Via Angry Bear blog,

Introductory note: this is a very long epistle. But I think my point needs to be made fully and at length. Before you go further, in fairness here is the TL:DR version:

-

Advocates of free trade and globalization were taken aback a week ago by the assumption by China’s President Xi Jinping of rule for life.

-

This was because it runs completely contrary to their theory that free trade leads to economic liberalization, which in turn leads to political liberalization.

-

This theory has been repeatedly and thoroughly repudiated throughout history, most catastrophically be World War I.

-

That’s because autocrats will use the gains of economic trade for their own ends, typically the pursuit of further political and military power.

-

Historically middle classes do not revolt against autocracy when they are prospering, but rather only after a period of rising expectations has been dashed by an economic downturn in which the autocratic elite unfairly forces all of the burden onto them.

-

But since these historical facts are nowhere to be found in the economic models, they are ignored as if they do not exist. We can only hope they do not once again lead to catastrophe.

First, let me pose a thought experiment. Country A and Country B propose to enter into Agreement X. We have no idea at all what Agreement X is, but we know that the result will be that both Country A and Country B will each be richer by $1 Trillion each and every year thereafter.

Country A, being an egalitarian paradise, is going to share out the proceeds equally among its population of 250 million, with each person getting $4,000 per year.

The dictator of Country B is going to do the same with 1/2 of its $1 Trillion gain, making his population very happy, but — because this is his personal aim — he is going to spend the other $500 Billion each and every year in building up its military so that it can challenge and eventually vanquish Country A, and then keep all of the gains of Agreement X to itself.

Should Country A enter into Agreement X?

* * *

A week ago The Economist opined that “The West’s Bet on China has Failed,” stating that:

Last week China stepped from autonomy into dictatorship. That was when Xi Jinping … let it be known that he will change China’s constitution so that he can rule as president for as long as he chooses …. This is not just a big change for China but also strong evidence that the West’s 25 year long bet on China has failed.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the West welcomed [China] into the global economic order. Western leaders believed that by giving China a stake in institutions such as the World Trade Organization would bind it into the rules based system … They hoped that economic integration would encourage China to evolve into a market economy and that, as its people grew wealthier, its people would come to yearn for democratic reforms ….

CNN’s Fareed Zakaria recoiled in horror, writing in the Washington Post that

[W]hat’s happening in China … is huge and consequential. China is making the most significant change to its political system in 35 years.

For decades, China seemed to be getting more institutionalized…. But that trend has now been turned on its head. If term limits are abolished, which is now almost certain, Xi Jinping could stay China’s president, general secretary of the Communist Party and chairman of the Central Military Commission for the rest of his life. And he is just 64.

… The real danger is that China is eliminating perhaps the central restraint in a system that provides staggering amounts of power to the country’s leaders. What will that do, over time, to the ambitions and appetites of leaders? “Power tends to corrupt,” Lord Acton famously wrote in 1887, “and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Perhaps China will avoid this tendency, but it has been widespread throughout history.

If Zakaria felt blindsided, he should not have been. Because ten years ago, after he published “The Post-American World,” arguing that because the US had successfully spread the ideals of liberal democracy across the world, other countries were competing for economic, industrial, and cultural – but not military – power, I confronted him at the former TPM Cafe.

For the truth is, the West’s bet on China, so ruefully mourned by The Economist and Zakaria, was always likely to fail. That free trade leads to economic and political liberalism and to peace – championed by neoliberal economists and their political retinue – has been a fantasy for over 100 years, and for 100 years it has been a lie. They would have known if their theories and equations could account for the likes of Kaiser Wilhelm II. But since their equations and theories are blind to the pursuit of power, they dismiss it — at horrible cost to the world.

In an interview with David Frum, Minxin Pei, who a decade ago dissented, predicting that China would not transition towards true economic and political freedom, said it well:

[M]any people were too dazzled by the superficial changes, especially economic changes, to realize that the Communist Party’s objective is to stay in power, not to reform itself out of existence. Economic reform or, to be more exact, adopting some capitalist practices and embracing market in some areas, is only a means to a political end…

W]hen China was forced to keep the door [to liberalization] more open, it was in a weaker position relative to the forces outside—the West in general and the U.S. in particular. But when the conservative forces inside China gain strength while the West appears to be in decline, those forces are far more likely and able to close the door again, as is happening right now. So, while the logic of irresistible liberalization appears to be reasonable on the surface, it overlooks the underlying reality of power.

I set set forth the fuller historical context a decade ago in my response to Zakaria,which I am taking the liberty of reposting in full immediately below.

* * *

Over at TPM Cafe, this week Fareed Zakaria’s new book, “The Post American World” is being discussed. In it, Zakaria repeats the theory of globalization’s most toxic and unproven claim: that countries which participate in trade together do not make war upon one another. So if you want to prevent war, just participate in deep and interwoven trade with the other country and everything will be hunky-dory.

It’s a lie.

Zakaria claims that We’re Living in Scarily Peaceful Times”:

The new and most dangerous twist to all this is that our great looming danger is Russia, China, and the rising oil dictatorships…. This is a worldview bereft of any historical perspective. Compared with any previous era, there is more economic integration and even comity among the world’s major powers. The imbalance between the West and the rest is large, not complete but large and in most areas increasing. The newly emerging states want to grow within the existing world order, which John Ikenberry has nicely described as “easy to join and hard to overturn.” The world is going our way, slowly and fitfully, with some detours. No great power has an alternative model of modern life that has any real attraction?

This is essentially the same argument that Thomas Friedman made in The Lexus and the Olive Tree’ and reiterated even a short time ago in this liveblog:

You know in Lexus I wrote that no two countries would fight a war so long as they both had McDonald’s. And I was really trying to give an example of how when a country gets a middle class big enough to sustain a McDonald’s network, they generally want to focus on economic development. That is a sort of tipping point, rather than fighting wars.

This argument, repeated over and over on both necoconservative and neoliberal sites, and all over the corporate media, that free trade leads to middle classes leads to democracy leads to kumbayah, is pretty simple, and it is dangerously wrong. Or as Zakaria reviewer David Rieff summarizes:

he reads too much into into two indisputable facts of the current moment — that there are fewer major wars taking place than in living memory and that there is a greater level of global economic integration than at any time in history.

The truth is, the free trade zealots also have spent too much of their careers seduced by neoclassical economics’ favorite mythical beast, Homo economicus, the Rational Man; and not enough time reading history.

For a start, contrary to the free trade zealots, this is not the first period in world history in which there has been relatively “free” trade, nor is it the first time in which there has been “globalization.” For example, as is pointed out in an article entitled European Social Security and Global Politics By Danny Pieters, European Institute for Social Security Conference

Globalisation is not a new phenomena. During the second part of the nineteenth century there was a strong move toward the liberalisation of international transactioins, and international trade expanded rapidly until the beginning of World War I

And just which country in Europe was undergoing the most rapid growth and industrialization during the perioed from 1870-1914? As this essay states, Germany

embarked upon an extensive education program; it specialised in technical ares and so there was a greater push in that direction. It produced more and better scientists, and so Germany began her industrial advance. Also, the French threat, even if it was superficial, spurred the Germans in authority into action, and made them make Germany stronger and superior.

German expansion was also helped by the expansion of the railway network, so that goods and mail could get from one place to another, and to more places, faster and more efficiently.

Needless to say,much like the mercantilist expanding autocracies now fawned over by so many of the free trade zealots, during this time Germany was a monarchy, ruled by the Kaiser.

Even worse, this isn’t just the first time that economies have experience “globalization”, it also isn’t the first time that this exact same argument has been made. In his 1910 best-seller, “The Great Illusion” Norman Angell wrote that:

the universal assumption that a nation, in order to find outlets for expanding population and increasing industry, or simply to ensure the best conditions possible for its people, is necessarily pushed to territorial expansion and the exercise of political force against others…. It is assumed that a nation’s relative prosperity is broadly determined by its political power; that nations being competing units, advantage in the last resort goes to the possessor of preponderant military force, the weaker goes to the wall, as in the other forms of the struggle for life.

The author challenges this whole doctrine. He attempts to show that it belongs to a stage of development out of which we have passed that the commerce and industry of a people no longer depend upon the expansion of its political frontiers; that a nation’s political and economic frontiers do not now necessarily coincide; that military power is socially and economically futile, and can have no relation to the prosperity of the people exercising it; that it is impossible for one nation to seize by force the wealth or trade of another — to enrich itself by subjugating, or imposing its will by force on another; that in short, war, even when victorious, can no longer achieve those aims for which people strive….

There is quite simply no difference at all between the theses of Angell a century ago, and Friedman and Zakaria now.

And what happened only 4 years after “The Great Illusion” was published? Well, another book that Zakaria and Friedman ought to read is Vera Brittain’s autobiography, “Testament of Youth”. Vera Brittain was a comfortable affuent middle class girl who was accepted to Oxford University shortly before World War I broke out. By the time it was over, her brother, Edward; her fiance Roland Leighton; and every other young man she had been close to, had been killed. Brittain’s book is a searing documentary about the utter destruction of an entire generation of British young men caused by the war.

Just how many people were killed by World War I? One source puts just the number of military deaths at 10 million. Including the wounded, in some European countries over half of the entire generation of young men were casualties. Another sourcesays:

the percentage of a country’s population directly afflicted. During the course of World War One, eleven percent (11%) of France’s entire population were killed or wounded! Eight percent (8%) of Great Britain’s population were killed or wounded, and nine percent (9%) of Germany’s pre-war population were killed or wounded! The United States, which did not enter the land war in strength until 1918, suffered one-third of one percent (0.37%) of its population killed or wounded.

Simply put, World War I is a thorough and devastating refutation of the argument that free trade leads to peace and democracy. Quite the contrary, had Zakaria and Friedman bothered to actually study history, they might have found out that revolutions typically do not occur in eras of increasing plenty. Rather, they occur in times where rising expectations have been dashed:

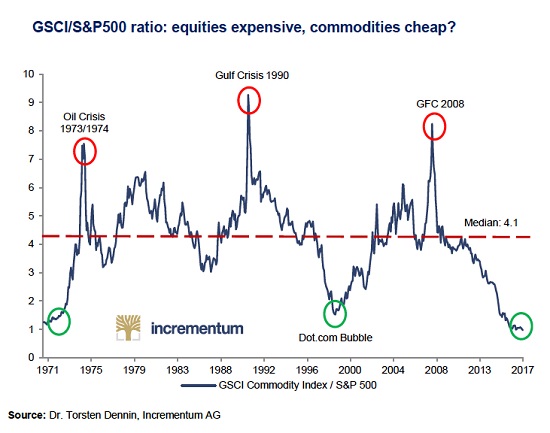

the “J-curve” theory says that when conditions improve for a relatively long period of time, — and this is followed by a short economic reversal — an intolerable gap occurs between the changes that the people expect (dashed line) and what they actually get (solid line). Davies predicts that this is when revolution will occur (arrow).

Support for this theory was found in a 1972 study of 84 nations. Researchers found a clear relationship between indications of political instability and economic frustration. “Frustrated countries” are those that had poor economic conditions — low economic growth, insufficient food, few telephones and physicians — while being acquainted with the higher living standards of industrialized, urbanized countries.

These studies show that frustration is more likely to develop from relative frustration — the gap between their expectations and the reality that does not live up to these expectations. People in poor countries isolated from the outside world do not realize how poor or frustrated they are. Their frustrations are accepted merely as part of living. In contrast, the people in poorer countries exposed to modern standards feel more “frustrated.” To top this off, deprived people who have experienced some recent progress are more frustrated than those who experienced poverty and oppression.

In short, just as Germans were hardly big agitators for democracy during the time the German state was expanding, and autocracy was resulting in greater prosperity, so we should not expect that any autocratic states today that are profiting mightily from economic growth are suddenly going to turn democratic. To the contrary, just like the Kaiser’s Germany, it is much easier to direct aggression elsewhere.

Democratic revolutions occur when previously rising expectations have been dashed, and the populace has no outlet for their anger and frustration. In democracies, governments can be changed (as in 1932); but in autocracies, the ruler’s cronies are protected from the privations, and with no alternative avenue of recourse, and seeing the manifest injustice of the benefits of the system, the populace revolts.

For example, Taiwan’s democratic reforms were sparked by the violence of the “Kaohsiung Incident” of 1979. Similarly, democracy finally came to South Korea in 1987 when workers finally rebelled against artificially low wages:

South Korea is hardly a model of a free economy. The hand of government planners in setting priorities and steering companies has been heavy. The low wages that helped fuel growth did not result from market forces. For 25 years, successive governments deliberately held down pay rates. They virtually barred strikes, jailed militant labor leaders, and decreed tough guidelines for wage increases. To block development of independent unions, companies created their own and installed leaders acceptable to the government. Says a Western diplomat in Seoul: ”Union leaders were practically appointed by the national security police.” With democratic winds sweeping South Korea this summer, workers were emboldened to push for higher pay, independent unions, and the right to strike,

[2018 update: Even the American Revolution had elements of this paradigm, as England reined in the colonist’s rising fortunes following the French and Indian War by taxing them for the costs, expanding the territory of Quebec to include all of what is now the American northern Midwest, and prohibiting expansion beyond the Appalachians.]

It is a disgrace that we see these same discredited theses, this same Great Illusion, embraced by corporate media pundits so often. That free trade inevitably leads to peace and democracy is a Big and Dangerous Lie, to which World War 1 is the most spectacular and unequivocal counter-evidence.

There is no guarantee, alas, that we are not now on that same catastrophic path.

* * *

In 2015, I reiterated this point more succinctly:

A more fundamental point is about human nature. In any economic downturn, the powerful elites are going to try to deflect all of the suffering on the powerless masses. In a representative democracy, eventually the majority will rebel at the ballot box and elect a party which promises to end their suffering. [Update: It might be a left-wing party, like Syriza in Greece or FDR’s New Deal democrats in the US, or it might be from the right-wing like AfD in Germany or Donald Trump. ]

In an authoritarian state, however, no such safety valve exists. That’s why revolutions don’t happen in an era of rising expectations. They happen when rising expectations are dashed. So long as China’s economy continues to expand stoutly, expect no meaningful turbulence. But someday China will have a recession, and then, dear reader, is when world history will get interesting.

So here we are a decade later, and the free-trade economists and their acolytes are gobsmacked by something that was not just predictable, but actually predicted, because there is no place in their theories for actual human behavior as revealed in history. We can only hope that when the inevitable happens, China will not lash out as Kaiser Wilhelm did a century ago.

via RSS https://ift.tt/2E9MWjT Tyler Durden

* * *

* * *