Free Speech: A History From Socrates to Social Media, by Jacob Mchangama, Basic Books, 528 pages, $32

Many languages have in-built speech codes: There are levels of formality and informality in address, words that are not to be used in certain contexts, even forms of speech specific to men and women. European languages tend not to carry the levels of baroque distinction found elsewhere, but they still maintain formal and informal registers. English is distinctive in having essentially abandoned them; our you was once the formal/plural form of address (thee being the familiar).

But when we talk about freedom of speech, we usually mean legal restrictions backed up by the state. These too date back thousands of years. Ancient edicts offered strict instructions in who was allowed to say what and to whom. Around 2500 B.C., the Sumerian Code of Ur-Nammu declared that “if a slave woman curses someone acting with the authority of her mistress, they shall scour her mouth with one sila [0.85 liter] of salt.” I’m guessing that she wasn’t allowed to say that slavery sucked either.

With Free Speech: A History From Socrates to Social Media, Jacob Mchangama races through those thousands of years of intellectual and political history to show how distinctive—and how essential—the concept of free speech is. Mchangama, a Danish lawyer, has been an important voice for liberty over the last decade, particularly in the context of Islamic blasphemy claims in Europe. His book is an excellent guide for anyone who wants to know why free speech matters.

For much of European history, the speech being widely policed was heretical or treasonous. (Or both: The divine right of kings meant a fair amount of potential crossover.) As Mchangama shows, early universities were sites of information exchange as well as crackdowns on those people thought to be spreading dangerous views.

These were by necessity elite debates: Most people had no opportunity to read the controversial texts that scholar-monks were troubled over. That started to change with the arrival of the printing press, although that didn’t mean your average reader suddenly got sucked into Thomas Aquinas. As Mchangama points out, the same printing presses that disseminated philosophical tracts “churned out a steady stream of virulent political and religious propaganda, hate speech, obscene cartoons, and treatises on witchcraft and alchemy.”

We see this with every new form of communication. Barely five minutes after the invention of the photograph, someone was taking nudie pics. But the printing press opened doors far beyond smutty woodcuts to new ways of thinking. Martin Luther was not the first to speak out against the church, but he was first to fall on the latter side of the Gutenberg divide. So his ideas spread further, including to those who weren’t readers.

It helped that Luther understood his audience. “The layout and design of his writings became increasingly slick,” Mchangama writes, “and the punchy text was accompanied by illustrations for the benefit of the illiterate who eagerly shared his anti-Catholic memes.”

Not everyone was thrilled with Luther’s takedowns of the pope, and the conflicts of the Reformation brought rapid-fire publications on all sides. As today, legislation raced to keep up with new speech challenging the old order. The result of the print revolution was not just books but newspapers, which spread ideas, fostered commerce, and linked communities. Technology and trade brought ever-more-affordable paper and ink, and also postal systems. Pretty soon you could insult someone from hundreds of miles away.

The political debates that filled pamphlets and newspapers during the Enlightenment could be high-minded and important. But a lot of them weren’t. Pamphlet wars, Mchangama recounts, “quickly descended into an eighteenth-century version of flaming, trolling, name-calling, motivated reasoning, and butchering of straw men.”

In the context of this text culture, the French Revolution sent shockwaves across Europe, as panicked monarchs suddenly wanted to crack down on republican ideas spreading among their subjects—the kind of reactive legislation that marks the history of free speech. Over the 19th century, a more laissez faire attitude toward speech slowly evolved in Europe (with some hiccups), though some of the more traditional clerical perspectives would hang on longer in the Catholic countries. But nowhere in Europe went as far with the concept of free speech as America did.

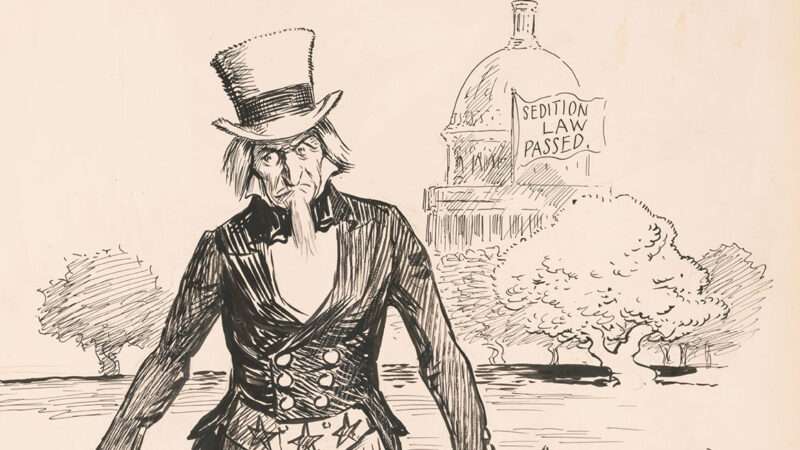

Here too there were still limits, as high-minded liberalism brushed up against political reality. The kind of speech that the Founders wanted to keep under control was often libel and slander, and the British tradition of a relatively highly developed civil-suit culture was a way of dealing with that. A more heavy-handed approach appeared not long into the federal experiment, with the short-lived Sedition Act of 1798. It allowed the deportation or imprisonment of people who produced “false, scandalous, or malicious writing” against the government of the United States. The act expired three years later, but it influenced the debate over what speech should be allowed.

Another major stumbling block came with the conflict over slavery. Southern states sought to ban and punish abolitionist literature, passing laws casting it as incendiary. “Ironically,” Mchangama notes, “this included the idea of group libel—a progenitor of modern ‘hate speech’ laws, which protected specific groups from defamatory statements. Senator Calhoun complained that the abolitionist petitions ‘contained reflections injurious to the feelings’ of Southerners who were being ‘deeply, basely and maliciously slandered.'” It would be hurtful for the poor slaveholders to hear that people thought they were bad.

Despite the promises of the First Amendment, America’s uneven approach to free expression continued over the decades. In 1918, the Sedition Act cracked down on speech seen as defaming the government, or the military, or the flag, or speech that was otherwise deemed disloyal. (The American Civil Liberties Union was established in 1920 in response.) It wasn’t only political speech that was regulated. The Comstock Act of 1873 banned “obscene” publications, which to the authorities meant not only pornography but also family-planning pamphlets. The birth control rules were not struck down until Griswold v. Connecticut in 1965.

On a global level, the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century brought new challenges. Despots, naturally, are not big fans of free discourse. But how should democracies respond to despots? Some countries, like Germany, have passed laws against sharing Nazi propaganda, restricting free speech in the name of preserving freedom. But is making something off-limits really the best way to address it?

Mchangama details the post-war wrangling over the U.N.’s Declaration of Human Rights and its clause proclaiming the right to free expression. This was always going to rub painfully against people whose religious beliefs demand punishment for blasphemers, especially as globalized mass communications transmitted unwelcome ideas from one region to another. The fatwa against Salman Rushdie was the first major case exposing this tension. The challenge persists as governments try to balance their stated commitments to free speech with laws against spreading hate.

Meanwhile, the secular world has its own forms of blasphemy. As our politicians and tech gods talk about cracking down on “disinformation,” I get the sneaking suspicion that they don’t just mean Sandy Hook truthers—they mean political ideas they don’t like, the stuff they called “sedition” in 1798. Once the government is allowed to silence speech, the net of justification always broadens.

The post Speaking Freely Through the Ages appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest https://ift.tt/tuLShdp

via IFTTT