Former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin was convicted of murder and manslaughter last April for killing George Floyd by pinning him facedown to the pavement for more than nine minutes, an incident that triggered nationwide protests. Chauvin, who was sentenced to 270 months in prison after those convictions, pleaded guilty in December to violating 18 USC 242 by depriving Floyd of his constitutional rights under color of law. The three officers who were with Chauvin during Floyd’s arrest in May 2020 are now on trial in federal court, charged with violating the same statute by failing to intervene or render medical aid.

In opening statements yesterday, the prosecution and the defense presented dueling portraits of three men who either callously disregarded Floyd’s pleas for help or understandably deferred to a superior officer in a volatile and potentially dangerous situation they were unable to handle on their own. Yesterday and today, the jury heard testimony from FBI forensic media examiner Kimberly Meline, who presented videos of Floyd’s arrest and the aftermath, and Christopher Martin, the cashier at the store where Floyd allegedly used a fake $20 bill to buy cigarettes, the incident that ultimately led to his death.

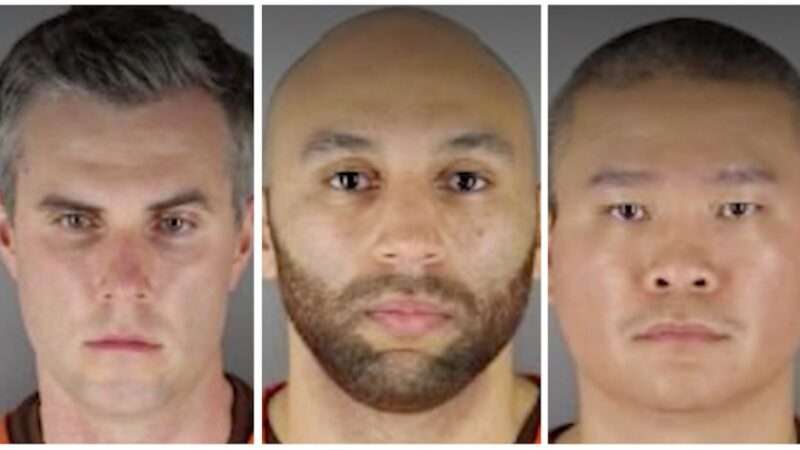

The challenge for federal prosecutors is proving beyond a reasonable doubt that the officers not only neglected their legal duties but did so “willfully.” Officers J. Alexander Kueng and Thomas Lane, both rookies at the time, helped restrain Floyd as he repeatedly complained that he could not breathe. Lane held Floyd’s legs, while Keung applied pressure to his back. Officer Tou Thao was tasked with managing a group of bystanders who were increasingly alarmed by Chauvin’s treatment of Floyd, warning that his life was in danger.

“For more than nine minutes, each of the three defendants made a conscious choice over and over again not to act,” federal prosecutor Samantha Trepel told the jury. “They chose not to intervene and stop Chauvin as he killed a man slowly in front of their eyes on a public street in broad daylight.”

As Chauvin’s lawyer did during his state trial, the defense attorneys urged the jury to consider factors that were not captured in the horrifying videos of Chauvin kneeling on Floyd’s neck. Kueng and Lane had unsuccessfully tried to force an agitated Floyd into the back seat of their patrol car after arresting him for using a counterfeit bill. “He was all muscle,” said Earl Gray, Lane’s lawyer. “These two rookies simply could not get this fellow in the back seat and were clearly doing something wrong. So what does Chauvin do? He takes over and he grabs the guy and he puts him on the ground.”

Gray suggested that Floyd, who seemed to be intoxicated, was exhibiting “superhuman strength”—a claim that Chauvin’s defense also deployed. Former police officer Barry Brodd, testifying as a use-of-force expert during Chauvin’s trial, averred that “drug-influenced” suspects “don’t feel pain” and “may have superhuman strength”—an old canard with racist roots that police tend to drag out when they are accused of using excessive force.

Kueng’s lawyer, Thomas Plunkett, emphasized that he was working just the third shift of his career that day, when he was “confronted with a complex, rapidly unfolding set of circumstances.” Plunkett argued that Kueng had received “inadequate training” and suggested that he was in no position to question Chauvin, his training officer.

Thao’s lawyer, Robert Paule, argued that the officer, who had been employed by the Minneapolis Police Department for about 11 years, had his hands full as “a human traffic cone” standing between his colleagues and a group of six to 10 witnesses. In Trepel’s telling, the outraged reactions of those onlookers, far from an extenuating circumstance, showed that the defendants should have known Chauvin’s behavior was beyond the pale. “After Mr. Floyd lost the ability to speak, the people on the sidewalk stood up for him,” Trepel said. “They understood just by seeing his body go limp, listening to his words and then listening to his silence that, unless somebody changed what was happening, he would die.”

While Thao may not have had as clear a view of what was happening as Kueng and Lane did, his responses to the bystanders’ objections made it seem as if he did not really care. He initially appeared to make light of the situation, saying, “This is why you don’t do drugs, kids.” Thao echoed the other officers’ false assurances about Floyd’s condition, saying, “He’s talking, so he’s fine.”

A man who said he had trained at the police academy repeatedly questioned that judgment and berated Thao for not intervening: “That’s bullshit, bro. You’re fucking stopping his breathing right there, bro….You’re a bum for that, bro.” A woman who identified herself as a Minneapolis firefighter told Thao, “You should check on him… He’s not responsive.” Thao, the “human traffic cone,” disregarded all such warnings, ordering the bystanders who stepped into the street back onto the sidewalk.

Lane twice suggested that, consistent with what police are taught about the risk of “positional asphyxia” during prolonged prone restraints, Floyd should be turned from his stomach onto his side. “The medical aid that would have saved George Floyd’s life was as simple as that—turning George Floyd on his side so his heart kept beating,” Trepel said.

Lane’s suggestions, which Chauvin rejected, imply that Lane recognized Floyd was in danger, although they also indicate that Lane was more concerned about Floyd’s welfare than Chauvin was. By contrast, Trepel portrayed Kueng, based on the video record, as idly distracted by gravel in the tire of a police car as Floyd begged for his life.

The extent and nature of the defendants’ indifference are relevant in deciding whether they acted “willfully” in the context of 18 USC 242. In the 1945 case Screws v. United States, the Supreme Court held that willfulness requires either that the defendant had “a specific intent” to deprive someone of his constitutional rights or that he acted with “open defiance or in reckless disregard of a constitutional requirement.” Federal appeals courts applying that standard have reached somewhat different conclusions.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit, for example, has said willfully means “the act was committed voluntarily and purposely with the specific intent to do something the law forbids”—i.e., “with a bad purpose either to disobey or to disregard the law.” The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit, by contrast, approved instructions saying jurors could “find that a defendant acted with the required specific intent even if you find that he had no real familiarity with the Constitution or with the particular constitutional right involved.” A 2020 report from the Congressional Research Service notes that “the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the willfulness requirement has resulted in what some view as a significant hurdle to bringing Section 242 claims.”

In addition to the federal charges, Kueng, Lane, and Thao face state charges of aiding and abetting Chauvin’s crimes, which may be easier to prove. After the state charges were filed, Ted Sampsell-Jones, a professor at Mitchell Hamline School of Law in St. Paul, noted that they are “legally valid under Minnesota law” but “rely on some fringe doctrines of accomplice liability.” Those doctrines, he added, “have long been criticized by progressive reformers” because they “create expansive strict liability for minor participants in group crimes.”

The post Did These Three Officers 'Willfully' Deprive George Floyd of His Constitutional Rights? appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3u0EKjs

via IFTTT