodities.

Economics Professor Leanne Ussher of Queens College in New York concludes that a reserve currency made up of a basket of 30 or so commodities would:

Reduce the disorderly swings in individual commodity prices … reduce supply constraints, stabilize costs of production, promote global effective demand from the periphery and balance growth between periphery and core countries.

Monetary expert Bernard Liataer – formerly with Belgium’s Central Bank – writes:

The idea of a commodity-based currency may seem to some a step backwards to a more primitive form of exchange. But in fact, from a practical point of view, commodity-secured money (for example, gold- and silver-based money) is the only type of money that can be said to have passed the test of history in market economics. The kind of unsecured currency (bank notes and treasury notes) presently used by practically all countries has been acceptable only for about half a century, and the judgment of history regarding its soundness still remains to be written.

With a commodity-based currency, a central bank could issue a New Currency backed by a basket of from three to a dozen different commodities for which there are existing international commodity markets. For instance, 100 New Currency could be worth 0.05 ounces of gold, plus 3 ounces of silver, plus 15 pounds of copper, plus 1 barrel of oil, plus 5 pounds of wool.

This New Currency would be convertible because each of its component commodities is immediately convertible. It also offers several kinds of flexibility. The central bank would agree to deliver commodities from this basket whose value in foreign currency equals the value of that particular basket. The bank would be free to substitute certain commodities of the basket for others as long as they were also part of the basket. The bank could keep and trade its commodity inventories wherever the international market was most convenient for its own purposes–Zurich for gold, London for copper, New York for silver, and so on. Because of arbitrage between all these places, it doesn’t really matter where the trades would be executed, as the final hard currency proceeds would be practically equivalent. Finally, since the commodities also have futures markets, it would be perfectly possible for the bank to settle any forward amounts in New Currency, while offsetting the risks in the futures market if it so desired.

This flexibility results in a currency with very desirable characteristics. First of all, the reserves that the country could rely on–actual reserves plus production capacity–are much larger than its current stock of hard currencies and gold. The New Currency would be automatically convertible without the need for new international agreements. Since the necessary international commodity exchanges already exist, the system could be started unilaterally, without any negotiations. Because of the diversification offered by the basket of several commodities, the currency would be much more stable than any of its components–more stable, really, than any other convertible currency in today’s market.

The 2 choices for reserve currency discussed above are using a (1) basket of currencies or (2) basket of commodities.

A third choice – which may be the best – is to use a mixture.

For example, we could have 50% currencies and 50% commodities.

That would give us some of the desirable characteristics (like stability) of a commodity basket, but not immediately move away from the fiat money systems which are now status quo for the current system.

Any of these 3 choices would give us far more stability and prosperity than we have today … without the chaos and misery – especially for Americans and perhaps Chinese – that switching to a Yuan-only reserve currency would bring.

Notes: You might assume that public banking advocates would be for a currency-only basket. But Bernard Lietaer was one of leading public banking advocate Ellen Brown’s main teachers, and he is pushing for a basket made up solely of commodities. (But public banking advocates might argue for adding currencies to the basket currencies to allow for some elasticity in the money supply.)

Gold standard advocates would obviously prefer commodities to currencies. A basket of commodities might not have the simplicity of a gold standard, but it would accomplish a lot of the same goals.

As an American who wants stability and prosperity for my country, I think a basket would be the best option for a healthy future for the U.S. And as someone who wants good things for the rest of the world, I believe that a basket would help to share political influence more widely.

BONUS:

![]()

via Zero Hedge http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/zerohedge/feed/~3/dplJ6c0oYr0/story01.htm George Washington

Not only would SocGen be shocked if the Fed made any significant policy shift this week, they appear to be finding “belief” in a growth renaissance hard to sustain in light of the dismal reality that keeps getting in the way of ‘faith’. Undertaking any policy shifts at this meeting would be akin to driving at night with no headlights, they note, taking the opportunity to slash Q3 and Q4 GDP expectations – pushing off hope for any Taper announcement until late Q1 at its earliest. Of course, they remain “fundamentally bullish” on US growth (or every assumption about the world would implode) but the mid-year inflection point they hoped for appears to be further into the future than they hoped.

Via SocGen,

We expect no material changes in the FOMC statement this week, with odds of the Fed either increasing or decreasing the pace of purchases very close to zero. The economy is currently going through a period of uncertainty following the government shutdown, and has yet to digest fully the impact of higher rates. Therefore, we expect the Fed to take this opportunity to take stock of recent events, but opt to wait for more clarity before making any policy adjustments. We are also taking this opportunity to update our own economic forecasts. By our estimates, Q3 GDP is currently tracking at 2.3%, marginally lower than our published forecast of 3.0%. We are also downgrading our Q4 projection from 3.6% to 3.0% to account for the negative effects of the government shutdown. This would put the full- year growth rate at 2.2% on Q4/Q4 basis. We continue to look for a meaningful acceleration next year to 3.2%. We believe that these forecasts are consistent with a tapering announcement in late Q1.

Undertaking any policy shifts at this meeting would be akin to driving at night with no headlights. Since the September FOMC meeting, visibility on the outlook has not improved at all and, if anything, has gotten worse. The Fed’s concerns about fiscal policy have materialized, though the impact on growth remains uncertain. And, although financial conditions are easing again (see chart below), the net effect is still one of reduced visibility.

In this context, it would be far more prudent to wait for more clarity on the economic outlook. This is precisely what we expect the FOMC to do, not just this week, but also at the December meeting. In the meantime, the Fed will likely use the next two meetings as an opportunity to take stock of recent events and evaluate their impact on the economy.

Hitting a reset button on our economic forecasts

We also take the opportunity to update our GDP projections to account for recent events. Data available to date suggests that the economy clocked in a 2.3% annualized growth rate in Q3, i.e. marginally lower than our published forecast of 3%. The chart below shows a breakdown of contributions to growth by sector. While nearly every sector of the economy has shown some deceleration vs. Q2, consumer demand is the major reason for our revision, with real consumption now assumed to have grown at just 1.5% (today’s retail sales will be the next key data input into this estimate). We are also revising down our Q4 forecast from 3.6% to 3.0% to account for the effects of the government shutdown and for the slightly weaker momentum coming out of Q3.

We remain fundamentally bullish on the US growth. Since the start of the year, we have been calling for an inflection point around mid-year as the last of the headwinds began to dissipate. While the government shutdown has prolonged the period of fiscal uncertainty, the reality remains that new austerity – above and beyond what was legislated at the start of this year – is quite unlikely. Policy uncertainty is also on a downtrend, notwithstanding recent spike. And, housing should continue to be supported by declining real mortgage rates.

So in summary, our bullish hope based forecasts missed by a mile, so we are taking a hatchet to them, time-shifting them, and hope that we will be right again at some point in the future…

![]()

via Zero Hedge http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/zerohedge/feed/~3/lZNEjYsEUx8/story01.htm Tyler Durden

Not only would SocGen be shocked if the Fed made any significant policy shift this week, they appear to be finding “belief” in a growth renaissance hard to sustain in light of the dismal reality that keeps getting in the way of ‘faith’. Undertaking any policy shifts at this meeting would be akin to driving at night with no headlights, they note, taking the opportunity to slash Q3 and Q4 GDP expectations – pushing off hope for any Taper announcement until late Q1 at its earliest. Of course, they remain “fundamentally bullish” on US growth (or every assumption about the world would implode) but the mid-year inflection point they hoped for appears to be further into the future than they hoped.

Via SocGen,

We expect no material changes in the FOMC statement this week, with odds of the Fed either increasing or decreasing the pace of purchases very close to zero. The economy is currently going through a period of uncertainty following the government shutdown, and has yet to digest fully the impact of higher rates. Therefore, we expect the Fed to take this opportunity to take stock of recent events, but opt to wait for more clarity before making any policy adjustments. We are also taking this opportunity to update our own economic forecasts. By our estimates, Q3 GDP is currently tracking at 2.3%, marginally lower than our published forecast of 3.0%. We are also downgrading our Q4 projection from 3.6% to 3.0% to account for the negative effects of the government shutdown. This would put the full- year growth rate at 2.2% on Q4/Q4 basis. We continue to look for a meaningful acceleration next year to 3.2%. We believe that these forecasts are consistent with a tapering announcement in late Q1.

Undertaking any policy shifts at this meeting would be akin to driving at night with no headlights. Since the September FOMC meeting, visibility on the outlook has not improved at all and, if anything, has gotten worse. The Fed’s concerns about fiscal policy have materialized, though the impact on growth remains uncertain. And, although financial conditions are easing again (see chart below), the net effect is still one of reduced visibility.

In this context, it would be far more prudent to wait for more clarity on the economic outlook. This is precisely what we expect the FOMC to do, not just this week, but also at the December meeting. In the meantime, the Fed will likely use the next two meetings as an opportunity to take stock of recent events and evaluate their impact on the economy.

Hitting a reset button on our economic forecasts

We also take the opportunity to update our GDP projections to account for recent events. Data available to date suggests that the economy clocked in a 2.3% annualized growth rate in Q3, i.e. marginally lower than our published forecast of 3%. The chart below shows a breakdown of contributions to growth by sector. While nearly every sector of the economy has shown some deceleration vs. Q2, consumer demand is the major reason for our revision, with real consumption now assumed to have grown at just 1.5% (today’s retail sales will be the next key data input into this estimate). We are also revising down our Q4 forecast from 3.6% to 3.0% to account for the effects of the government shutdown and for the slightly weaker momentum coming out of Q3.

We remain fundamentally bullish on the US growth. Since the start of the year, we have been calling for an inflection point around mid-year as the last of the headwinds began to dissipate. While the government shutdown has prolonged the period of fiscal uncertainty, the reality remains that new austerity – above and beyond what was legislated at the start of this year – is quite unlikely. Policy uncertainty is also on a downtrend, notwithstanding recent spike. And, housing should continue to be supported by declining real mortgage rates.

So in summary, our bullish hope based forecasts missed by a mile, so we are taking a hatchet to them, time-shifting them, and hope that we will be right again at some point in the future…

![]()

via Zero Hedge http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/zerohedge/feed/~3/lZNEjYsEUx8/story01.htm Tyler Durden

Submitted by Alasdair Macleod via GoldMoney.com,

A number of people have asked me to expand on how the rapid expansion of money supply leads to an effect the opposite of that intended: a fall in economic activity. This effect starts early in the recovery phase of the credit cycle, and is particularly marked today because of the aggressive rate of monetary inflation. This article takes the reader through the events that lead to this inevitable outcome.

There are two indisputable economic facts to bear in mind. The first is that GDP is simply a money-total of economic transactions, and a central bank fosters an increase in GDP by making available more money and therefore bank credit to inflate this number. This is not the same as genuine economic progress, which is what consumers desire and entrepreneurs provide in an unfettered market with reliable money. The second fact is that newly issued money is not absorbed into an economy evenly: it has to be handed to someone first, like a bank or government department, who in turn passes it on to someone else through their dealings and so on, step by step until it is finally dispersed.

As new money enters the economy, it naturally drives up the prices of goods bought with it. This means that someone seeking to buy a similar product without the benefit of new money finds it is more expensive, or put more correctly the purchasing power of his wages and savings has fallen relative to that product. Therefore, the new money benefits those that first obtain it at the expense of everyone else. Obviously, if large amounts of new money are being mobilised by a central bank, as is the case today, the transfer of wealth from those who receive the money later to those who get it early will be correspondingly greater.

Now let’s look at today’s monetary environment in the United States. The wealth-transfer effect is not being adequately recorded, because official inflation statistics do not capture the real increase in consumer prices. The difference between official figures and a truer estimate of US inflation is illustrated by John Williams of Shadowstats.com, who estimates it to be 7% higher than the official rate at roughly 9%, using the government’s computation methodology prior to 1980. Simplistically and assuming no wage inflation, this approximates to the current rate of wealth transfer from the majority of people to those that first receive the new money from the central bank.

The Fed is busy financing most of the Government’s borrowing. The newly-issued money in Government’s hands is distributed widely, and maintains prices of most basic goods and services at a higher level than they would otherwise be. However, in providing this funding, the Fed creates excess reserves on its own balance sheet, and it is this money we are considering.

The reserves on the Fed’s balance sheet are actually deposits, the assets of commercial banks and other domestic and foreign depository institutions that use the Fed as a bank, in the same way the rest of us have bank deposits at a commercial bank. So even though these deposits are on the Fed’s balance sheet, they are the property of individual banks.

These banks are free to draw down on their deposits at the Fed, just as you and I can draw down our deposits. However, because US banks have been risk-averse and under regulatory pressure to improve their own financial position, they have tended to leave money on deposit at the Fed, rather than employ it for financial activities. There are signs this is changing.

Rather than earn a quarter of one per cent, some of this deposit money has been employed in financial speculation in derivative markets, or found its way into the stock market, gone into residential property, and some is now going into consumer loans for credit-worthy borrowers.

In addition to the government’s deficit spending, these channels represent ways in which money is entering the economy. Furthermore, anyone working in the main finance centres is being paid well, so prices in New York and London are driven higher than in other cities and in the country as a whole. They spend their bonuses on flashy cars and country houses, benefiting salesmen and property values in fashionable locations. And with stock prices close to their all-time highs, investors with portfolios everywhere feel financially better off, so they can increase their spending as well.

All the extra spending boosts GDP, and to some extent it has a snowball effect. Banks loosen their purse strings a little more, and spending increases further. But the number of people benefiting is only a small minority of the population. The rest, low-paid workers on fixed incomes, pensioners, people living on modest savings in cash at the bank, and part time employed as well as the unemployed find their cost of living has gone up. They all think prices have risen, and don’t understand that their earnings, pensions and savings have been reduced by monetary inflation: they are the ultimate victims of wealth transfer.

While luxury goods are in strong demand in London and New York, general merchants in the country find trading conditions tough. Higher prices are forcing most people to spend less, or to seek cheaper alternatives. Manufacturers of everyday goods have to find ways to reduce costs, including firing staff. After all if you transfer wealth from ordinary folk they will simply spend less and businesses will suffer.

So we have a paradox: growth in GDP remains positive; indeed artificially strong because of the under-recording of inflation, while in truth the economy is in a slump. The increase in GDP, which reflects the money being spent by the fortunate few before it is absorbed into general circulation, conceals a worse economic situation than before. The effect of an expansion of new money into an economy does not make the majority of people better off; instead it makes them worse off because of the wealth transfer effect. No wonder unemployment remains stubbornly high.

It is the commonest fallacy in economics today that monetary inflation stimulates activity. Instead, it benefits the few at the expense of the majority. The experience of all currency inflations is just that, and the worse the inflation the more the majority of the population is impoverished.

The problem for central banks is that the alternative to maintaining an increasing pace of monetary growth is to risk triggering a widespread debt crisis involving both over-indebted governments and also over-extended businesses and home-owners. This was why the concept of tapering, or putting a brake on the rate of money creation, destabilised worldwide markets and was rapidly abandoned. With undercapitalised banks already squeezed between bad debts and depositor liabilities, there is the potential for a cascade of financial failures. And while many central bankers could profit by reading and understanding this article, the truth is they are not appointed to face up to the reality that monetary inflation is economically destructive, and that escalating currency expansion taken to its logical conclusion means the currency itself will eventually become worthless.

![]()

via Zero Hedge http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/zerohedge/feed/~3/8ZxAPyhdcnQ/story01.htm Tyler Durden

By: Chris Tell at http://capitalistexploits.at/

I’ve never been trapped in a fire before and trust me, I have had plenty of opportunity. Yes, I was THAT kid, the one who played with fire. The trick was, and still is to steer clear of the flames, to anticipate what and where. Fire is however notorious for doing what it wants and once its out of control even the best firefighters don’t stand a chance.

Each day that passes we come closer to the arrival of a monetary fire that threatens to dwarf anything in our collective living memories. Watching the Australian bush fires in New South Whales recently made me think of our monetary system. Funny that.

The Australian bush has been burning long before the Brits began exporting their best and brightest to the “lucky country.” Right now the fires are raging. It was inevitable. Like the business cycle nature too abhors excess and steps in to correct it, clear the dead wood and prepare for rebirth.

What is often forgotten is that nature has evolved to rely on bush-fires as a means of reproduction and new “birth.” Fires are an integral part of the ecology of the planet’s surface. Humans can try and prevent these inevitable fires by “controlled burnings”, clearing out much of the dead underbrush, but it’s not foolproof.

The fires now raging in New South Whales are in part due to an extensive build up of dry brush which is likely overdue a good burning. The longer the dry bush remains unburned, and the more that accumulates the greater the risk of an inevitable fire. The result will be much greater than that which would have preceded it should a fire have taken place sooner. This is a basic, easy to understand law of nature.

Financial markets are NO different. The dry brush of excessive credit, monetary stimulus, rampant fraud, and government interference, which has caused the largest sovereign bond bubble the world has ever seen, has not been cleared or burned to allow for regeneration. In contrast we’ve actually been ADDING to it, doing the exact opposite of the “controlled burn.”

The market, like nature, has attempted to correct these excesses many times, only to be met with central bankers fire hoses spraying liquidity at ever increasing volumes and velocity. As the outbreaks of financial fires increase so too do the tools and technologies used by the central bankers. This postponement of the inevitable leads to massive mis-allocation of capital.

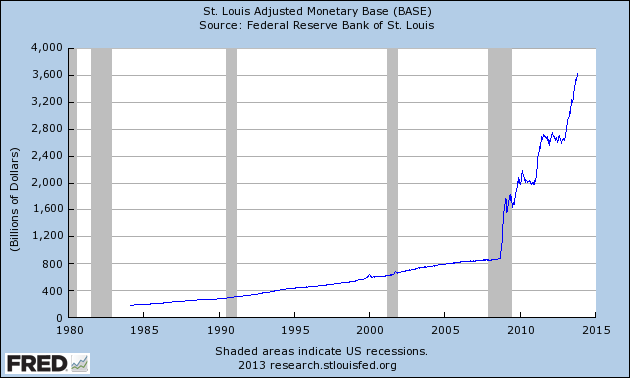

That’s a lot of dead wood buildup there

The above graph shows all the dead wood build-up. Quite a bonfire awaits us.

It is possible that the fires will continue to be contained, central bankers promise that this is indeed the case. We DO know however that it is not possible to contain it forever. This time is not different…or is it?

Let’s compare what’s different this time around in Australia and the world’s monetary system?

What’s happening in New South Wales right now provides us with an instruction manual for how to proceed forward in a world of monetary madness. We need to BURN THE UNDERBRUSH. Simply hoping that the fires will fail to erupt simply defies history and mathematics. “Hope and Change” be damned.

The likely outcome is that we’re heading deep into asset confiscation mode. Government meddling will fail, it always has and it always will. The playbook from throughout history tells us that governments will steal anything and everything from the most productive before they default.

This happens either overtly (taxation, fines, penalties, asset seizure) or covertly via destruction of currencies (quantitative easing). Everything not nailed down is up for grabs. Don’t say you weren’t warned! If you need an example look at what’s happening in France. Hollande is insane, but he’s not unique.

As such, aside from structuring myself in order to protect what I have, which I hope I’ve done, ensuring that what I invest in going forward is structured properly is just as important. It makes no sense to invest intelligently only to have some thug steal the proceeds because I failed to set myself up to deal with the inevitability just mentioned.

So, how are Mark and I choosing to allocate our capital:

The above is neither a recommendation nor an endorsement of any particular asset class or strategy. Obviously everyone’s situation is different, and we don’t know yours. Some could probably do just fine with a couple hunting rifles, some ammo and a nice piece of land to grow food and run a few livestock. Albeit that’s not going to work for urban dwellers.

The bottom line is that we are just encouraging you to consider how to prepare for a monetary firestorm. Do it your own way, use common sense, but just don’t be the dupe who ignores the obvious.

– Chris

“So just as I want pilots on the planes that I fly, when it comes to monetary policy, I want to think that there is someone with sound judgement at the controls.” – Martin Feldstein

![]()

via Zero Hedge http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/zerohedge/feed/~3/nm9tXpH-L0I/story01.htm Capitalist Exploits

Today’s AM fix was USD 1,346.75, EUR 978.81 and GBP 837.06 per ounce.

Yesterday’s AM fix was USD 1,351.00, EUR 978.28and GBP 833.69per ounce.

Gold climbed $1.50 or 0.11% yesterday, closing at $1,353.00/oz. Silver slipped $0.05 or 0.22% closing at $22.47. Platinum rose $9.20 or 0.7% to $1,382.00/oz, while palladium climbed $6.50 or 0.9% to $707/oz.

Gold for immediate delivery gained as much as 0.6% to $1,360.76/oz, prior to a sharp bout of concentrated selling just before European markets opened at 0800 GMT, that saw gold fall to just above $1,340/oz .

Gold had been near the highest level in five weeks after U.S. economic data showed how weak the U.S. economy remains leading to concerns that the Fed will continue with ultra loose monetary policies.

Gold in US Dollars, 10 Days – (Bloomberg)

Gold is currently 1.3% higher in October. Gold fell into the middle of the month (see chart below) and then as U.S. lawmakers wrangled over the nation’s budget and debt ceiling, triggering a 16-day partial government shutdown, gold began to recover and is now nearly $100 above the low seen mid October at $1,252/oz.

U.S. factory output trailed forecasts in September, while pending sales of previously owned homes fell the most in three years, separate reports showed yesterday.

Asian demand remains robust and holdings in the SPDR Gold Trust, the biggest gold exchange traded product, held steady at 872.02 metric tons yesterday.

Gold in US Dollars, 1 Month – (Bloomberg)

In the Financial Times, veteran financial journalist and gold watcher, John Dizardnoted the increasing strain in the physical gold market and detailed how that should lead to much higher

gold prices.

“Something is unsettling the animals in the forest of the gold market. Usually there is a chorus of chirrups and squeaks that are significant, momentarily, for one species or another, such as a few cents of arbitrage between Zurich and London, or a dollar-an-ounce rise in India caused by a dealer’s near insolvency. Then the noise settles down to the murmur of wind through the trees

However, the continuing high level of premiums for physical gold over the kinds you can trade on a screen suggests that the next move in the major gold indices or the various exchange traded funds could be discontinuous and dramatic. It would be much better for the financial world if gold were just bumping along, with only enough volatility and liquidity to keep a few dealers’ lights on. That would mean electronic or paper assets have retained their essential credibility with the public …”

“This could turn into a very violent wake-up call for [screen-traded gold]. People talk about ‘fiat currencies’, but we also have ‘fiat gold.’ Volatility is too cheap right now.”

Taken together, this collection of persistent microeconomic signals in gold could flag macro trouble to come. These noises worried me in August. They worry me more now.

Dizard’s article, ‘Strange gofo cry heralds trouble for gold’ in the Financial Times can be read here.

He has previously warned that ETF gold holdings and central bank gold reserves may be being lent to bullion banks, who then re lend that gold into the market.

Owners of gold exchange traded funds (ETFs) would be surprised and worried to discover that certain banks might be lending out gold that they have bought and believe that they own.

The leading gold ETF, GLD has been criticised by many analysts for its extremely complex structure and prospectus. There have also been warnings about the possible conflict of interest and overall lack of transparency.

If as has been suggested, banks are lending gold into the market that has come from exchange traded funds then this would validate the many concerns raised about the gold ETF market.

Questions would again be asked as to whether many of the ETFs are fully backed by the gold that they claim to own in trust on behalf of clients.

Gold Prices / Fixes /Rates /Volumes – (Bloomberg)

Already more prudent hedge fund, investment and pension fund managers have liquidated their ETF positions in favour of allocated physical bullion.

We would expect that trend to accelerate as prudent investors rightly seek to avoid the high level of counterparty and systemic risk associated with exchange traded gold and other forms of unallocated gold and paper gold.

![]()

via Zero Hedge http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/zerohedge/feed/~3/LdEbZ7mHGG0/story01.htm GoldCore