Ron Berman agonizes over how to tell this story, where even to start, because the short version doesn’t capture the full travesty and the long version is overwhelming. But here’s the crux of it: A group of federal prison guards raped his daughter and got away with it. Not only did they get away with it, but they got away with it even after they admitted they did it.

Berman’s daughter, Carleane, was one of at least a dozen women who were abused by corrupt correctional officers at FCC Coleman, a federal prison complex in Florida. In December, a Senate investigation revealed that those correctional officers had admitted in sworn interviews with internal affairs investigators that they had repeatedly raped women under their control.

Yet thanks to a little known Supreme Court precedent and a culture of corrupt self-protection inside the prison system, none of those guards were ever prosecuted—precisely because of the manner in which they confessed.

Most of the guards retired before they could be fired, meaning they walked with their retirement benefits intact. Over the last five years, Berman’s daughter and the rest of those women were failed by nearly everyone around them at every level of government.

Berman has been emailing and calling everyone he can think of—his congressional representatives, the FBI, federal prosecutors, local prosecutors, the county sheriff, reporters—trying to get justice for his daughter.

“It’s not the system that failed her,” he says. “It’s the people.”

‘Don’t Say Anything, Don’t Ask Questions’

Three years ago, Reason reported on a federal lawsuit filed by women abused at Coleman. The lawsuit claimed that prison leadership created a “sanctuary” for a cadre of serial rapists employed by the U.S. government.”

The sexual abuse at these female prisons is rampant but goes largely unchecked as a result of cultural tolerance, orchestrated cover-ups and organizational reprisals of inmates who dare to complain or report sexual abuse,” the suit said.

Berman’s daughter was one of the plaintiffs in that suit. Carleane Berman arrived at Coleman’s minimum security work camp for women in March 2017 to serve a 30-month sentence for her role in a Miami crime ring that imported huge amounts of the club drug molly, or MDMA, from China.

She had started using drugs as a teenager. Despite increasingly severe interventions from her parents, it just got worse. She ran away for days at a time, getting lost in Miami Beach’s all-night clubs. “I was caught up in the typical nightlife scene that fueled my addiction,” she would later tell the Miami Herald.

That was how she met Jorge Hernandez, a charismatic, tattooed military veteran who recruited several young women, including Berman, to wire money and pick up packages of molly. Everyone got busted after an irate girlfriend ratted out Hernandez’s business partner to the police.

Berman’s sentence didn’t look so bad on paper. As federal prison goes, two and a half years at a minimum security camp is about as good as it gets. You live in dormitory-style housing; you have access to jobs and programs; your movement isn’t as restricted; there’s plenty of fresh air.

At Coleman, Berman was on the landscaping crew, where she worked with Miranda Williams, who also arrived at Coleman that year. The two quickly became the sort of ride-or-die friends you only make when you’re thrown together in bad circumstances.

Williams says Berman was a fun, bubbly person, a bit wild, quick to help others without expecting anything in return. She used to take the four-wheelers they used for landscaping and run them through mud puddles when it was raining.

Before long, Williams and Berman started hearing rumors.”

Inmates would basically warn me that if I see anything, hear anything, something happens with me, then not to speak, don’t tell, don’t say anything, don’t ask questions, because I’m gonna end up in a worse situation than what I was already in,” Williams says. “And at the time I didn’t know what that meant, so I just kept my mouth closed.”

Williams says she was first raped by a correctional officer in mid-June 2017. It started with one officer, but then there was another, and then another.

“The harassment quickly evolved into sexual assault as Officers [Christopher] Palomares, [Keith] Vann and [Timothy] Phillips coerced, intimated and demanded that Ms. Berman engage in all types of sexual activities with each of them including oral sex, intercourse, and group sex with Ms. Flowers,” their eventual lawsuit said. (Williams’ last name was formerly Flowers.)

“It happened as frequently as they wanted it to,” Williams says.

As far as the Justice Department and federal law are concerned, there is no such thing as consensual sex between a correctional officer and an incarcerated person. It is sexual assault—always.

Congress passed the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) in 2003. It was supposed to create zero-tolerance policies for sexual abuse in U.S. prisons and jails. PREA is mostly toothless, though—and in the federal prison system, festering corruption made it a bad joke. In December 2022, the former warden of a federal women’s prison in California was convicted of sexually abusing incarcerated women. He was also the prison’s PREA compliance officer.

“I was incarcerated for almost eight years, and I saw it at pretty much every single institution I was at,” Kara Guggino, a former Coleman inmate and a plaintiff in the eventual lawsuit, told Reason in 2019. “I was at maybe six different places, and this was going on everywhere. But it was by far the worst at Coleman.”

‘Multiple Admitted Sexual Abusers Were Not Criminally Prosecuted’

When Berman first reached out to Reason, the lawsuit was over and the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) had stonewalled every attempt to uncover more information about how these guards had been allowed to run rampant for years.

The Miami Herald tried requesting personnel files on all of the named officers to see if they had a history of complaints and misconduct. “The Bureau of Prisons responded that absent an ‘overriding public interest,’ it would not provide such documents, calling the provision of such records ‘an unwarranted invasion of their personal privacy,'” the newspaper reported.

Berman filed a records request for internal affairs interviews with the correctional officers, but was likewise denied.

Reason filed a records request for the interviews, internal affairs memos, and emails between some of the correctional officers named in the lawsuit. The BOP rejected all those requests.

What really happened at Coleman might have been obscured forever, but there was one group the BOP couldn’t ignore: Congress.

Last December, the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (PSI) released the results of a 10-month investigation into sexual abuse of incarcerated women in the federal prison system.

The report found that the Bureau of Prisons has failed to implement PREA and that long delays in investigating complaints created a backlog of more than 8,000 internal affairs cases. The report concluded that these failures “allowed serious, repeated sexual abuse in at least four facilities to go undetected,” including Coleman.

“BOP’s internal affairs practices have failed to hold employees accountable, and multiple admitted sexual abusers were not criminally prosecuted as a result,” the report said.

Overall, the investigation found that BOP employees sexually abused female inmates in at least two-thirds of federal women’s prisons over the last decade.

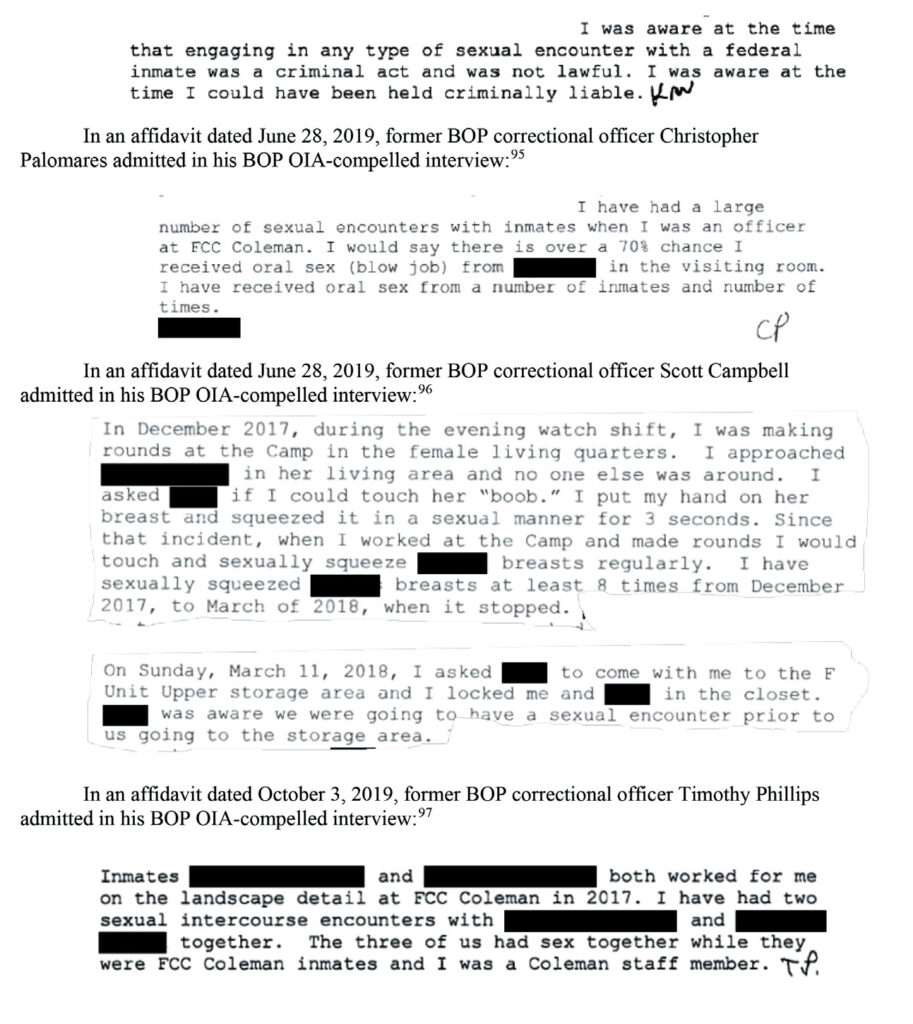

Senate investigators also obtained what Berman, the Miami Herald, and Reason could never get our hands on: “copies of non-public sworn, compelled statements from officers at FCC Coleman, wherein the officers admitted to sexual abuse of female detainees in graphic detail.”

‘Oh My God, This Piece of Shit Is Talking About Me’

Judi Aloe, a former Coleman inmate, was skimming the PSI report when she noticed a familiar name: Campbell.

In a portion of one of those sworn affidavits reprinted in the report, a former BOP correctional officer named Scott Campbell admitted to repeatedly assaulting a woman, whose name was redacted:

Aloe knew who the woman was, though.

“Oh my God,” she thought. “This piece of shit is talking about me.”

Aloe arrived at Coleman in 2016. She was intent on keeping her head down and getting through her four-year sentence for her role in an odometer tampering scheme as quietly as possible. She didn’t have visitors. She didn’t make phone calls. She was mostly invisible. She says she was assaulted not only by Campbell but also by Palomares, who snuck into her room and groped her.*

“I actually had my headphones on, and I don’t know if I was doing a word search or if I was drawing,” Aloe recalls. “All of a sudden [Palomares’] hand came over my mouth and the other hand was groping my breast. He took his hand off my breast and put it up to his mouth. Like, shhhh.”

The abuse escalated over the next several months until Campbell raped her in a supply closet. Aloe wants the officers prosecuted.

“Do the math,” she says. “If I was a victim of domestic violence, and I did four years in prison for odometer tampering, what do they get for being sex traffickers and serial rapists?”

Queen for a Day

How can a federal law enforcement officer admit to a crime in a sworn interview and not be prosecuted? That’s the question that rankles Berman, Aloe, and most everyone else who comes across this case. The answer involves bureaucratic dysfunction and a 50-year-old Supreme Court decision.

The Justice Department Office of Inspector General (OIG) has what it calls “right of first refusal” to investigate misconduct in Justice Department components, such as the FBI and BOP. According to a 2021 letter the BOP sent to Florida Republican Sen. Marco Rubio in response to inquiries from Rubio’s office about the scandal, the BOP Office of Internal Affairs (OIA) referred allegations that guards raped Carleane Berman to the OIG three times—in September 2017, November 2017, and May 2019. Each time, the OIG deferred launching a criminal investigation, leaving Internal Affairs to handle it as an administrative matter.

Internal Affairs then forced the correctional officers to sit for sworn interviews. Once those officers confessed to sexual assault, the possibility of criminal prosecution evaporated. The Supreme Court ruled in a 1967 case, Garrity v. New Jersey, that when a government employee is compelled to answer questions under oath as a condition of employment, it would violate the Fifth Amendment’s protection against self-incrimination for prosecutors to use those statements.

By compelling prison guards to admit to criminal conduct, BOP internal affairs investigators got enough dirt to kick them out of the agency but also shielded them from future criminal prosecution.

Although it would technically be possible for federal prosecutors to bring charges now, they would have to rely on other evidence and prove that nothing in their case was tainted by those interviews. Perversely, the more detailed and thorough the confession, the harder it is to prosecute—a feature that any BOP employee who screws up badly enough to get called in for a sworn interview understands.

“There is no world in which we can say this is a good outcome,” the Justice Department Inspector General testified before the PSI. “These individuals knew they have been compelled and could retire and resign and spill to [BOP] OIA and basically have immunity in some cases for engaging in sexual activity with multiple inmates. It is a terrible outcome.”

The PSI report refers to these sworn interviews as Garrity interviews, but that’s not what they were known as at Coleman.

Rob Farlow, a former correctional officer at Coleman, says they were called “queen for a day.” As in, “Did you hear that Smith got queen for a day?” The term is more commonly used in criminal law to refer to a proffer agreement between federal prosecutors and a potential defendant—basically, spill the beans in exchange for possible immunity—but it worked much the same way between BOP internal affairs investigators and correctional officers.

Garrity interviews also allowed the BOP to quietly remove problem officers without the media attention that criminal charges would bring. “It’s their way of covering up embarrassment for the Bureau,” Farlow says.

‘I Knew They Were Scumbags’

By the time Carleane Berman and Miranda Williams arrived at the Coleman women’s camp in 2018, the abuse had been going on for years, says Ann Ursiny, another former Coleman inmate. She had been at Coleman since 2012, serving a 10-year sentence, and was an old hand around the camp. She knew how things worked and when to keep her mouth shut.

Ursiny also knew there was at least one person at Coleman trying to do something about it: David DeCamilla, a BOP special investigative supervisor (SIS). An SIS acts like a detective inside a federal prison, investigating potential misconduct and criminal activity.

DeCamilla had been nagging Ursiny to talk to him about what was going on at the camp. He took his job seriously. But no one else took his job seriously—not the inmates like Ursiny, who refused to talk to him, and not the prison administration, which was content to let him spin his wheels while the problem officers had unfettered access to their victims.

“Oh my God, he chased me around that whole complex on my tractor for years,” Ursiny says. “And every time he talked to me I lied, because I had seen so many of my peers be whisked away to county and transferred. I was like, yeah, that’s not happening to me.”

To understand why it took the incarcerated women at Coleman so long to come forward, and why many even initially denied to investigators that any abuse had occurred, you have to understand how much leverage the correctional officers had over them.

There are innumerable small ways a correctional officer can make life difficult for an inmate. At the pettiest level, getting on the wrong side of an officer could lead to losing a desirable work assignment. Maybe your stuff starts getting tossed during “random” searches, or your requests to see a nurse get ignored. You get write-ups for ticky-tacky disciplinary infractions.

The Coleman women also all say it was well-known that if you reported a correctional officer for misconduct, you would be transferred to another federal prison, worse than Coleman and hundreds of miles from your family. If you weren’t sent to another federal prison, there was another possible destination. When Coleman women had to be held in higher security housing, either because of a disciplinary infraction or for their own safety—or at least that was the justification—they could be sent to the nearby Sumter County Detention Center.

A county jail might sound like an upgrade from a federal lockup, but it was the opposite. None of their possessions and none of their commissary funds transferred with them, stranding them without any money. They couldn’t participate in programs that shaved time off their sentences. They also disappeared from the BOP website, since they were technically not in BOP custody, leaving their families with no idea where they were.

The Sumter County Sheriff’s Office did not respond to a request for comment.

There were less official ways to keep women quiet, too. Correctional officers read their emails and monitored their phone calls.

“The officers would look up my [pre-sentencing information] report, and they would track where my husband was going, which facilities he was being transferred to,” Williams says. “They knew my kids’ names, my parents’ names. They knew where everybody lived. They threatened to use that information and tell various stories about me and what I’m doing in there, trying to hurt my reputation, trying to destroy my marriage, trying to hurt my chances of seeing my kids again when I got out.”

Ursiny says an officer once pulled up her family’s home on a computer and said, “Isn’t this your daughter’s house? Doesn’t she have a couple of kids? So just make sure when the investigators talk to you, say the right thing.”

As a result of all this, the guards at the Coleman camp ruled it as a little fiefdom. They controlled the cameras, they knew where the blind spots were, and they could dole out favors in the form of contraband. “They were definitely bringing in drugs,” Aloe says. “They were bringing in alcohol. I know they were bringing in G-strings and stuff.”

Rob Farlow was a Bureau of Prisons officer for eight years, seven of them at Coleman. He worked with the officers named in the lawsuit and PSI report. “I knew they were scumbags,” he tells Reason.

The rumors and red flags were hard to ignore, he says. Bureau of Prisons correctional officers bid on posts and shifts every three months, which are then doled out based on seniority, but Farlow noticed the officers at the women’s camp never seemed to request different posts or move, even after Farlow heard that investigators were starting to ask questions about them.

“I’m just thinking, Jesus, it’s been one year, two years, three years,” Farlow says. “Here we are, these guys are still there, and they’re still working in the same spot.”

The turning point for Ursiny came one day in 2016, when investigators came to ask her about allegations another woman had made about sexual misconduct by staff. She lied, like she always did. No one else would substantiate the woman’s story either, and the next day she was gone, transferred out.

It started to eat at Ursiny, though—the way that woman was treated and the way she was talked about.

“She was ridiculed and just spoken of so harshly by the officers and the inmates,” Ursiny remembers. “And after a while, you know, I have a conscience and I’m a mom. My God, if my daughter had gone through something like this—how can you just sit back and not say anything? How can you just allow that to happen?”

At the urging of other friends in Coleman, Ursiny finally went to prison staffers, including DeCamilla, to tell what she knew. DeCamilla initially tried to get her to wear a wire to catch the officers, but superiors shot down that plan, so he settled for asking her for a list of women she knew had been assaulted by staff.

Ursiny had been at Coleman for many years at that point, and a lot of women had passed through. She says that when she finished the list and handed it to DeCamilla, it had more than 100 names on it.

‘Like a Fly Trying To Move a Wall’

Other women were coming forward independently of Ursiny, too. As the allegations against Coleman officers accumulated, Carleane Berman and Miranda Williams were both sent to the Sumter County jail in late 2017 while BOP investigators tried to get them to talk.

Jail records show Berman was held in the county jail for three months. Williams ended up spending five months there, until her federal sentence was completed.

“It was maximum security, so we didn’t ever go outside,” Williams says. “It was one big room with, I think, a total of 24 women, four toilets, one shower, no warm water even.”

Online jail logs show that five plaintiffs in the eventual Coleman lawsuit were housed at some point in the Sumter County jail. They are all listed as “courtesy holds.” At least two of the future plaintiffs were in the jail when PREA auditors arrived for their 2018 inspection of Coleman to ensure the prison complex was in compliance with the anti-rape law.

The auditor noted without concern that “many of the offenders who reported abuse over the applicable audit period were no longer housed at the FCC.” The auditor appears to have been unaware that Coleman prisoners were being held in the Sumter County jail. “There were no inmates involuntarily segregated due to high risk of victimization,” the auditor wrote. Coleman passed its PREA audit.

But the internal affairs investigation was coming to a different conclusion. One by one over the course of 2018 and 2019, correctional officers were brought in for compelled interviews. Five confessed to sexually assaulting multiple female inmates.

“I have had a large number of sexual encounters with inmates while I was an officer at FCC Coleman,” Christopher Palomares admitted in an interview with Internal Affairs. “I would say there is over a 70 percent chance I received oral sex (blow job) from [REDACTED] in the visiting room. I have received oral sex from a number of inmates a number of times.”

DeCamilla wrote an email on May 21, 2019, to the federal prosecutor who put Ursiny in prison, in an attempt to get her an early release for her help:

“Sir, I am an investigator with the BOP at FCC Coleman Medium. Inmate Ursiny has been providing me with information pertaining to staff misconduct. Specifically, she alleged she was inappropriately touched by 2 staff members at Coleman. Inmate Ursiny was one of many other inmates who made the allegations about these two staff members sexually abusing them over the years. During the interview with one of the staff members, he admitted in his affidavit to sexually abusing 6 inmates at the female camp. Ursiny was one of those victims. The staff member was covered under a Form B at the time. This staff member identified by Ursiny and other inmates as sexually abusing them resigned 1 hour before he was to be interviewed. Ursiny is not looking for anything in return for the information she has provided, she is projected to be released on April 24, 2021. I just wanted to make you aware of her cooperation in assisting me in getting rid of two corrupt staff members at FCC Coleman. Thank you.”

But the same institutional pressure that kept inmates quiet kept honest guards quiet, too. If you made too much of a stink, Farlow says, the system would turn on you. He described DeCamilla’s efforts as “like a fly trying to move a wall.”

According to the lawsuit filed later by the women, DeCamilla was demoted and subsequently retired. “There’s only so much he could do without them putting the bull’s-eye on his back,” Farlow says.

Farlow believes President Joe Biden should pardon the victims and clear their records. “It’s a disgrace what happened to them,” he says. “They were sent to federal prison to do time, a certain amount of years. They weren’t sentenced to rape.”

‘Homewreckers, Thirsty Bitches, and Whores’

When the investigation of the Coleman officers concluded in 2019 after nearly three years without any criminal charges, the women moved on to other remedies. One of them had a family member who was a lawyer, and they began a series of meetings and furtive phone calls to start piecing together the claims for a lawsuit.

According to that lawsuit, there were unexplained delays whenever lawyers arrived at the prison for scheduled interviews with inmates. Ursiny says Coleman staff refused to leave the room during phone calls with lawyers.

Nevertheless, the lawsuit was filed in December 2019. It was notable not just for the allegations but for the number of plaintiffs and the fact that they had all gone on the record with their real names, some of them while still behind bars.

For those that were incarcerated at Coleman, Ursiny says retaliation started as soon as the lawsuit hit the docket. Ursiny says officers started calling the women who joined the suit “homewreckers,” “thirsty bitches,” and “whores.” She remembers one night a guard flipped on the lights in the dormitory and started screaming obscenities at them.

But once the lawsuit was filed, the rotten mess was out in the open. In a July 2020 response to the lawsuit, the U.S. government confirmed that five of the correctional officers accused of sexual assault had admitted in sworn interviews to the conduct. One of the plaintiffs told the Tampa Bay Times that she was raped punctually every Wednesday for six months.

The government still fought the Coleman women’s claims even then, though. In a confidential open settlement memorandum—destroyed at the conclusion of the lawsuit, but a copy was obtained by Reason—the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Middle District of Florida argued that the actions of former correctional officers were outside the scope of their employment, even if they were in uniform when they committed them; therefore, it claimed, the U.S. government couldn’t be held liable for their conduct.

The memo also argued that some of the plaintiffs’ claims, including Berman’s and Williams’, were barred by a two-year statute of limitations, and that their fears of retaliation didn’t meet the “extraordinary circumstances” necessary to disregard the deadline. The memo went so far as to question their diligence in avoiding being raped: “There does not appear to be any evidence that Plaintiffs made any effort to seek protection from those former correctional officers through any of the mechanisms in place at BOP facilities or even after they were released.”

Nevertheless, the U.S. Attorney’s Office preferred to settle the case quickly and cheaply. Williams laughs when she remembers their initial play.

“The first offer that I received was $10,000, and [the magistrate judge] was like, ‘That’s a lot of money. You need to take that money and settle and move on with your life,'” she remembers. “Both me and Carly were like: No. First of all, it’s not even about the money. It’s about the principle of what happened and the fact that you guys aren’t even doing anything.”

All of the women Reason spoke with said the magistrate judge overseeing mediation of their lawsuit pressured them into settling.

“She told us you better take this, because if you don’t, it’s going to draw out,” Ursiny says. “She just painted the bleakest picture that you could ever paint. And my response to that was that I don’t really care because as far as I’m concerned, if I get anything, it’s found money, and it will definitely keep the public’s attention on this for a while.”

The judge may have believed she was saving the Coleman plaintiffs from a long and fruitless court battle—and she may have been right—but for the women it felt like another threat.

“She came right out and said, ‘Ms. Aloe, if you don’t take this offer, it won’t be good for you,'” Aloe remembers. “What do you do? You’re on federal probation and you’re being threatened by a federal judge. You take the offer.”

In May 2021, the lawsuit settled before it could go to discovery—the pre-trial phase where the government would have been required to disclose all of its records related to the abuse at Coleman. In the end, the federal government paid the Coleman plaintiffs about $1.5 million combined. Some got more; some got less. Carleane Berman’s share came out to about $40,000 according to the Miami Herald.

“Honestly, it was a waste of time in my opinion,” Williams says. “Our lawyers were horrible, the government attorneys were ridiculous. We just got so dehumanized.”

Williams hadn’t even really wanted to join the lawsuit. After her release from Coleman, as soon as she finished her time at a halfway house, she changed her phone number and moved to a different state. Williams is a “blocker,” she says; she blocks traumatic things out to keep functioning. But when Berman called her, she couldn’t say no.

“I had joined the lawsuit with Carleane because she asked me to, and I could tell that she just really needed support,” Williams says. “Now I’m the only one left that can tell what happened for both her and me.”

A Horrific Failure

Ron Berman remembers his daughter seeming as happy as he had ever seen her in the first few months following her release from Coleman in September 2019. He remembers that one day she called him because she had taken his fixer-upper sailboat out onto Florida Bay to see the sunrise. This was somewhat concerning, because she didn’t know how to sail. He had to give her instructions on how to get the boat back through the canals to his dock. He had hopes that she would make a fresh start, get a job, maybe go to college.

Ten months after she was released from Coleman and two months after the lawsuit settled, Carleane Berman died in Saratoga, New York, from a drug overdose. She was 27 years old.

“She was just always fun and upbeat,” Williams remembers, “and you could never tell how much she was hurting inside unless you were really, really close to her.”

The incarceration of Carleane Berman for a nonviolent drug crime was a horror and a failure in every way. It took her out of the hands of one criminal predator and delivered her to another. It made a mockery of the justice system. It failed to rehabilitate her. In the end, it left her destroyed.

After her death, Ron Berman was cleaning out his truck, which he had lent to her, when he discovered a folder with documents from the lawsuit. Berman hadn’t known about what happened to his daughter in federal prison. Carleane had hinted at it once, but he hadn’t pried. She would tell him when she was ready, he thought.

There were signs he wished he recognized in retrospect. His daughter, who had transferred to Coleman from a prison in Texas to be closer to her family, had abruptly told them to stop visiting and cut off communication shortly after she arrived at the camp.

Flipping through the court papers, Berman realized for the first time what his daughter and all the other women had really gone through at Coleman.

“I was in tears,” Berman says. “All the women, it just became one story. I couldn’t believe what I was reading. This just can’t be happening in my country.”

It’s not happening anymore to women at Coleman, at least. Coleman doesn’t house women anymore. It transferred all the female prisoners out of the camp in 2021, two days before a PREA auditor arrived. This meant none of the women at Coleman were available to be interviewed for the PREA audit.

The Bureau of Prisons may be lurching toward some semblance of reform. Last year, then–BOP Director Michael Carvajal announced he was stepping down. He was last seen running down a stairwell in the Capitol building, away from Associated Press reporters who’d uncovered systemic sexual abuse at another federal women’s prison in California.

The Biden administration tapped Colette Peters, former director of the Oregon state prison system, to replace Carvajal. Peters has a reputation as a reformer, but now she faces the task of trying to change the culture of one of the largest federal agencies. In April, Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco told prison wardens gathered for a nationwide training session that sexual abuse in federal prisons must be rooted out.

As it stands, prison and jail staff rarely face legal consequences for substantiated sexual assault, according to data released by the Bureau of Justice Statistics. The data show that from 2016 to 2018, a period that overlaps with the abuse at Coleman, perpetrators of staff sexual misconduct were only convicted, sentenced, fined, or pleaded guilty in 6 percent of substantiated incidents in federal and state prisons.

The Justice Department is reportedly considering some steps to stop this from happening again. According to the Senate PSI report, the Justice Department inspector general is thinking of requiring the BOP’s Office of Internal Affairs to inform it of any evidence found in an administrative investigation “that could support a criminal investigation”—and to inform it before any interviews that would be protected by Garrity.

The BOP announced in December, shortly after the Senate PSI report was released, that it would prioritize applications for early release from victims of sexual misconduct. So far it has struggled to follow through on the promise. In April, an investigation by The Appeal uncovered “sexual violence, retaliation, and other constitutional abuses” at another federal prison in Tallahassee, Florida.

Congress continues to pressure the BOP from the outside, too. Sens. Jon Ossoff (D–Ga.), Mike Braun (R–Ind.), and Senate Majority Whip Dick Durbin (D–Ill.) introduced the Federal Prison Oversight Act earlier this year. The bill would require the Department of Justice’s inspector general to conduct detailed inspections of each of the BOP’s 122 facilities and, more significantly, to create an independent Justice Department ombudsman to investigate complaints.

At the end of last year, Biden signed the Prison Camera Reform Act, which will require the BOP to fix its broken surveillance camera systems and improve their coverage.

Incarcerated victims of sexual assault will also have a new avenue for relief. In April, the U.S. Sentencing Commission voted to approve updates to the federal sentencing guidelines that will make federal inmates eligible to apply for early release if they have been sexually or physically assaulted by BOP staff.

Meanwhile, the Coleman plaintiffs have been trying to piece their lives back together with varying success. One of the women interviewed by Reason says it took more than a year to start sleeping under blankets again. She had gotten accustomed at Coleman to not using sheets, because the cold kept her from drifting into too deep of a sleep. She didn’t want someone sneaking up on her.

Palomares got a job with the Florida Department of Corrections after resigning from the BOP. He lasted about six months at a state prison before the warden found out why he had resigned his previous job. According to records obtained by Reason, Palomares was fired for being less than truthful on his application, which required disclosure of any crimes, whether or not the case was prosecuted. He did not list the Coleman investigations.

As for Ron Berman, he is still working the phone and writing emails. He wants the statute of limitations on tort claims by federal inmates to begin after they’ve been released.

“My goal is very simple,” he says. “Those three individuals that raped my daughter, I want them in federal prison for life.”

In March, Berman met with several FBI agents and federal prosecutors to press them to prosecute the former correctional officers. In June, prosecutors asked him to write a letter explaining what he wanted from the Justice Department. “Unbelievable,” he texted. Did they even realize the scope of what had happened? Nevertheless, he will sit down and once again try to figure out how to tell this story.

*Correction: This sentence has been revised to clarify which guard assaulted Aloe while she had headphones on.

The post Federal Prison Guards Confessed to Rape and Got Away With It appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest https://ift.tt/cy0FdTA

via IFTTT