It may be among the more unusual medical interventions in recent history. Over the past two years, researchers have been diving beneath the waves in South Florida and applying antibiotic goop to thousands of coral colonies infected with a mysterious and lethal disease.

The efforts are part of an unprecedented collaboration among conservation groups, researchers and biologists, several federal and state government agencies, the Smithsonian, Disney, aquariums around the country, special forces veterans, citizen-scientists, and volunteer scuba divers to save America’s only barrier reef.

Florida’s coral reefs are in deep trouble. Over the past seven years, an infection called Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD) has swept through the 225-mile length of Florida Reef Tract, from north of Miami to Key West, with a lethal speed that stunned conservationists. The disease killed a gigantic, locally famous colony of Mountainous Star coral called “Big Momma,” which had up to that point survived 330 years of hurricanes and industrialization, in a few months. It’s since popped up in 19 other Caribbean countries.

And the disease couldn’t have come at a worse time for Florida’s ailing reefs, which were already in steep decline due to four decades of overlapping environmental pressures.

“If you take the Atlantic Caribbean area, the Keys were the pinnacle,” Mike Goldberg, the owner of Key Dives, a dive charter company in Islamorada, Florida, says. “When it came to coral, when it came to fish life, it had the most volume and variety. Having made over 10,000 dives in various places around the world and in the Caribbean—lived there for about 14 years—there was really nothing that compared.”

A 1962 National Geographic cover story on John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park in the Florida Keys (the magazine’s first-ever underwater color cover, in fact) showed vibrant fields of hard corals.

By the time SCTLD arrived, 97 percent of that historical reef cover was already dead. Scientists worried this new threat could deliver a killing blow to what was left of a once-magnificent ecosystem.

But now there’s preliminary evidence that antibiotics can save some of the most important corals left, and an impressive restoration effort is underway to breed and plant corals back onto the reefs where they once thrived. The decline of Florida’s reefs is a sad story, but if these current efforts can reverse that trend, it will be one of the largest and most innovative public-private environmental successes in American history.

How To Treat Sick Corals

Erin Schilling, a researcher at Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Institute of Marine Science, recently returned from a trip to Dry Tortugas National Park, on the far southwestern tip of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

The Dry Tortugas were the last spot in the Florida Reef Tract that hadn’t been hit by SCTLD yet, and because of its isolation, everyone hoped it would remain untouched. However, the disease arrived this June.

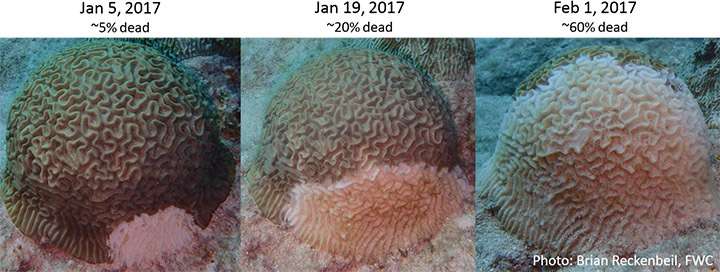

Scientists still don’t know exactly what SCTLD is—a virus or a bacterial infection or possibly a combination of both—or even how it spreads. The disease is such a threat because it targets slow-growing stony corals—boulder-shaped species such as star and brain corals. Those are the literal foundation of reef ecosystems, creating the 3D structures that shelter and sustain other species. Unlike past coral diseases that have run through Florida’s reefs, SCTLD doesn’t appear to wax and wane seasonally, and, when untreated, the disease has a devastating 80 to 100 percent mortality rate for the 20 or so species it affects. It starts as a white patch that expands across a coral colony in a matter of months, sometimes weeks, leaving behind nothing but a bleached skeleton.

The good news is Schilling says she and other research divers treated 6,000 corals at the Dry Tortugas with antibiotic paste to protect them from SCTLD.

Schilling published research this April showing positive results for treating Great Star Coral colonies with the common antibiotic amoxicillin. “It has a really high rate of success in treating what we call an individual lesion, basically white spots where the corals are losing tissue,” she says.

Nova Southeastern University researcher Dr. Karen Neely published more research this August reporting that amoxicillin is also effective at treating long-term and repeat infections.

“In my study we only treated them once, and we saw that they could still get the disease again, or maybe continued having the disease, but [Neely] has even been able to show that sometimes after a couple of treatments, it seems like they are able to heal completely,” Schilling says.

Scientists began using antibiotics in 2019 to try and slow the disease’s march across reefs. It was a gamble, since they didn’t know what side-effects it would have on the corals or nearby wildlife, but the alternative outcome was clear.

“If we do nothing, the corals will just keep dying,” Shilling says. “It’s a grim enough situation that definitely needs a drastic response. Hopefully this will also work well for areas where the disease is still newer. If we’re able to keep understanding how this treatment works, it can be helpful in areas where the reefs haven’t been as impacted yet.”

The results of doing nothing would also be disastrous for the tourism-dependent economy of the Florida Keys. World-class fishing and scuba diving attracts millions of people to the Keys every year. According to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, the reefs in southeast Florida are valued at $8.5 billion and sustain 70,000 full- and part-time jobs. The barrier reef, as the name implies, also protects the Keys from hurricanes and major storms by soaking up wave action that would otherwise batter the low-lying islands.

Diving underwater and manually applying goop to corals is an expensive, labor-intensive, and time-consuming method, though, and it’s ultimately only a stopgap measure.

Andy Bruckner, research coordinator at the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, says the goal is to save the most valuable corals, from a reproduction standpoint, and reduce the amount of pathogens in the water.

“The interventions right now are really challenging,” Bruckner says, “We know that we can’t save entire reefs by doing that, so we have to have a more holistic approach.”

Noah’s Ark for Corals

Before conservationists began experimenting with antibiotics, the outlook was so bad that several state and federal agencies created a Coral Rescue Team to collect specimens for a gene bank, in case some species were wiped out entirely.

The team started out with day trips, but the disease was spreading so fast that they turned to a live-aboard cruise vessel, allowing them to spend multiple days at a time on the water collecting endangered corals.

The problem was they had nowhere to keep thousands of pieces of living coral. The rescue team reached out to the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, the only facilities with the expertise and equipment to keep the corals alive.

“The stark reality is that if the Rescue Team cannot fully develop and execute the Rescue Plan within a very short time frame, one third of the coral species that are found in Florida will become ecologically extinct,” Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute Director Gil McRae warned, according to The Washington Post.

One species, pillar coral, was critically endangered in Florida before the disease struck. Pillar corals are now “functionally extinct” in the Florida Reef Tract, according to a May paper in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science; the remaining individuals are so far apart that they can’t reproduce.

There’s hope, though. In 2019, scientists at a Tampa aquarium announced that after two years of work, they had induced pillar corals to spawn in a laboratory for the first time ever, collecting 30,000 coral larvae and potentially ensuring the future of the species in Florida waters.

There are now Florida corals being held in 20 aquariums across 14 states. The next phase is getting the children and grandchildren of those corals back onto the reef.

An Army of Volunteers and a Lot of Glue

In 2019, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which has authority over the protected waters inside the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, launched “Mission: Iconic Reefs,” a 20-year plan to try to restore seven of the most notable reefs in the Keys. The plan calls for growing and out-planting roughly 500,000 corals. Bruckner calls it “the largest restoration effort that’s ever been attempted anywhere in the world for coral reefs.”

To accomplish this, NOAA is relying on several ocean nonprofits, like Mote Marine Laboratory, Reef Renewal, and the Coral Restoration Foundation (CRF), to do the heavy lifting. The CRF maintains large underwater nurseries where it grows critically endangered staghorn and elkhorn corals. Pieces of corals are strung up on PVC “trees,” that are regularly cleaned by volunteer divers to keep them clear of algae. When the corals are big enough, they’re transported to one of the several reefs.

Planting coral underwater is both tough and delicate work, especially when you’re getting pushed back and forth by surge. Divers use chisels to scrape clean patches of ocean hardbottom before applying an epoxy and essentially gluing pieces of coral down.

So far, the CRF says it has out-planted 130,000 corals back onto the reefs since 2007 with the help of volunteer divers from around the world.

Mike Goldberg, the dive shop owner, also started a local nonprofit called I.CARE that works specifically on the reefs offshore of Islamorada.

“The reason why we got started was not only to restore the reef, but to involve the largest workforce that I believe is out there, and that’s the recreational dive community,” Goldberg says.

Goldberg says I.CARE volunteers have out-planted about 2,000 corals back onto the reefs since the program began in January.

Another partner in the Florida Coral Rescue Project is Force Blue, a nonprofit that gives special forces combat veterans what it calls “mission therapy,” the chance to do some relaxing diving with a purpose. For the past two years, the National Football League has partnered with Force Blue to restore a football-field size coral reef for Super LIV and Super Bowl LV.

Conservationists can’t control two of the most important factors for coral health, water quality and water temperature, but the hope is to at least give the corals a fighting chance. Because corals can propagate asexually, essentially cloning themselves, as well as through spawning, they can be split into fragments that then grow into new, genetically identical colonies. This allows researchers to not only preserve and grow specimens of wild corals, but to experiment and select for ones that are more resistant to disease or tolerant of extreme water temperatures. Fragments of those hardier individuals can then be planted back out in the wild.

As part of the holistic approach that Bruckner mentioned, the initiative also plans to reintroduce “grazer” species of animals, like king crabs and spiny urchins, which eat algae that can crowd out slower-growing corals. Urchins used to fill this role in the Florida Keys, but in the 1980s, a disease practically wiped out the local population.

Because coral grows so slowly, it will be a long time before anyone can say how well the restoration efforts are working, and even longer, maybe generations, before the reefs potentially return to their former glory.

“It’s going to take decades of work,” Goldberg says, “but there will, in my opinion, be a day where we are successful.”

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3vl1md6

via IFTTT