When the deliberately inefficient give-and-take of liberal democracy doesn’t let you shoehorn neighbors into your preferred policy solutions, there are two likely reactions: You decide the coercive state isn’t the right means for achieving your goals and try voluntary means instead, or you conclude that the give-and-take of disagreement and debate is the problem and double down on coercion with the safeguards removed. That second choice in favor of authoritarian end-runs is growing increasingly popular, with environmentalists among the greatest enthusiasts.

“In the Q&A session after every talk I give on climate change, someone will typically raise a rather uncomfortable question: are democracies, given the short-termist nature of electoral politics, fundamentally incapable of tackling the climate crisis?” writes Mark Lynas, author of Our Final Warning: Six Degrees of Climate Emergency, at Persuasion. “Nor is this idea limited to a political fringe. Environmentalist academics with impeccable liberal credentials also occasionally raise the question of whether classic Western liberal democracy isn’t up to the job.”

Lynas goes on to cite recent books, essays, and scholarly papers by environmental advocates suggesting that climate change is such a pressing concern that it justifies government officials steamrolling over limitations on state power and protections for individual rights.

“While, under normal conditions, maintaining democracy and rights is typically compatible with guaranteeing safety, in emergency situations, conflicts between these two aspects of legitimacy can and often do arise,” wrote Ross Mittiga, a political scientist at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, in a paper published in December 2021 by the American Political Science Review. “A salient example of this is the COVID-19 pandemic, during which severe limitations on free movement and association have become legitimate techniques of government. Climate change poses an even graver threat to public safety. Consequently, I argue, legitimacy may require a similarly authoritarian approach.”

The most recent example may have come too late for Lynas to include. On Tuesday, Elected Officials to Protect America (EOPA) held a virtual press conference calling on President Joe Biden to invoke the Defense Production Act (DPA) “to accelerate a clean energy transition for energy security” and, incidentally, “to help Ukraine.” The Ukraine mention, one suspects, was thrown in because the DPA lets the federal government centrally direct the economy for national defense purposes. Then-President Donald Trump stretched “national defense” in 2020 to cover COVID-19, but the EOPA seem to recognize that climate change may be a step too far on its own, hence “Ukraine.”

“The DPA authorizes the president to require businesses to accept and prioritize contracts for materials deemed necessary for national defense, and allows the president to designate materials to be prohibited from price gouging and hoarding,” EOPA helpfully adds on its website.

EOPA, which claims to represent 1,313 elected officials in all 50 states, also wants the president “to go further than activating the DPA,” according to a press release. “It supports a clean energy plan and asks for a Presidential Climate Emergency Declaration under the National Emergencies Act. A declaration will communicate the urgency of the climate crisis and unlock specific statutory powers.” If a law granting semi-dictatorial powers during wartime isn’t enough and you call for a state of emergency to “unlock specific statutory powers,” you just might rank among those who have lost all patience with dissent and democracy and believe something more thuggish is required.

Environmentalists aren’t alone in their frustration at not getting their way through the political process. Famously, on January 6, 2021, a mob of Trump supporters threw a collective hissy fit over their preferred candidate’s loss at the ballot box. And the rot goes deeper still.

“Roughly 2 in 10 Trump and Biden voters strongly agree it would be better if a ‘President could take needed actions without being constrained by Congress or courts,'” the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics found in a September 2021 survey. More than 40 percent of both groups at least somewhat agreed with that sentiment.

In 2020, the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group noted that “one-third (33 percent) of Americans have at some point in the last three years said that they think having ‘a strong leader who doesn’t have to bother with Congress or elections’ would be a good system of government.”

So, environmental advocates aren’t the only people impatient with debate and persuasion. But they are on the leading edge of the illiberal impulse at the same time that they embody the dangers inherent in trying to achieve policy goals through authoritarian means—because authoritarian regimes have a terrible record on environmental issues.

“During the ‘environmental decade’ of the 1960s and 1970s scholars first wondered whether communist states might have developed in an environmentally more sensitive way than capitalist ones,” wrote Douglas R. Weiner in The Cambridge History of Communism, published in 2017. “Most concluded that not only did communist regimes fail to realize the theoretical advantages of a dirigiste system, their careless practices brought about, in the words of Murray Feshbach and Fred Friendly, Jr., an ‘ecocide.'”

“By one estimate, in the late 1980s, particulate air pollution was 13 times higher per unit of GDP in Central and Eastern Europe than in Western Europe,” Shawn Regan of the Property and Environment Research Center commented in 2019 about the old Soviet bloc. “Levels of gaseous air pollution were twice as high as this. Wastewater pollution was three times higher.”

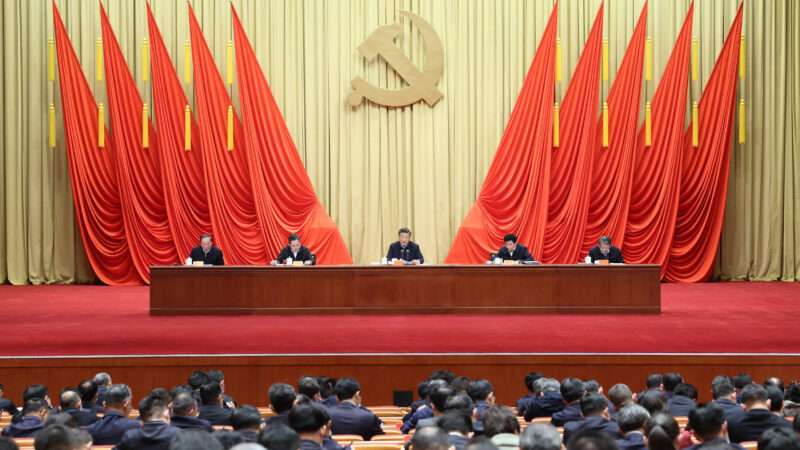

The record of dictatorial regimes hasn’t improved. “The Chinese Communist Party Is an environmental catastrophe,” Richard Smith succinctly observed in a 2020 Foreign Policy article.

That’s especially ironic given that one of the works Lynas cites as championing environmental authoritarianism, The Collapse of Western Civilization: A View from the Future, by Naomi Oreskes and Eric Conway, fantasizes about China’s rulers prevailing over liberal-democratic rivals in managing environmental crisis. It’s more likely authoritarians will cause problems than resolve them.

Ultimately, observes Lynas, “it is the exact opposite of authoritarianism—freedom of speech, open debate, protest, and political advocacy—that has the potential to bring about policies to address the climate emergency.” That same point could be made about every issue that people find compelling. Debate, opposition, and respect for individual rights can save all of us from the worst ideas of policy advocates who often mistake fanaticism for infallibility. Those too impatient to wade through the political process always have the option to abandon coercive government mechanisms and try to achieve their goals through innovation, persuasion, and other voluntary means.

The post Your Favorite Crisis Doesn't Justify a Dictatorship appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest https://ift.tt/ewGIYh9

via IFTTT