Via GoldMoney Insights,

Brent crude oil prices rallied $100/bbl since the lows in 2020. This reflects very tight fundamentals, where petroleum inventories are at extremely low levels relative to consumption and supply is struggling.

The war in the Ukraine has worsened the near-term supply outlook further.

The current conditions in the oil market are critical and we could see real oil shortages by this summer if the disruptions to Russian oil supplies persist or even worsen. This would put even more upward pressure on current prices and overall inflation. However, we think an even bigger and more permanent issue has been brewing in oil markets for years and it is finally filtering through to the back end of the forward curve.

Longer dated prices have broken out of their 5-year range and have been moving up relentlessly.

We think the oil markets finally begin to understand that a lack of investments in large oil projects over the past years is threatening supply over the entire next decade, at a time when demand will still be growing as the electrification of the transportation sector will not impact demand meaningfully for years to come.

The sharp upward moves in oil prices amidst a broader commodity prices rally have pushed realized inflation and near-term (0-2y) inflation expectations up strongly. But inflation expectations beyond that time horizon have proven to be resilient. So far the back end of the oil curve moved up only $15/bbl. However, we think that once back end prices are moving in a similar fashion to what we currently witness in the front, longer term inflation expectations will likely begin to move up too.

In this two part report, we look first at how we got to the current price environment and in the upcoming second part we do a deep dive into the long term outlook for crude oil markets.

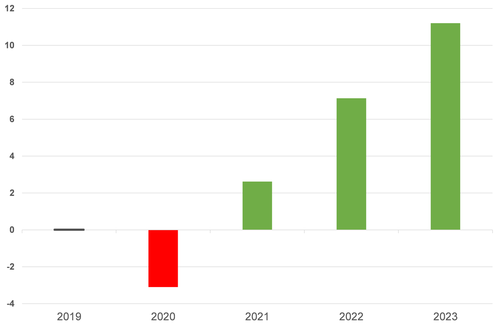

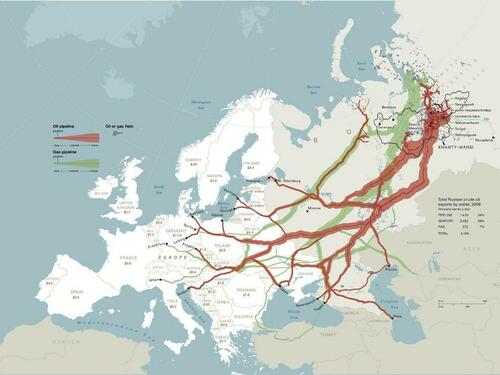

Oil prices have reached the highest levels since the all-time highs in 2008. The most obvious explanation for the sharp rally is the military conflict in Ukraine and the threat of a loss of Russian oil supplies. However, oil prices are only up $20 since the war started a month ago. In fact, Brent crude oil prices have been rising relentlessly ever since the lows of around $20/bbl we saw during first lockdowns in spring 2020, to $95/bbl just before the invasion (see Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Oil priced rallied close to $80/bbl from their lows before the Ukraine invasion started

$/bbl

Source: Goldmoney Research

While everybody points to the Ukrainian conflict to explain high prices, just a month ago there was a vigorous debate among analysts, media, and politicians about what was behind the fact that oil had broken out of the $60-80 range it has mostly been trading in for the past years (except the quick lockdown crash in early 2020) and started to rally relentlessly. Was it exceptional demand, reflective of a strong economy coming out of the pandemic as some claimed? Or rather supply bottlenecks, similar to the supply issues that plagued many other industries at the moment. Was it OPEC? Or just broad based inflation filtering into oil, given that almost any other commodity has shown similar or even higher price increases over the past two years.

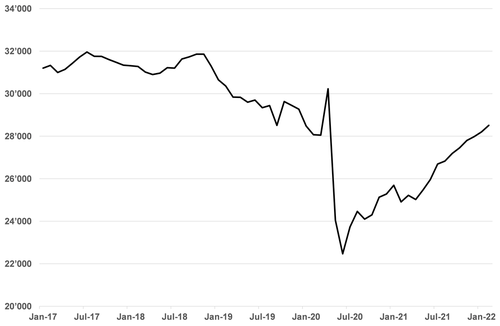

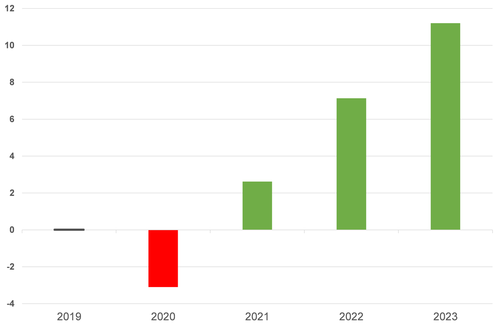

First, it wasn’t (and still isn’t) exceptionally strong demand. While global oil demand has significantly recovered from the lows in spring 2020, for 2022 it is still slightly below where it was before the pandemic (see Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Global oil demand has strongly recovered but remains below pre-pandemic levels so far

Mb/d, 12 month moving average, change vs 2019

Source: Goldmoney Research

This means it is lagging overall economic activity, which, according to the World Bank and the IMF, is roughly 7% higher in 2022 than it was in 2019 (see Exhibit 3). A rule of thumb is that global oil demand grows roughly at the rate of GDP -2% efficiency gain per annum. In this case, a 7% GDP growth over two years plus 2% compounded efficiency gains would suggest that oil demand – if it wasn’t for the remnants of the pandemic – should be roughly 1 million b/d above 2019 levels.

Exhibit 3: cumulative changes to real GDP vs 2019

%

Source: IMF

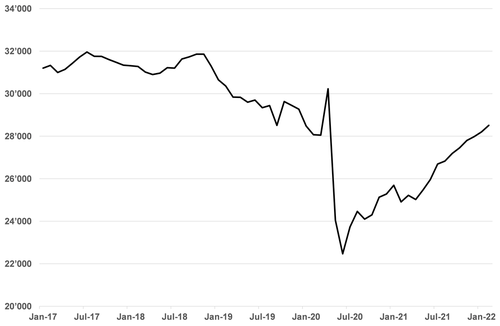

The reason why oil demand is lagging is mostly due to the lack of jet fuel demand. Jet fuel accounts for about 10% of global oil demand and air traffic is still quite a bit lower than it was before the pandemic. Globally commercial air traffic is still down 20% vs. pre-pandemic levels according to Flightradar24, a site tracking commercial air traffic (see Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4: Commercial flight activity is still 20% below pre-pandemic levels

Source: Flightradar24.com

During the first wave of the Covid19 pandemic, oil demand crashed like it never had before. At it’s lowest point, oil demand was down 20%. As a comparison, during the great recession of 2008-2009, oil demand was down just about 3.5% at any point in time (see Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5: The demand destruction from the lockdowns dwarfed the demand destruction from the recession that followed the 2008-2009 credit crisis

Kb/d year-over-year

Source: Goldmoney research

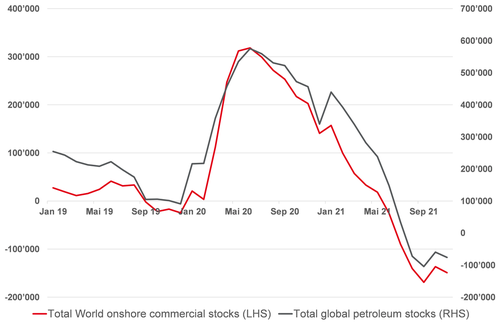

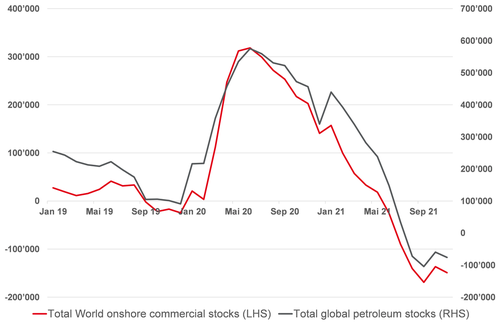

This demand destruction in early 2020 lead to a massive build in global inventories. Global total petroleum stocks rose at the fastest rate and reached their highest levels in history as producers didn’t curb production fast enough (see Exhibit 6).

Exhibit 6: Total commercial petroleum’s stocks, including floating storage, reached their highest levels in history in 2020

Kb

Source: Goldmoney Research

Which is where OPEC+ comes in. After taking a very different direction during the February meeting (Saudi Arabia, upset about Russia’s refusal to agree to production cuts, ramped up production to all-time highs and flooded the market with crude, promptly crashing prices), OPEC+ swiftly decided to act when it became clear what the global lockdowns did to demand. The group cut oil production by around 10 million b/d (see Exhibit 7). And surprisingly, all group members stuck to their quotas since that decision was made.

Exhibit 7: OPEC swiftly cut production by a record amount when the effects of the lockdowns on demand became clear

Kb/d (OPEC crude oil only, auxiliary states in OPEC+ not included)

Source: Goldmoney Research

Subsequently, the group provided a roadmap for the return of these barrels. For the first couple months of this oil production recovery, OPEC+ was careful that the oil market remained in deficit. As a result, oil inventories kept falling until they reached their 5-year average in mid-summer 2021 (se Exhibit 8).

Exhibit 8: Global petroleum stocks were back to 5-year averages by mid-summer 2021

Kb, levels vs 5-year average

Source: Goldmoney Research

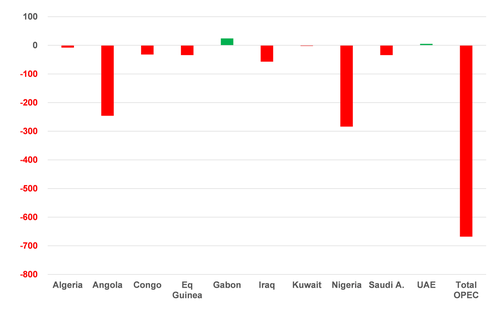

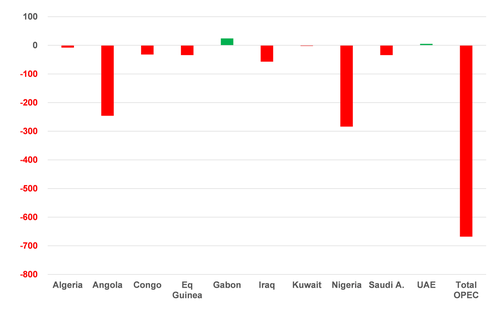

However, actual OPEC+ production is lagging the quotas for many months now, and the gap between actual and target becomes increasingly wider. The reason is that some of the smaller OPEC members struggle to produce as much as they would be allowed under the plan (see exhibit 9). These are not voluntary cuts. It has become obvious that the capacity of many OPEC members simply isn’t there as these countries are plagued with domestic issues that prevent full production. On top of that, the non-OPEC members of OPEC+ are also producing about 200kb/d below their quotas, and that was before the war in Ukraine reduced Russian exports.

Exhibit 9: Many OPEC members keep producing below their quotas

Kb/d

Source: OPEC

Interestingly, the core OPEC members Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Kuwait are for once not stepping in to fill the gap. In our view, this may be partially politically driven due to some tensions between the US and some OPEC members, but more likely it is also due to their own capacity constraints. In April 2020, Saudi Arabia briefly ramped up production to 12mb/d as the Kingdom reacted to Russia’s’ refusal to commit to a production cut (see Exhibit 10). This strategy backfired as it meant raising output right into the largest demand crash in history. However, it does give some insights to what Saudis production capacity is. We think Saudi Arabia went beyond their sustainable production capacity at that time. It is unlikely that they could sustain this output level for an extended period. Their production capacity for the medium term is likely closer to 11-11.5mb/d. Any capacity increase would require substantial investments in our view, and it would take years to achieve.

Exhibit 10: Saudi Arabia demonstrated that they can push production to 12mb/d over a very brief period, but sustainable production capacity is likely significantly lower

Source: Goldmoney Research, OPEC

While Saudi Arabia is still producing below their sustainable capacity, the country can’t really step in and fill the production gaps left by the less stable OPEC producers, as it would mean it could not increase production anymore when it is supposed to according to the OPEC+ roadmap. The country has no choice but to stick to their own predetermined production path. The same is true for other core-OPEC members. As a result, demand continued to exceed production in 1Q22 at a time when in theory, we should have already shifted to an oversupply in the first two months of the year.

This has pushed global inventories lower and lower. As we have explained in earlier reports, there is a very strong relationship between the level of inventories and crude oil time-spreads, the difference between the prompt prices and longer-dated prices on the forward curve (see Exhibit 11). In a nutshell, when inventories are low, consumers of a commodity – in this case petroleum products – are willing to pay a premium for immediate delivery. It is preferable to pay this premium than to face the risk of having to shut down the business because they run out of oil (jet fuel, diesel etc.). In such a situation, prompt prices trade over future prices which is called “backwardation”. When inventories are high, consumers have no preference for immediate delivery. Instead, storage, insurance, and financing costs mean that consumers rather not sit on inventories, but would prefer delivery in the future. In that situation, prompt prices will trade below forward prices and the curve is in “contango”.

Exhibit 11: Crude oil time-spreads are inversely correlated to inventories

% time-spread 1-60 months, prediction based on inventory levels

Source: Goldmoney Research

The extent to which a forward curve is in backwardation or contango is strongly correlated to the level scarcity or abundance of inventories relative to demand. At the moment, we see an extreme level of backwardation in the front of the curve. The market signals extreme scarcity of oil stocks and the risk of further supply shortages. This is the result of the persisting undersupply discussed above that led to a situation of very low inventories, but also due to concerns over potentially even larger shortages due to missing Russian crude oil supplies.

To what extent the Ukraine conflict has exacerbated this issue from a fundamental perspective is difficult to assess at the moment. So far the US is the only nation that has outright banned imports of Russian oil and products. While this might create challenges for some refiners that rely on specific grades of imported Russian crude, it doesn’t alter the global supply and demand picture. US refiners will be forced to switch to an alternative grade but the Russian crude that used to go to the US (only about 670kb/d in 2021, of which 200kb/d was crude and the rest products, mostly fuel oil and VGO that was used in the US refinery system) will find its way to Asia (see Exhibit 12).

Exhibit 12: US import volumes of Russian petroleum are relatively small

Kb/d

Source: Goldmoney Research, EIA

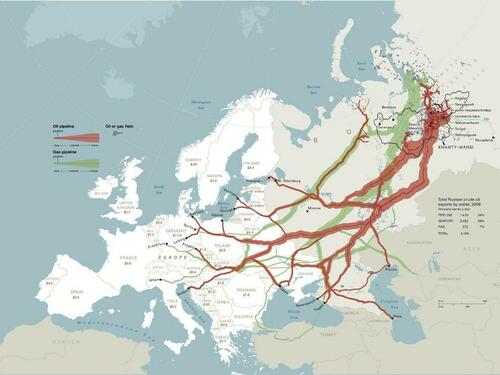

The EU has imposed some sanctions on Russia that impact the commodity sector overall, but it has so far refrained from banning energy imports. However, over the past weeks it has become apparent that the voluntary sanctioning by Western companies – sometimes as a result of public outcries – is having an impact on Russia ability to export crude to the West regardless. There have been several reports that international commodity trading giants were forced to offer Urals (a Russian crude oil grade) at discounts of up to $30/bbl as they could not find a willing buyer. Russian crude exports are dependent on pipeline flows to Europe. These flows can’t be entirely substituted by seaborne exports at the moment. Hence the reluctance of Western oil firms, merchants, banks, shippers, seaports, and insurance companies to refrain to deal with Russian entities or outright stop dealing with anything that could be related to Russia can still lead to substantial reduction of Russian exports even as there is no legal ban. At the moment this probably affects around 1mb/d of Russian crude supplies. On top of that, Russia just announced that the CPC pipeline – a Kazakh-Russian Caspian Pipeline Consortium – is undergoing unplanned maintenance of up to two months, reducing global supplies by a further 0.5mb/d.

Exhibit 13: Russian oil and gas exports are dependent on pipeline flows to Europe

Source: National Geographic https://www.nationalgeographic.org/photo/europe-map/

On the flip side, IEA member states agreed to release 60mb of petroleum from their strategic reserves to alleviate the current shortages. Most of it will come from the US, and 29 other countries have committed to smaller volumes. However, that covers the current losses from Russia by just one to two months. The US had already orchestrated a coordinated SPR release last November to deal with high prices prior to the Ukraine war. The reaction was a short sell-off and an immediate recovery with prices pushing much higher.

There is no easy way to predict how this picture changes over the coming months.

-

It’s certainly key how the Ukrainian conflict progresses. On one hand, Europe is unlikely to ban oil and gas imports unless the conflict escalates in a dramatic way. On the other hand, while European sanctions are unlikely to be eased in the short term even if Ukraine and Russia come to some sort of agreement, such a scenario would likely ease the pressure on Western firms to maintain their voluntary sanctions.

-

Core-OPEC members do have spare capacity, and they will bring it back as planned and not faster. But they run out of spare capacity in 2H2022.

-

US production is also growing again, but not unlike OPEC, the shale oil producers made clear that they are also sticking to their production targets and are undeterred by higher prices, Non-OPEC (non-shale) production is growing as well, but it is recovering from the declines over the past 2 years rather than incrementally growing. This means it’s a one off and most of the increase have already happened.

-

Finally, there is a significant chance that the Iranian nuclear deal will be reactivated, allowing for about 1 million b/d of crude production to come back online relatively quickly.

-

This uncertain supply picture is facing a rapid improvement in global demand on the back of what seems to be the rapid abandonment of Covid19 mandates worldwide, which would allow air travel to rebound strongly over the coming months.

We think the near-term risks are skewed to the upside as demand keeps exceeding supply despite the OPEC ramp up, and Russia supply issues only exacerbate this situation. This would lead to even stronger backwardation until prices start to impact demand enough to balance the market. The current conditions in the oil market are critical and we could see real oil shortages by this summer if the disruptions to Russian oil supplies persist or even worsen.

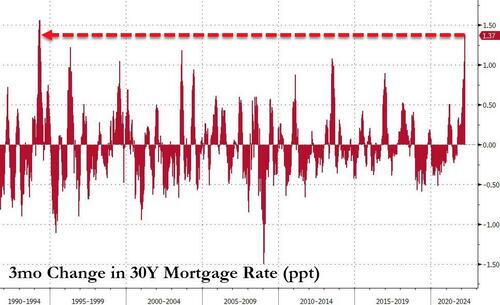

So it appears that the strong crude oil prices are mainly the result of a very backwardated curve because supply is struggling over the short term. While this adds to the overall inflation pressure coming from generally higher commodity prices, breakeven inflation expectations suggest that the market is expecting these pressures to remain only over the near term. In other words, the market thinks the supply issues will be transitory. However, we think an even bigger and more permanent issue has been brewing in oil markets for years and it is finally filtering through to the back end of the forward curve. Longer dated prices have broken out of their 5-year range and have been moving up relentlessly. We think the oil markets have finally begun to understand that a lack of investments in large oil projects over the past years is threatening supply over the entire next decade, at a time when demand will still be growing as the electrification of the transportation sector will not impact demand meaningfully for years to come. The sharp upward moves in oil prices amidst a broader commodity prices rally have pushed realized inflation and near-term (0-2y) inflation expectations up strongly. But inflation expectations beyond that time horizon have proven to be resilient.

So far the back end of the oil curve moved up only $15/bbl. However, we think that once back end prices are moving in a similar fashion to what we are currently witnessing in the front, longer term inflation expectations will likely begin to move up too.

We will do a deep dive into the strong move at the back end of the oil curve in an upcoming report