Documents uncovered in a civil rights lawsuit show Florida prison officials and medical staff allowed an incarcerated man’s prostate cancer to spread untreated until he was left paralyzed, terminally ill, and afflicted with infected bed sores that rotted to the bone.

When he wrote desperate pleas for help, one official concluded, “This is not an emergency.”

In a federal civil rights lawsuit filed last year, former Florida inmate Elmer Williams alleges that corrections officers and nursing staff denied and delayed medical treatment for months after he filed a grievance against them. The complaint argues these delays were not just bureaucratic incompetence but retaliation “intended and designed to prevent [Williams] from receiving a timely diagnosis.” The lawsuit alleges violations of the Eighth Amendment and the Americans with Disabilities Act; it names several Florida Department of Corrections (FDC) officials and medical staff employed by Centurion, a private health care provider that contracts with the FDC.

Williams, 56, spoke to Reason from the hospital bed where he has spent most of his time since the FDC granted him medical release last October, and where he will in all likelihood spend his final days.

“Slowly, slowly, slowly, they just let me fall apart,” he says.

Many of Williams’ claims are corroborated by medical records that reveal staff were aware of his extremely high indicators for prostate cancer, aware of a long-overdue “urgent” referral to a urologist, and aware of his rapidly deteriorating condition. Photos accompanying Williams’ suit show deep bed sores on his buttocks and ankles—evidence of atrocious neglect. He has yet to recover from those wounds nearly a year after his release from prison.

The case of Elmer Williams is only an extreme example of medical neglect that is common, not just in Florida prisons but in lockups across the country. The Constitution guarantees incarcerated people the right to basic medical care and hygiene, but indifference, staff shortages, cost-cutting, and the high bar to prove an Eighth Amendment violation have turned its ban on cruel and unusual punishment into a broken promise. Reason has previously reported on how federal prison officials let a man with treatable cancer waste away while lying to a judge about his treatment; how a woman died in federal prison after suffering in pain for eight months while waiting for a routine CT scan; and how prisoners in Arizona died excruciatingly painful deaths while unqualified, overworked nursing staff did nothing.

“The Constitution requires Florida prisons to provide adequate medical care to its prisoners and prohibits them from deliberately delaying treatment for serious medical needs,” James Slater, one of Williams’ attorneys, says. “Upon arriving at Suwannee Correctional Institution, Elmer Williams presented serious documented medical needs which rapidly worsened. Instead of providing him the treatment the prison knew he needed, prison officials and medical staff forced him to go months without the appropriate treatment resulting in his condition predictably becoming terminal.”

Centurion did not respond to a request for comment. An FDC spokesperson declined to comment on Williams’ case, citing the department’s policy of not commenting on pending litigation.

Williams was serving a 40-year state prison sentence for burglary when he was transferred to Suwannee Correctional Institution in November of 2021.

He had previously been treated for prostate cancer, which was in remission. However, medical intake records obtained by Williams’ lawyers show that a month prior to his transfer to Suwannee he had an urgent referral to a urologist. The level of prostate-specific antigens (PSA) in his blood—an indicator of potential prostate cancer—had recently spiked.

Around the same time he transferred to Suwannee, Williams also started losing his balance and falling. He began complaining of severe back pain and numbness in his legs. On November 18, 2021, he fell out of his bunk and tried to declare a medical emergency. However, Williams claims that both a correctional officer and a nurse refused to provide him with a wheelchair.

Several days later, Williams was thrown in a disciplinary confinement cell for failing to show up for a job assignment, which he couldn’t do without a wheelchair. The lawsuit alleges this was retaliation for Williams’ writing a grievance against the nurse and correctional officer.

“It was only many months later that Plaintiff was assigned his own wheelchair, despite the obvious and apparent need for one demonstrated over the next several months as Plaintiff became completely paralyzed from the chest down,” the lawsuit says.

In the meantime, he was left alone for 30 days in a confinement cell, where he says he had to drag himself across the floor to get food or use the toilet while correctional officers mocked him.

“I’m stink [sic] more than ever now because my cell floor is pissy from me peeing on it all day when I don’t have the strength to make it to the toilet,” Williams wrote on December 2, 2021, in a sworn affidavit. “Haven’t been given a shower in nine days because I’ve gone paralyzed from the delayed medical treatment.”

That same day, Williams filed a grievance, complaining, “Now my life and health is in jeopardy because I’m being denied a wheelchair when I can’t walk, so I can’t get my bloodwork done to determine where my PSA level is at and what’s wrong with me.”

Williams was released from confinement later that month, and his health continued to decline. Medical records show that Williams saw the prison doctor again on December 20, 2021, complaining that he could not walk or even stand. Despite that, the doctor wrote in her notes, “I do not recommend a wheelchair at this time.” The doctor also noted that she would “continue monitoring prostate issues,” although she was neither a urologist nor an oncologist.

Williams was admitted to the prison infirmary on January 7, 2022, with swelling of both his legs, irregular pulse, decreased mobility, and infected pressure ulcers, also known as bed sores, on his heels. From the infirmary, he began firing off a series of grievances regarding his treatment and his rapidly deteriorating health.

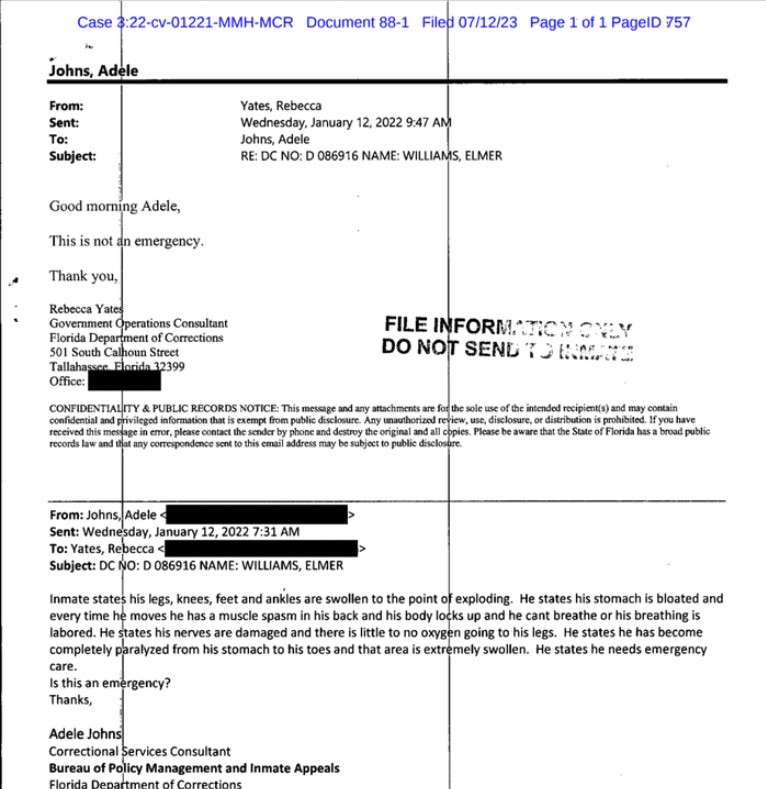

On January 12, 2022, an FDC staffer handling one of Williams’ grievances emailed Rebecca Yates, an FDC government operations consultant, and described Williams’ litany of symptoms:

“Inmate states his legs, knees, feet and ankles are swollen to the point of exploding. He states his stomach is bloated and every time he moves he has a muscle spasm in his back and his body locks up and he can’t breathe or his breathing is labored,” the staffer wrote. “He states his nerves are damaged and there is little to no oxygen going to his legs. He states he has become completely paralyzed from his stomach to his toes and that area is extremely swollen. He states he needs emergency care.”

“Is this an emergency?” the staffer asked Yates.

“This is not an emergency,” Yates replied roughly two hours later.

It may not have been an emergency for the FDC, but Williams felt his life slipping away with every minute of delay.

“Every day this cancer is living inside my body without treatment is another day my organs are deteriorating,” Williams pleaded in a January appeal directly to the head of the FDC after one of his grievances was denied, “and who knows at what rate??”

His grievances were all rejected.

In February 2022, despite his festering wounds and encroaching paralysis, Williams was discharged from the prison infirmary and back into the general population. His lawsuit claims he was still not assigned a permanent wheelchair. Williams says he had to pay other inmates to take him to the shower, help him get his diapers on or off, and take him to breakfast.

If no one was available or willing, he went without. When he did make it to the shower, he said he had to sit on the unsanitary floor.

“I just felt humiliated, degraded,” Williams recalled in a deposition for his lawsuit. “Psychologically, I wanted to—I wanted to really like, you know, like hurt myself because that’s really a low, that’s a low in prison to be exposing in front of 70 some guys walking by you while you just there wiping your butt. And they wouldn’t give me no diapers or nothing. I was soiling my clothes and my pants.”

Sitting on the shower floor was even worse for Williams because he had developed large, infected bed sores on his buttocks during his stay in the infirmary. As his lawsuit describes it, the sores flourished into “deep necrotizing wounds on his buttocks that went all the way to his pelvis bone.”

Williams said he didn’t even realize the extent of the wounds until later. “One day I just so happened to take a mirror and look back there, and I panicked,” he said in the deposition. “I screamed. I screamed. The guards came. I’m like, ‘What the hell is this? What happened?’ And nobody could tell me what happened.”

This is far from the first time the FDC has faced accusations of refusing to accommodate the most basic needs of inmates with disabilities. In 2017, the FDC settled a lawsuit by the advocacy group Disability Rights Florida by agreeing to provide accommodations, including wheelchairs, to incarcerated people with disabilities. In 2021, it settled another lawsuit by Disability Rights Florida accusing it of breaching the previous settlement. Williams’ lawyers are currently representing another disabled Suwannee inmate who claims staff refuse to give him enough adult diapers.

The FDC and Centurion argue in motions to dismiss Williams’ suit that medical logs actually show that he was given continual, attentive care, including antibiotics, dressings for his wounds, and—eventually—an appointment with a urologist.

Williams saw a urologist in March 2022, roughly five months after his “urgent” referral. His PSA level had risen from 5.2, when he first arrived at Suwannee, to 43. The baseline PSA level for potentially active prostate cancer is 4.

In June 2022, Williams saw an oncologist, but by that time, all doctors could offer him was palliative care. The cancer had spread to his hips, spinal cord, and lymph nodes. The lawsuit claims Williams was not informed of his terminal condition until he was transferred to a state prison hospital in August.

Williams would have died behind bars, but the Florida Justice Institute (FJI), a criminal justice advocacy group, came across his case and decided he would be a good candidate for compassionate release—a Florida policy that allows some terminally ill inmates the mercy of dying at home.

“We had been looking into this issue as a way to highlight not only Florida’s aging prison population, but we also represent a lot of people both in larger cases and smaller cases with disabilities,” Dante Trevisani, executive director of FJI, says.

Williams had previously filed a petition for medical release, which was rejected. FJI refiled the petition on Williams’ behalf. He was released from FDC custody in October of last year.

At a real hospital, doctors gave Williams six months to live. He has outlived his prognosis, but he struggles to cope with the diminished quality of life he’s been left with. Since arriving at the hospital, he’s spent all but 15 minutes lying in the same bed, in the same room.

“I’m hanging in there, but it’s very, very hard. Getting used to living this type of life is very difficult mentally,” Williams says. “From the pain all the time, and because I only get a visit maybe two times, three times a week, so I’m left here on my back, just suffering, day by day.”

The post 'This Is Not an Emergency' appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest https://ift.tt/IDaQnkz

via IFTTT