This is the fourth post in series on the Tibetan Uprising. This one is about 1958, when the Chinese communists attempted to reconquer the vast areas that the Tibetans had liberated in 1956-57. In June, the unified national Tibetan resistance was proclaimed: the Chushi Gangdruk.

Post 1 covered Tibet before the 1949 Chinese invasion, including the Tibetan government’s refusal to heed the 1932 warning of the Dalai Lama to strengthen national defense against the “‘Red’ ideology”. Post 2 was the Chinese conquest, followed by armed uprising of the people, precipitated by gun registration. Post 3 described how the Tibet Uprising drove the Chinese communist invaders out of most of Eastern Tibet in 1956-57.

These posts are excerpted from my coauthored law school textbook and treatise Firearms Law and the Second Amendment: Regulation, Rights, and Policy (3d ed. 2021, Aspen Publishers). Eight of the book’s 23 chapters are available for free on the worldwide web, including Chapter 19, Comparative Law, where Tibet is pages 1885-1916. In this post, I provide citations for direct quotes. Other citations are available in the online book chapter.

Property confiscation

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) had ordered Tibetan gun registration in 1955, and gun confiscation in 1956. The confiscation demand was repeated in April 1958.

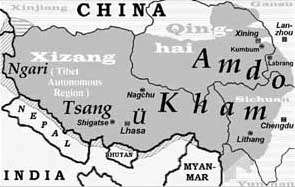

In the summer of 1958, all agriculture and pasturage in Tibet’s two eastern provinces, Kham and Amdo, were fully communized. All land and livestock was confiscated by the communists; the people were forced to work in slave labor gangs.

Most of the food produced by the peasants in Tibet and China was taken by Mao’s regime for export. He used the food for Chinese urban workers (his political base), to buy arms from the Soviet Union, and to export food to Eastern European communist nations to build up his image there. He sent so much food to communist Albania that food rationing was not needed there–quite a rarity in the communist world.

Meanwhile in China and Tibet, government commandeering of so much food caused famines. Carefully rationing food, the communists gave survival level rations to people who could toil the fields relentlessly, and starved the others.

Death by hunger was part of Chinese Communist Party Chairman Mao’s “Great Leap Forward.” It was imposed throughout the “People’s Republic of China” from 1958 onward. But not in the places of Eastern Tibet where the invaders had been expelled. Nor in Central Tibet; the uprisings in Eastern Tibet were preventing the CCP from supplying a large enough army in Central Tibet to impose what Mao considered to be full communism.

Why did members of the Communist Youth League fight the communists?

In both provinces of Eastern Tibet, Amdo and Kham, armed resistance had begun as soon as the Chinese “People’s Liberation Army” (PLA) started appearing in 1949. The Khampa people, who live in Kham and eastern U-Tsang, had revolted en masse in 1955-56, incited by the communists’ orders for gun registration and confiscation. To the north, in Amdo, the 1958 orders for gun and property confiscation convinced many more to revolt.

For many centuries Tibet has had a large Muslim population, which was fully tolerated by the Buddhist theocracy. The PLA invaders were not so tolerant. Some Muslims in Amdo had been fighting alongside the Buddhists against the communists since 1954. (Post 2.) In April 1958 the Muslim Salars of Xunhua county (Amdo) joined the battle. Their interfaith revolt spread to eight townships and lasted one week. The rebellion was joined by 68 percent of local Chinese Communist Party (CCP) members and 69 percent of the Communist Youth League.

A subsequent CCP investigation of Xunhua found that 78 percent of the communists who had joined the rebellion did so because of what the report called “extremely confused ideas about religion . . . preferring to forsake the Party rather than forsake their religion, or even preferring death to forsaking their religion.” Quoted in Jianglin Li, Tibet in Agony: Lhasa 1959 at 57 (2016).

In both China and Tibet, Mao worked to replace traditional religions with one based on himself. Worship of Mao reached its apex as the government-established religion in the late 1960s, during the Cultural Revolution.

Mao always understood that other religions impeded devotion to him. In 1954-55 the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama (second-ranking) spent several months in Peking, as Mao’s guests. Mao was an affable host, and doted on his young visitors.

Mao told the Dalai Lama, “I understand you well. But of course, religion is poison. It has two great defects: It undermines the race, and secondly it retards the progress of the country. Tibet and Mongolia have both been poisoned by it.” Dalai Lama, My Land and My People 117-18 (2006).

More fighting in Amdo

An Amdo rebellion in Tsikorthang county was estimated to involve 10,840 Tibetan fighters, including 1,020 monks and nuns. The Chinese PLA deployed an infantry regiment in July 1958. Five months later, the PLA regiment claimed victory and withdrew, while the surviving Tibetans escaped to the hills. The Chinese soldiers had been told that the Tibetan people viewed them as liberators. But as a PLA commander indignantly reported to his superiors, the Tibetan masses supported the rebels, feeding them, sheltering them, and concealing them.

A June 1958 report by the provincial Communist Party Committee to the party center estimated there were a hundred thousand rebels in Amdo. They came from 240 tribes, and constituted one-fifth of the province’s Tibetan population. The uprisings involved 6 prefectures, 24 counties, and 307 monasteries.

In Lhasa, a unified national uprising is organized

The capital city Lhasa (Central Tibet) and environs were becoming crowded with refugees. About ten to fifteen thousand were Chinese who had fled Maoism in China and were contentedly making a living running small shops. The CCP deported them back to China. Then the communists announced a program to register the refugees from Kham and Amdo who were living around Lhasa. They too would be deported unless they had written permission from the CCP to live in Lhasa. Some of them then disappeared, including those who left to join the resistance forces; many already had arms and combat experience from the earlier revolts in Eastern Tibet.

As described in Part 3, the wealthy Lhasa merchant Gompo Tashi Andrugtsang had spent 1956-57 organizing a unified resistance to the invaders. He decided that it was time to proclaim the all-Tibet resistance army. He sold all his wealth to purchase ammunition and arms—including rifles and handguns from Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Czechoslovakia. His 46 employees were “armed to the teeth and provided with horses” to join the resistance. Gompo Tashi Andrugtsang, Four Rivers Six Ranges: Reminisces of the Resistance Movement in Tibet 59-60 (1973).

In Tibetan Buddhism, being born with wealth, power, or intelligence “automatically came with the moral responsibility of helping other sentient beings less fortunate.” Mikel Dunham, Buddha’s Warriors: The Story of the CIA-Backed Tibetan Freedom Fighters, the Chinese Invasion, and the Ultimate Fall of Tibet 250 (2004).

The new national resistance army was named the Chushi Gangdruk (Gandgrug, Gangrug). It was proclaimed on June 16, 1958, in the Triguthang valley of the Lhoka area–under a hundred miles south of Lhasa.

The full name was Chushi Gangdrug Tensrid Danglang Mak (“the Kham Four Rivers, Six Ranges Tibetan Defenders of the Faith Volunteer Army”). They were also known as Volunteer Freedom Fighters for Religious and Political Resistance (VFF). “Four Rivers, Six Ranges” was a traditional appellation for Kham. The rivers are the Mekong, Salween, Yangtze, and Yalung.

There were twenty to thirty thousand Chushi Gangdruk in Lhoka on proclamation day.

They were farmers, nomads, peddlers, and monks. They carried their own rifles, flintlocks, hunting guns, and swords, and wore their everyday clothes: leather or felt books, assorted caps, and the traditional Tibetan robes, known is chupas . . .

Li, Tibet in Agony, at 69.

The Chushi Gangdruk unfurled their flag: crossed swords on a yellow background. Yellow was the color of Buddhism, which the Chushi Gangdruk defended from communism. The flaming sword belonged to Manjusri, the bodhisattva who sliced through ignorance, which was the root cause of communism. The other sword, a symbol of bravery, was a weapon that Tibetans made themselves.

Back in 1951, the Chinese communists had forced Tibet to sign the the Seventeen Point Agreement, accepting Chinese sovereignty in exchange for Chinese promises, all of which were broken. The pretext for the Seventeen Point Agreement was that Tibet needed to be liberated from Western imperialism. At the time, there were eight Americans or Britons living in Tibet, all of them having permission from the Tibetan government and assisting the government with projects such as radio communication.

The words that the Chinese communists had deceitfully written into the Seventeen Point Agreement were, ironically, followed by the Chushi Gangdruk: “The Tibetan people shall unite and drive out imperialist aggressive forces from Tibet.” Seventeen Point Agreement, § 1.

How the Chushi Gangdruk resistance army operated

To the extent possible, Chushi Gangdruk guerilla units comprised fighters from the same native place or district. Officers were the leading men from their home area; they were not necessarily the most expert in military matters, but they had the confidence and loyalty of their troops, which was essential. Twenty-eight resistance groups joined the Chushi Gangdruk.

The Chushi Gangdruk were acquiring arms from all over. The Tibetan government did not try very hard to prevent them from “stealing” arms from the Tibetan army arsenals. The PLA did try to thwart raids on its own arsenals, but often not successfully. Meanwhile, Gompo Tashi was buying Russian-made rifles and pistols from India, Nepal, Sikkim (at the time, an Indian protectorate, which had been independent until 1950), Bhutan, Pakistan, and China. The Tibetan cabinet, the Kashag, ordered monasteries not to distribute arms to the freedom fighters, but this order was not always obeyed.

With the new arms supplies and unity, the Chushi Gangdruk cut off the three strategic highways south of Lhasa, thwarting PLA mobility. The Prince of Derge was leading his own men in hit-and-run raids on Kongpo (Nyinghci prefecture), an area between Lhoka and Chamdo in Central Tibet. Derge is further east, in Kham, Eastern Tibet. The prince had become a rebel leader after the CCP took all his property and killed his family.

The Dalai Lama

The Chinese communists were outraged at the Chushi Gangdruk. It was clearly a coordinated national campaign, far more so than the local rebellions of earlier years. The CCP commanded the Dalai Lama to deploy the Tibetan army against the Chushi Gangdruk. Directly disobeying a Chinese order for the first time, the Dalai Lama pointed out that if the army were ordered to fight the Chushi Gangdruk, the army would instead join them. The Tibetan cabinet, the Kashag, agreed with the Dalai Lama—well aware that the army might remove the Kashag rather than wage war against the Chushi Gangdruk. Indeed, starting in November 1958, many Tibetan army soldiers deserted to join the Chushi Gangdruk.

The Dalai Lama did issue announcements urging the rebels to lay down their arms, but “the Chinese censors were so heavy-handed, and the messages so clearly written for the benefit of the Chinese, that the freedom fighters could see behind the words. They knew that His Holiness might not approve of their actions, but they took comfort in the knowledge that he was not against them.” Roger Hicks & Ngakpa Chogyam, Great Ocean 105 (1984) (authorized biography).

Strengths of the Chushi Gangdruk

More rebel bands arose and expanded. For example, one group that began with 10 men and 4 rifles grew to 40 families, and then to 300 families. By late 1958, the revolt had become massive. Some Tibetan refugees in India returned to Tibet to join the Chushi Gangdruk. All of the tribes of Kham were resisting in arms. Amdo was in rebellion, and twenty thousand Goloks (a non-Tibetan tribe in Amdo) were fighting too.

The Tibetans had the morale advantage. “PLA troops fought because they were told to.” When the Chushi Gangdruk “drew their swords, they had an image of a raped wife or a murdered father to urge them on. And unlike the Chinese soldiers, they held the ultimate trump card: They had nothing left to lose.” Dunham at 261.

The terrain favored the Tibetans. They knew the rugged mountains well, and the Chinese did not. Their bodies had evolved to thrive in the thin air that exhausted invaders from the lowlands. As in the Korean War, some PLA soldiers deserted at the first opportunity. The Chushi Gangdruk had to discern which self-proclaimed PLA deserters were sincere and which were PLA spies.

To attempt to discredit the resistance, the PLA paid local bandits to pose as rebels and plunder villages. The Chushi Gangdruk worked hard to eliminate the false flag criminals.

Weaknesses of the Chushi Gangdruk

The rebels faced other challenges. Although they were proficient with firearms and swords, most were not trained in guerilla warfare. The CIA-trained leaders, once they returned to Tibet, could disseminate knowledge of tactics and operations, but these trainees were not able to reach or interact with all of the many resistance groups throughout Tibet.

In addition, the resistance was often short of arms and ammunition. As discussed, Tibet before the 1949 communist invasion had lots of firearms, but many of these were flintlocks or matchlocks, far inferior to the bolt action and semi-automatic firearms that had been invented in the late nineteenth century. As for ammunition, many Tibetan families before 1949 had quantities sufficient for ordinary uses—such as hunting, or family and community defense from bandits—but not for protracted guerilla warfare with numerous battles lasting hours or days.

Sharing information among the rebels remained a problem. The only newspapers were published in Lhasa, and they were run by collaborationists and the CCP. Monasteries were information nodes, but even among them, news could only spread by word of mouth, the distance that a man could walk or travel on horseback. “Tibet was a million-and-one informational cul-de-sacs.” Dunham, at 251.

The volunteers were short of equipment for radio communication, which of course hampered coordination. But this was a blessing in disguise. Secret Chinese military documents have revealed that the PLA had cracked the Tibetans’ simple radio encryption codes. Besides that, the PLA had spies inside the Tibetan resistance forces.

The PLA’s numerical strength

The PLA’s biggest advantage was manpower. The Tibetan population was relatively small, perhaps about three million, and so attrition, including from the absence of medical care, gradually wore them down. In contrast, the PLA had no concern for soldiers’ lives, and could easily replace dead soldiers from an inexhaustible supply back in China. As the Tibetans said, if they killed one PLA soldier, ten would replace him. If they killed ten, a hundred would replace them. The overwhelming Chinese advantage was worsened by the Tibetans’ ammunition shortage. They could not afford many shots that did not cause a casualty.

In military history, there are many fighters who were, man for man, superior to their opponents, but who were eventually defeated by sheer force of numbers—for example, the Romans against the barbarian tribes during the last century of the Western Roman Empire, New Zealand’s Maori natives against the invading British in the nineteenth century, or the Germans against the Soviets in World War II.

Massive Chinese reinforcements began arriving in late 1958. By the end of the year, the situation in Eastern Tibet was mostly under control, even though some resistance there would continue for years.

As local uprisings were crushed, the PLA would round up all the able-bodied surviving men, imprisoning them or sending them to a laogai slave labor camp. Their families would be permanently branded as part of the lowest class. “Prominent citizens mysteriously disappeared forever,” even those who had cooperated with the communists. Li, Tibet in Agony at 61-63. “In Yulshui Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture [Amdo], the slaughter created ghost towns and ‘widows villages.’ Young men escaped death by donning their sheepskin jackets inside out as camouflage and hiding among their flocks of sheep.” Id. at 63.

The situation in Central Tibet

Within Central Tibet, the Chushi Gangdruk still had the initiative. In the winter of 1958, their Lhoka force advanced to within 30 miles of Lhasa. The presence of resistance fighters in Chamdo (a Khampa prefecture in the east of Central Tibet) was making travel on the two highways from China to Lhasa impossible except with heavy military escort. The new airport at Lhasa helped the PLA overcome some of the logistics problem.

On November 8, 1958, the PLA’s Tibet Military Command established a militia in Lhasa, consisting of Han whom Mao had exported to Tibet. Quickly, the militia was well organized and well armed. At the PLA garrison next to Lhasa, a buildup of artillery gave the PLA the ability to hit any building in the city and to shut off access to the entire valley.

Now, the Chinese imperial army was ready for the next step: to eliminate the Dalai Lama.

The post Tibet's armed resistance to Chinese invasion appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest https://ift.tt/SJshrIp

via IFTTT