Chicago impounds thousands of people’s cars a year, including cars owned by people who have committed no crime, and forces them through an expensive, bureaucratic maze to get their car back. This process that violates residents’ constitutional rights, according to a new lawsuit filed against the city Monday evening.

The Institute for Justice filed a class-action lawsuit in Illinois state court alleging that Chicago’s impound program violates residents’ guarantee of due process, as well as protections against excessive fines and unreasonable seizures, under both the Illinois and U.S. constitutions.

“Owners find themselves in a labyrinthine impound system that is plagued by serious procedural flaws,” the suit says. “Even innocent owners get caught up in this system, facing hefty fines and fees when someone else used their car to commit a crime without the car owner’s knowledge.”

A Reason investigation published last year described how Chicago’s punitive impound program soaks people in fines and fees and deprives them indefinitely of their transportation, whether or not they actually committed an offense, in an effort to reduce its massive annual budget deficits. It also operates independently from the state’s courts, meaning that even in cases where a defendant beats a criminal charge and/or a civil asset forfeiture case, they can still be found liable for thousands of dollars in fines and storage fees, and have their cars held until they pay or relinquish them to the city, by Chicago.

That’s exactly what happened to Spencer Byrd, a 51-year-old resident of Harvey, Illinois whose impound case was featured by Reason and is now a named plaintiff in the Institute for Justice lawsuit.

Byrd, a part-time auto mechanic says he was giving a client a lift in his 1996 Cadillac DeVille one evening in June, 2016, when he was pulled over by Chicago police and searched. Byrd was clean, but his passenger, a man he says he’d never met before, had heroin in his pocket.

The police released Byrd without charging him with a crime, but his car was seized and dually claimed by both the Cook County State Attorney’s Office and the city of Chicago. He’s been fighting for nearly three years to get it back.

A state judge ordered Byrd’s car released after he filed a financial hardship motion, but the city refused to return it, claiming he owed money under the city’s municipal code.

Even after a state judge declared Byrd innocent in the civil forfeiture case against his Cadillac in Illinois state court, he was still found liable for violating Chicago’s municipal code in the city’s administrative hearings court, which has a low standard of evidence and almost no procedural protections for defendants.

In the meantime, Byrd’s livelihood has suffered. His primary trade is carpentry, but his tools have been locked in his car since it was impounded. The city has refused to let him retrieve them, or his car, until he pays his accumulated fines and fees, which according to the lawsuit now stand at more than $17,000.

“If you do wrong, fine, but I didn’t do nothing wrong,” Byrd tells Reason. “I should have had my car released to me with no fines or anything—thank you, sorry for the inconvenience, and I’m on my merry way—instead of trying to get some type of revenue from me. I was proven innocent, and they still didn’t want to act right.”

Byrd is far from alone. A WBEZ analysis of Chicago’s massive impound program found that in 2017 alone, the city impounded more than 22,000 cars for violations of its municipal code, which includes dozens of impoundable offenses ranging from drug possession to drag racing to having illegal fireworks.

The fines for those violations are steep, ranging from $500 to $3,000, and that doesn’t include towing and storage fees, which accumulate at $20 a day for the first five days, and $35 a a day after that. Given that these cases can take weeks, if not months, to wind through the system, the fees can often exceed the fines themselves.

A Reason analysis of data from the Chicago Administrative Hearings Department showed Chicago fined motorists $17 million over a 12-month period between 2017 and 2018. About $10 million of those fines were for driving on a suspended license, and more than $3 million were for drug offenses like the one that resulted in the impoundment of Byrd’s car.

Chicago can hold seized cars indefinitely. There is also no statute of limitations on impound fines and fees in Chicago. The debt can follow someone for life.

Chicago’s impound racket is both easy to be ensnared in and hard to escape. There are only three narrow defenses for those whose cars are impounded for municipal violations in Chicago, and being an innocent owner isn’t one of them.

“You’re talking about a lot of money for something that you may not have been responsible for,” says Institute for Justice attorney Diana Simpson. “The lack of an innocent owner protection really violates two different kinds of constitutional protections: both the excessive fines and fees protection, as well as due process.”

The case of two of the other named plaintiffs in the Institute for Justice lawsuit, Jerome Davis and Veronica Walker-Davis, exemplify what critics say is the procedural nightmare people face when their cars are impounded in Chicago.

In May of last year, the couple dropped their 2006 Lexus off at a Chicago body shop following an accident. When the repairs dragged on for longer than expected, the shop first said it was waiting for parts, but eventually the couple learned the truth: An employee of the shop had driven their car on a suspended license and was pulled over. Their Lexus was now sitting at one of Chicago’s six impound lots.

The city had never informed the couple that their car had been impounded, according to the lawsuit, and Veronica Walker-Davis had to travel in person to the city’s administrative hearings building to request a hearing to fight the impoundment.

“I’m thinking that I’m just going to go and give a statement, show proof that my car wasn’t in my possession, and everything will be okay, but in fact it turned into a nightmare,” she says. “I felt like I was pretty much in The Twilight Zone.”

The Twilight Zone is Room 110 in Chicago’s administrative hearings building, a small courtroom where the city churns through its impound cases at a rate of roughly one every 10-15 minutes, five days a week.

Because the hearings are civil matters, not criminal, there is no right to a lawyer, and Walker-Davis found herself standing across from a lawyer for the city of Chicago. She tried to explain to the administrative hearing judge what had happened, but it made no difference. She was found liable for violating the city code and would have to pay nearly $2,500 to get their car out of impound.

“I felt like crap,” she says. “I felt like a criminal.”

In late March of this year, The couple managed to find a pro bono lawyer and negotiate their fine down to $1,170, but when they arrived with cash in hand, they were told the registration on their car had lapsed in the more than six months it had been sitting in an impound lot, and the city would not release it without a current registration.

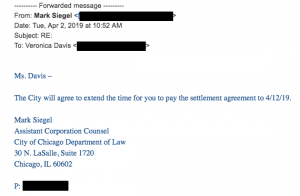

Walker-Davis rushed the next day to get their registration renewed, which cost another $101, and got the city to agree to extend the deadline for the couple to pay their impound fines. In an email provided to Reason, a lawyer for Chicago’s law department wrote to the couple: “The City will agree to extend the time for you to pay the settlement agreement to 4/12/19.”

But when the couple showed up to retrieve their car on April 10, it was gone. The city had already sold it off. According to WBEZ, Chicago sells many of the cars it impounds for paltry amounts under $200, and almost all of them are sold to a single towing contractor.

The Institute for Justice is hoping that a recent Supreme Court case will bolster their claim that Chicago’s rapacious impound program fines people so much and affords them so few avenues of escape that it violates the Constitution.

The Supreme Court ruled earlier this year in Timbs v. Indiana—the case of an Indiana man whose $42,000 Land Rover was seized for a drug felony—that states are bound by the Eighth Amendment’s protections against excessive fines and fees. Although the Court did not define exactly what constitutes “excessive,” it opened the door for civil liberties groups to press the issue.

In 2017, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals struck down Los Angeles’ automatic 30-day impound law, ruling that it amounted to an unconstitutional seizure under the Fourth Amendment. While state and federal courts have repeatedly upheld Chicago’s impound program in the past, the Institute for Justice hopes that it can build on the recent Supreme Court decision, as well as other cases that have addressed the government’s use of fines and fees to generate revenue.

“We think we’ve got a really great chance, and we think the courts will agree with us that the system is just too much,” Simpson says. “It’s bringing in an entirely huge amount of money for the city of Chicago—there’s about 22,000 cars that go in through this system each year—and that’s not the role of the government.”

from Latest – Reason.com http://bit.ly/2VylxEJ

via IFTTT