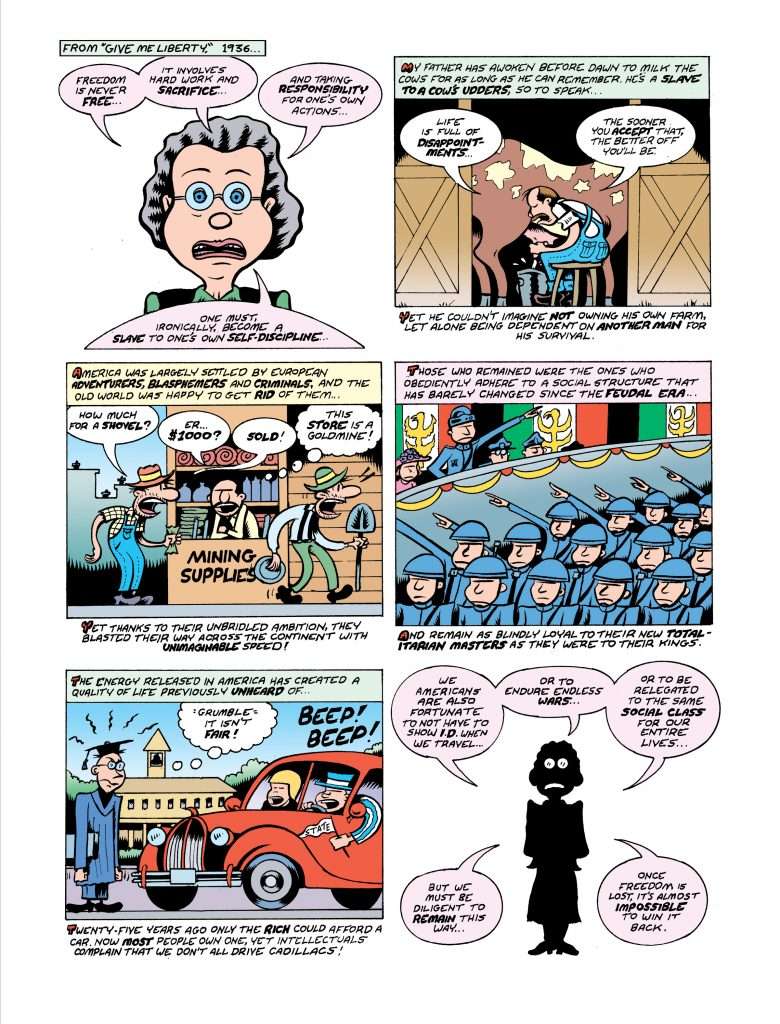

Rose Wilder Lane was born on December 5, 1886, in the territory of South Dakota. Her early years were a hardscrabble settler’s life similar to that of her mother, Laura Ingalls Wilder, whose Little House novels defined the American frontier for many generations of young readers.

After an early career writing for newspapers and penning popular biographies of figures such as Jack London, Charlie Chaplin, Herbert Hoover, and Henry Ford, Lane worked with the Red Cross in Europe in the 1920s. She adventured through Albania and parts of the Middle East, usually with close female companions, then moved to the Ozarks in Missouri to care for her parents.

Throughout the 1930s, Lane assisted her mother with her fabulously successful series of children’s books. Her role was an unusual one—part agent, part collaborator—and her level of involvement remains a topic of bitter controversy among Little House fans, many of whom are ferociously protective of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s legend.

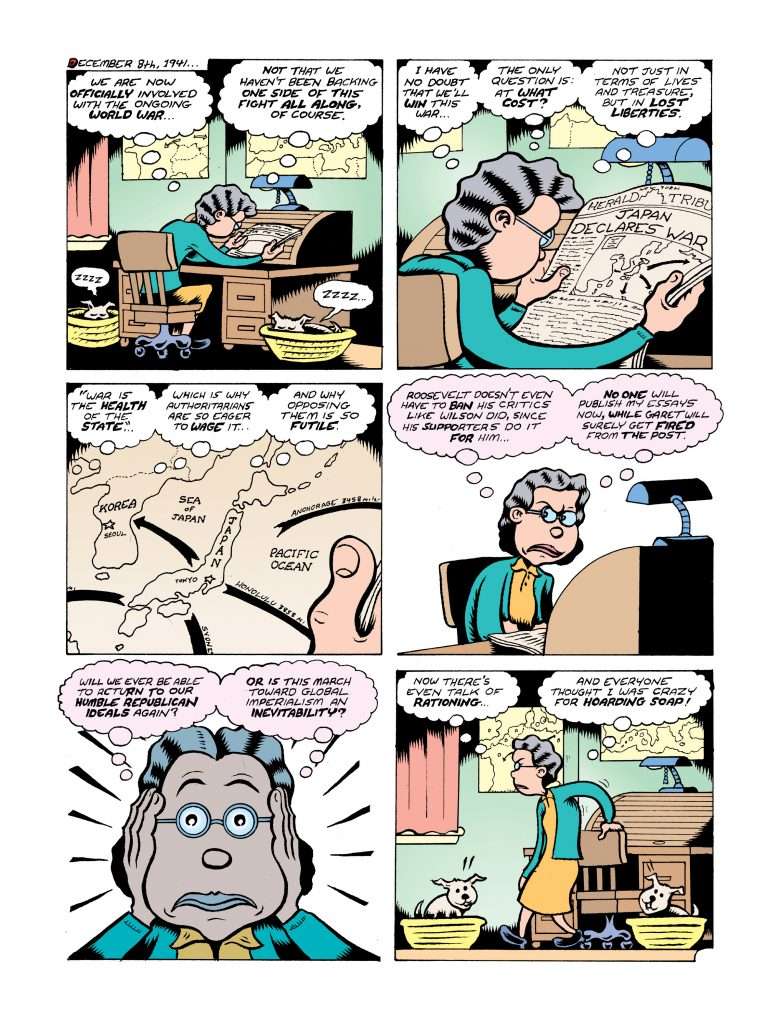

During that same period, under her own byline, Lane was a successful novelist and one of the most popular fiction writers for the Saturday Evening Post, a leading bastion of anti-Roosevelt, anti-New Deal sentiment. Lane worked with proto-libertarian editor Garet Garrett until he was no longer welcome at the publication, which reversed its stance after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

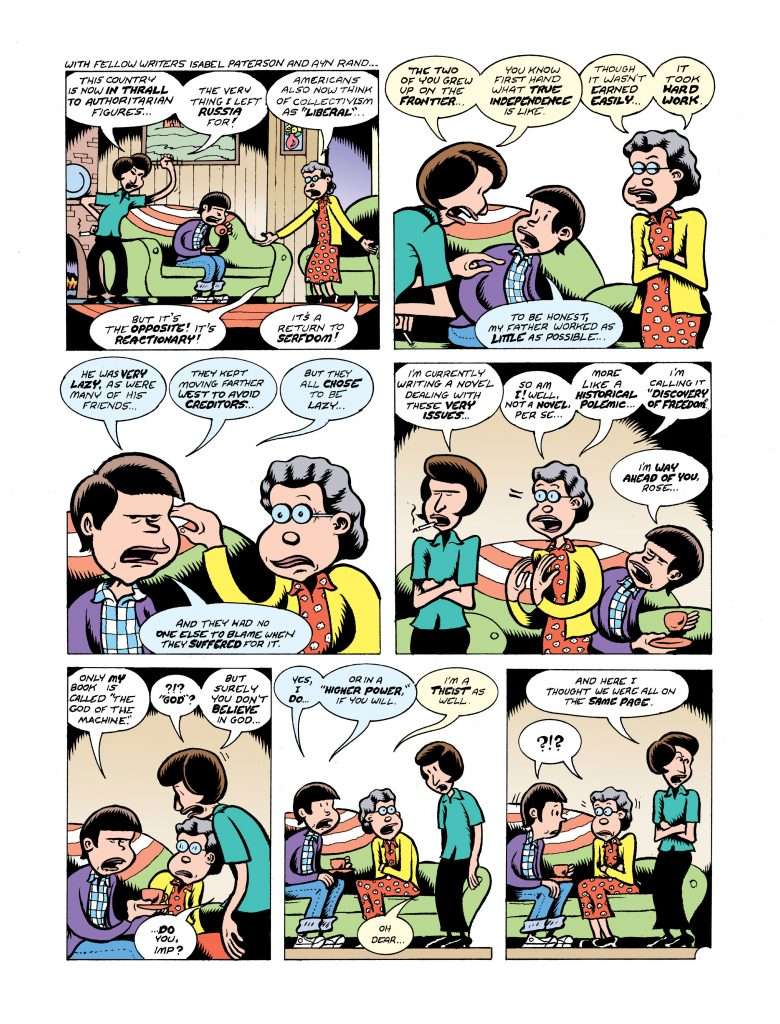

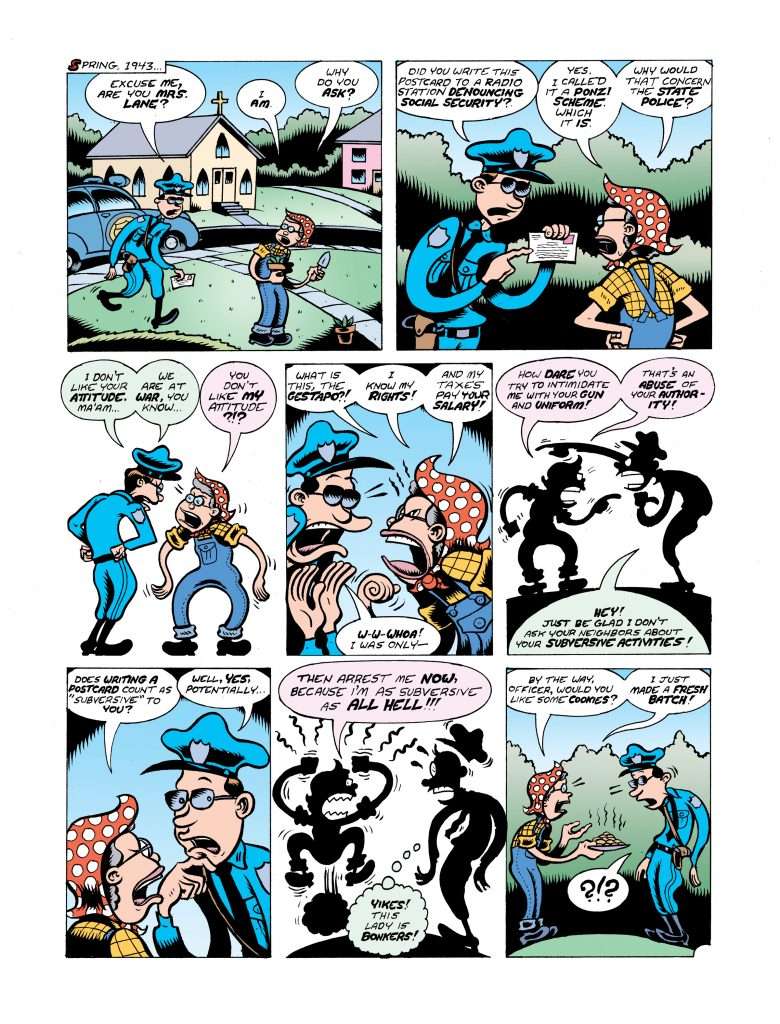

As war approached and the state grew, Lane saw her vision of old-fashioned American liberty on the ropes. In response, she produced one of the ur-texts of the modern American libertarian movement, 1943’s The Discovery of Freedom, a song of praise to human growth and political liberty’s role in furthering it.

Lane was a revolutionary; while believing America’s experiment in liberty arose organically from its frontier experience, she thought the American model could and should spread beyond the nation’s borders. America “is a totally new world,” she wrote. “This new world is an intricate interplaying of dynamic energies, a living network enclosing the whole earth and linking all human beings in one common effort, one common fate.”

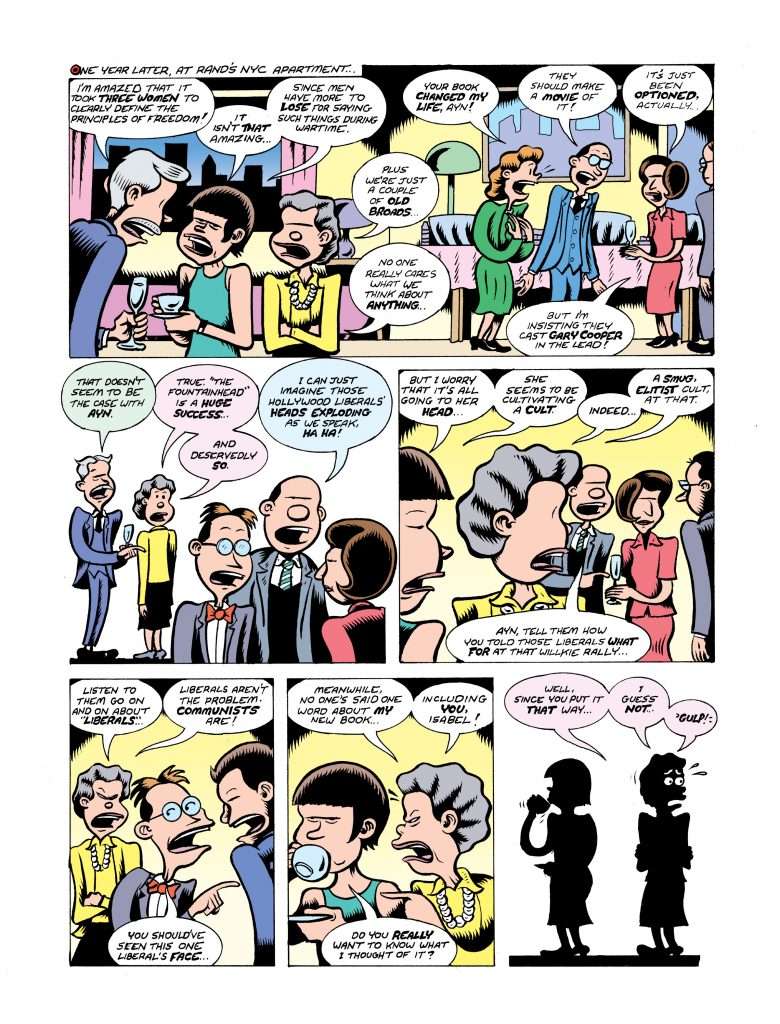

In addition to The Discovery of Freedom, 1943 saw the publication of Isabel Paterson’s The God of the Machine, a nonfiction treatise on the nature and effects of liberty similar to Lane’s, and Ayn Rand’s breakthrough novel of individualism, The Fountainhead. As the journalist John Chamberlain put it, the three friends, “with scornful side glances at the male business community, had decided to rekindle a faith in an older American philosophy. There wasn’t an economist among them. And none of them was a Ph.D.”

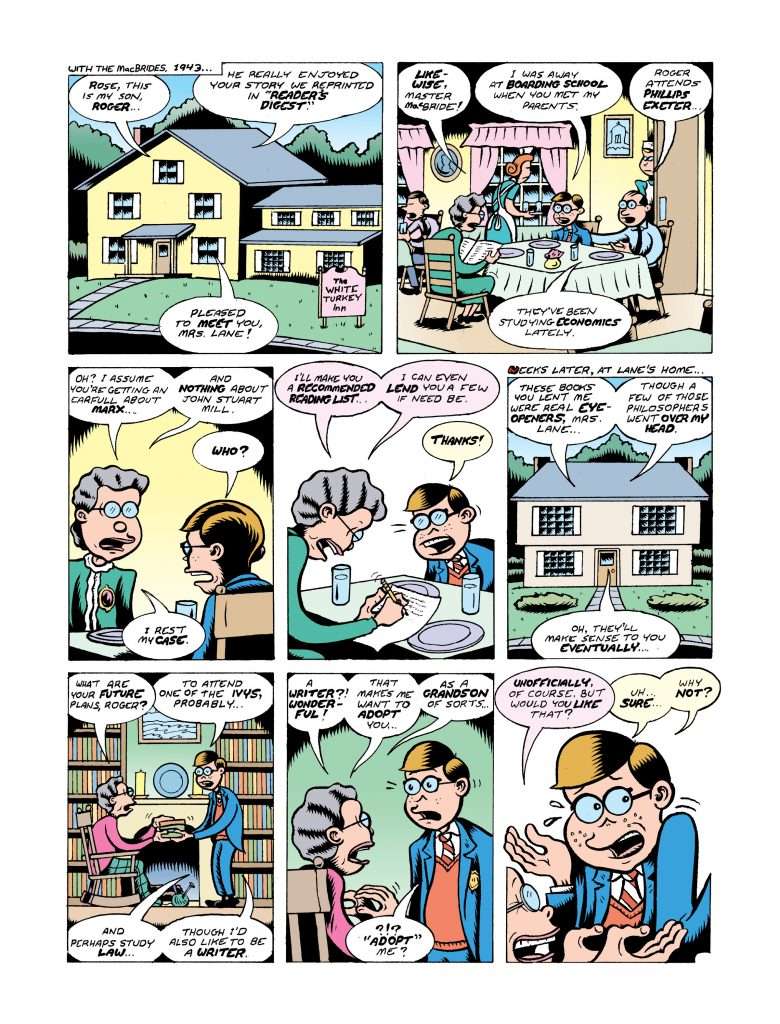

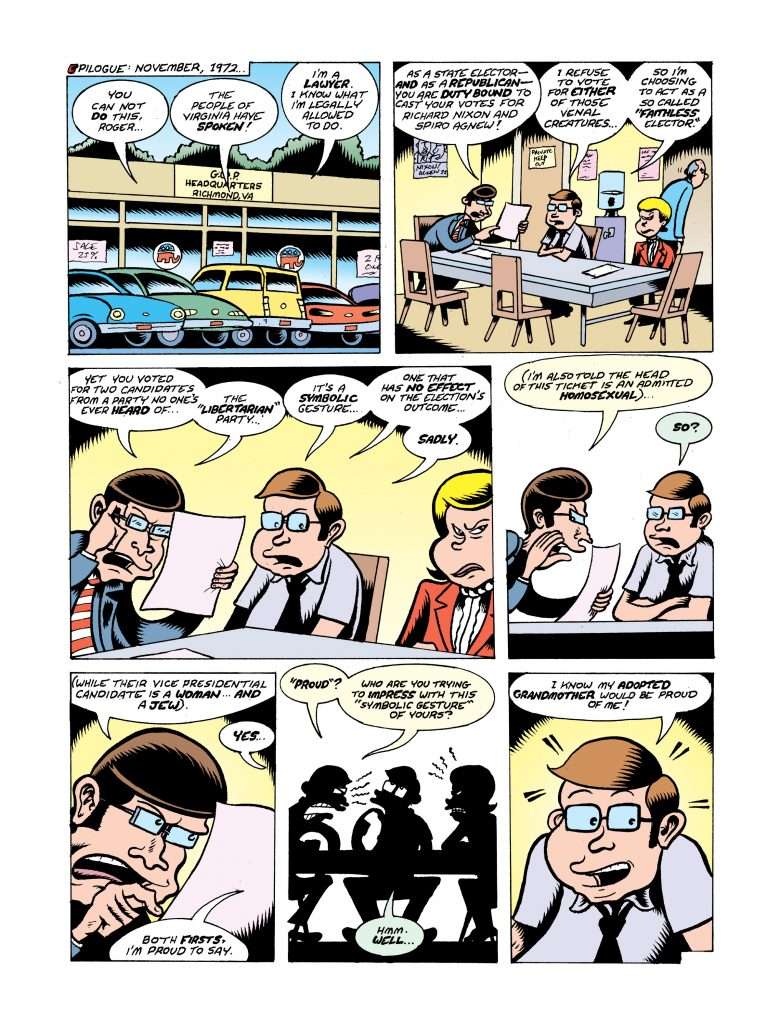

The Little House books remain part of the American canon, with the Wilder family still standing as the template of the self-sufficient pioneer spirit. Lane herself was childless, but she had a habit of quasi-adopting young people, one of whom went on to change the political history of libertarianism: her “grandson,” the eventual Libertarian Party presidential nominee Roger MacBride. Though her own writing is now less well-known, Lane undeniably served as an intellectual foremother to a foundational generation of mid-century libertarian educators and activists.

—BRIAN DOHERTY

The following pages are excerpted from Peter Bagge’s graphic novel Credo: The Rose Wilder Lane Story by permission from Drawn & Quarterly. © 2019 Peter Bagge

from Latest – Reason.com http://bit.ly/2ISKC7y

via IFTTT