Last night, at President Donald Trump’s order, the United States stopped taking in any refugees, from any country in the world, for at least 120 days, in the name of “protecting the nation from foreign terrorist entry.” The far-reaching order, which marks a sharp reversal of decades’ worth of American policy, also slashed the annual target for the number of refugees accepted to 50,000, down from the original 110,000 for fiscal 2017 set by Barack Obama, and from the 85,000 refugees accepted in fiscal 2016. (The Obama administration consistently admitted around 75,000 refugees per year; only George W. Bush was stingier over the past 40 years.)

Refugees from Syria—currently the world’s largest producer of that unhappy category of humanity—are now banned indefinitely from the United States. (Last year Syria was the second-largest country of origin for U.S.-admitted refugees, at 12,500; this year the target had been 13,000.)

Meanwhile, every traveler from Syria, Iran, Iraq, Sudan, Libya, Somalia and Yemen, unless given special permission, is now barred from entering the United States for at least the next 90 days. Amazingly, that includes legal permanent residents who hold green cards but not U.S. citizenship, the Trump administration confirmed today. It’s an anguished day in Tehrangeles and other pockets of immigrants—many of them long since assimilated—from the seven disfavored countries.

What might this look like in numbers of humans affected? Pro Publica took a look last night and found:

About 25,000 citizens from the seven countries specified in Trump’s ban have been issued student or employment visas in the past three years, according to Department of Homeland Security reports.

On top of that, almost 500,000 people from the seven countries have received green cards in the past decade, allowing them to live and work in the United States indefinitely. […]

Citizens of Iran and Iraq far outnumber those from the other five countries among green card and visa holders. In the past 10 years, Iranian and Iraqi citizens have received over 250,000 green cards.

According to the Department of Homeland Security’s Immigration Handbook, these were the number of nonimmigrant admissions (minus diplomats/officials) to the U.S. in 2015 from the countries in question: Iran (34,915), Iraq (20,462), Syria (15,906), Yemen (5,226), Sudan (4,361), Libya (2,662), Somalia (318).

These sweeping changes were implemented so abruptly that refugees and other heretofore legal categories of traveler from the affected countries boarded their planes under one set of rules, only to find themselves detained upon landing. The New York Times and other outlets are filling up with anguished tales from bewildered passengers and their stranded families. Legal fights and executive-order interpretations are certain to follow.

The suspension of consular business as usual will hold until the Trump administration is satisfied that the countries of origin are fully cooperating with whatever “extreme vetting” procedures Washington ends up adopting.

Trump’s attitude toward Syrian refugees is one instance where his political base pushed him toward a more harsh position than the one he originally took. On Sept. 8, 2015, he

told Bill O’Reilly that “I hate the concept of it, but on a humanitarian basis, with what’s happening, you have to.” The next day, when asked about it by CNN, he sounded a more cautious note, saying “I think we should help, but I think we should be very careful because frankly, we have very big problems. We’re not gonna have a country if we don’t start getting smart.” On Sept. 15, he told Morning Joe that “the answer is possibly yes,” and then on Sept. 22, Campaign Manager Corey Lewandowski declared that a Trump White House would “take in zero” refugees.

Like many restrictionist conservatives, Trump has repeatedly conflated the Syrian refugees streaming through Europe with the far-less “military-aged male” cohort that makes it to the United States. He has mischaracterized the refugee-screening process as essentially not existing, and claimed falsely since the beginning of his campaign that Christian refugees from Syria were barred from entering the United States. To address that latter concern, his executive order seeks to “prioritize refugee claims made by individuals on the basis of religious-based persecution, provided that the religion of the individual is a minority religion in the individual’s country of nationality.” While the word “Christian” is nowhere to be found in the text of the order, Trump emphasized it in an interview last night with the Christian Broadcast Network:

“Do you know if you were a Christian in Syria it was impossible, at least very tough, to get into the United States?” Trump said. “If you were a Muslim you could come in, but if you were a Christian, it was almost impossible and the reason that was so unfair, everybody was persecuted in all fairness, but they were chopping off the heads of everybody but more so the Christians. And I thought it was very, very unfair.”

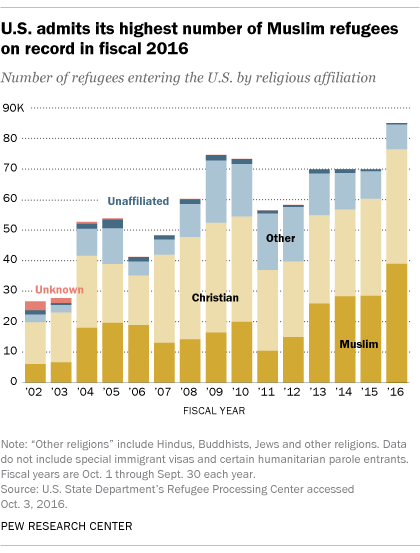

Since the onset of the Syrian civil war, around 96 percent of refugees take in the United States have been Muslim, and 2 percent Christian. This compares to a roughly 87/10 split in the population as a whole. (For one analysis of that disparity, see Christianity Today.) Overall, the Muslim share of the U.S. refugee population topped the Christian share for the first time in a decade last year, at 46 percent to 44 percent. It is true, despite critical commentary to the contrary this past week, that the United States always takes religion (and religious persecution, especially of minorities) into account when processing refugee claims. It is also true that Trump campaigned specifically on banning Muslims entry into the U.S., so there is certainly no reason to extend the benefit of the doubt here. And it’s hard to imagine a sharp reduction in refugees from war-torn majority-Muslim countries will translate into a net refugee gain among their Christian minorities.

Since the onset of the Syrian civil war, around 96 percent of refugees take in the United States have been Muslim, and 2 percent Christian. This compares to a roughly 87/10 split in the population as a whole. (For one analysis of that disparity, see Christianity Today.) Overall, the Muslim share of the U.S. refugee population topped the Christian share for the first time in a decade last year, at 46 percent to 44 percent. It is true, despite critical commentary to the contrary this past week, that the United States always takes religion (and religious persecution, especially of minorities) into account when processing refugee claims. It is also true that Trump campaigned specifically on banning Muslims entry into the U.S., so there is certainly no reason to extend the benefit of the doubt here. And it’s hard to imagine a sharp reduction in refugees from war-torn majority-Muslim countries will translate into a net refugee gain among their Christian minorities.

Trump’s order further emphasizes negative characteristics it will screen for that overlap perfectly with the cultural/security argument against Muslim immigration:

[T]he United States must ensure that those admitted to this country do not bear hostile attitudes toward it and its founding principles. The United States cannot, and should not, admit those who do not support the Constitution, or those who would place violent ideologies over American law. In addition, the United States should not admit those who engage in acts of bigotry or hatred (including “honor” killings, other forms of violence against women, or the persecution of those who practice religions different from their own) or those who would oppress Americans of any race, gender, or sexual orientation. […]

This program will include the development of a uniform screening standard and procedure, such as in-person interviews; a database of identity documents proffered by applicants to ensure that duplicate documents are not used by multiple applicants; amended application forms that include questions aimed at identifying fraudulent answers and malicious intent; a mechanism to ensure that the applicant is who the applicant claims to be; a process to evaluate the applicant’s likelihood of becoming a positively contributing member of society and the applicant’s ability to make contributions to the national interest; and a mechanism to assess whether or not the applicant has the intent to commit criminal or terrorist acts after entering the United States.

Will this order make the homeland safer? Reason offers some prior coverage skeptical of the claim. Ron Bailey in November that year assessed the literature and public record of refugees and terrorism within the United States, and concluded:

The researchers at the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) have found three cases where refugees admitted after 9/11 have been arrested on terrorism charges. In May 2011, the FBI arrested two Iraqis living in Bowling Green, Kentucky—Waad Ramadan Alwan and Mohanad Shareef Hammadi—for plotting to supply weapons and other material to Al Qaeda in Iraq. As the FBI noted, neither was “charged with plotting attacks within the United States.” Both were convicted and are serving long prison terms. […]

[N]one of the ones who were refugees committed a terrorist act on American soil. Second, and more important: None of these people, be they refugees or anything else, were sleeper agents who intentionally remained inactive for a long period, established a secure position, and then struck. None, in other words, fit the scenario being bandied about to justify keeping the Syrians out.

Some related thoughts from Jacob Sullum and Shikha Dalmia, plus some historical refugee fears from Jesse Walker. Then there’s this, from Reason TV:

from Hit & Run http://ift.tt/2kyhEdx

via IFTTT