Former President George H.W. Bush, who served one term in office from 1989 through 1993, is dead at the age of 94. By all accounts, he was an exceptionally kind, decent, and thoughtful individual and his service as a Navy pilot in World War II—he was awarded the Distinguished Navy Cross and shot down over the Pacific—reminds us of a time when seemingly casual, superhuman heroism by young twentysomethings was the order of the day.

Former President George H.W. Bush, who served one term in office from 1989 through 1993, is dead at the age of 94. By all accounts, he was an exceptionally kind, decent, and thoughtful individual and his service as a Navy pilot in World War II—he was awarded the Distinguished Navy Cross and shot down over the Pacific—reminds us of a time when seemingly casual, superhuman heroism by young twentysomethings was the order of the day.

Yet from a specifically libertarian view, there is little to celebrate and much to criticize regarding his presidency. With at least one notable exception, he did nothing to reduce the size, scope, and spending of government or to expand the ability of people to live however they wanted. If he was not as harshly ideological and dogmatic (especially on culture war issues) as contemporary conservatives, neither did he espouse any philosophical commitment to anything approaching “Free Minds and Free Markets.” There’s a reason he did not elicit strong negative responses or inspire enthusiasm: He lacked what he called “the vision thing.” He had no overarching theory of the future, no organizing principle to guide his policymaking. That’s not necessarily the worst thing in a president—we don’t need a maximum leader, after all—but it also means he squandered an opportunity to set the coordinates for a post-Cold War world in the direction of maximum freedom.

In his post-presidency years, Bush emerged as a genial, even comforting, distant presence on a political landscape that continues to drive toward absolute demonization and polarization of even the most trivial differences. That’s a role he was perfectly suited to play: As a one-term president who was the father of a very controversial president, he was a non-threatening loser to Democrats and Republicans alike, a Napoleon in exile who had no chance of coming back and taking power. At the same time, he lacked the moralizing overbearing of Jimmy Carter and the doltish qualities of Gerald Ford (who also bore a whiff of illegitimacy since he’d never been elected either president or vice president).

But George H.W. Bush’s primary legacy is as a president, despite a resume that is arguably the most impressive ever held by a chief executive. Before he took up residence in the White House, he’d been a two-term vice president, headed up the Central Intelligence Agency, was liaison to China in the early ’70s and was ambassador to the United Nations, ran the Republican National Committee, and served in Congress from Texas for two terms.

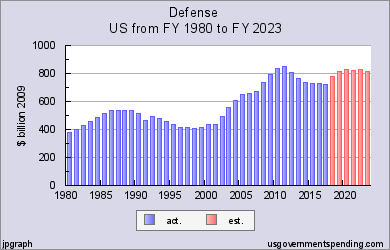

He helped to manage the end of the Cold War in Europe with restraint and diplomatic aplomb, and almost immediately oversaw the paying out of what was called “the peace dividend,” or reductions in year-over-year spending on defense. But as vice president, he was a big supporter of the Reagan administration’s war on drugs, and his unbridled and misguided enthusiasm for prohibition carried over into his own White House Years. Flipped out by high-profile deaths of movie stars such as John Belushi and athletes such as Len Bias, and fretting over the rise of crack cocaine, Bush appointed former Education Secretary William Bennett as America’s first head of the Office of the National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) or, as the position was called by its supporters, “drug czar.” Bennett publicly announced “there’s no moral problem” with beheading drug dealers because, you know, they’re bad people doing bad things. Bush moved quickly to internationalize America’s drug war, sending military supports and troops to far-flung countries willing to produce the drugs Americans demanded, further destabilizing places that were already shaky to begin with. Less than a year in to his presidency, he ordered “Operation Just Cause,” an ilegitimate invasion of Panama that burned “down entire neighborhoods of the capital and kill[ed] hundreds of people, to collar a single two-bit narcotrafficker,” our former ally Manuel Noriega.

Then there’s the defining foreign-policy act of his presidency: the Gulf War, or “Operation Desert Shield.” Pitched as an effort to restore internationally recognized boundaries after Saddam Hussein’s Iraq invaded and occupied Kuwait, the Gulf War ultimately solved no problems and instead set the table for the quagmire in which the United States is still mired. In summer of 1990, Saddam Hussein met with U.S. Amb. April Glaspie about the tensions between Iraq and Kuwait. Glaspie said, “We have no opinion on the Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait.” While there remains an argument over whether Glaspie was following Bush administration orders or injecting her own interpretation of U.S. interests, Stephen M. Walt writes, “It is clear from the cable that the United States did unwittingly give a green light to Saddam, and certainly no more than a barely flickering yellow light” to invade. Which Saddam did a week later.

To his credit, President Bush assembled a truly international coalition that included Israel and all Arab and Muslim countries in the Middle East, worked in conjunction with (though not subservient to) the United Nations, and limited the scope of the invasion to pushing Iraq out of Kuwait and subsequently containing Saddam Hussein. As Jonathan Rauch noted here, shortly after the 9/11 attacks:

The goal of the Gulf War, for Bush and the Arab allies alike, was not to impose a new order on the region but to restabilize the old one. Strategically speaking, that meant caging the overweening Saddam, not toppling him. Moreover, until 1990 Saddam had been a savage bully, but one America had done business with. It was reasonable to expect that after the fighting he might settle down, play by the rules, and pocket billions in diverted development aid like any self-respecting kleptocrat.

Needless to say, it didn’t turn out that way. The United States did nothing to aid the immediate post-war popular uprisings that Bush himself cheered on, earning the distrust of the local populace. Saddam did not become someone we could do “business” with in any meaningful way, and the region was hardly stabilized by that first U.S.-led Gulf War.

Needless to say, it didn’t turn out that way. The United States did nothing to aid the immediate post-war popular uprisings that Bush himself cheered on, earning the distrust of the local populace. Saddam did not become someone we could do “business” with in any meaningful way, and the region was hardly stabilized by that first U.S.-led Gulf War.

Indeed, the only way in which the first Gulf War looks good is in comparison to the second one that took place at the direction of George W. Bush. But that doesn’t mean the first Gulf War was a legitimate act of American defense policy, which should be aimed at protecting U.S. lives and property, not policing all the borders of all the countries in the world. There’s a strong case to be made that the relative ease of the immediate and overwhelming military victory by U.S.-led troops over Iraq in 1991 emboldened President Bill Clinton to become more promiscuous about overseas interventions, a tendency that Bush II also betrayed. Kicking “Vietnam Syndrome,” or a sense that the United States was relatively impotent when it came to shaping world events via military intervention, continues to extract a high cost for Americans and foreigners alike. Even as H.W. Bush vaguely invoked a post-Cold War “new world order,” he effectively invented the role of the United States as the world’s policeman, a role that presidents, with the possible exception of Donald Trump, continue to glory in.

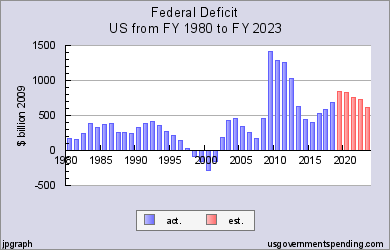

On the domestic side, Bush is best remembered for breaking his campaign promise of “No new taxes,” which he did to broker a 1990 budget deal with the Democrats. The legacy of the 1990 budget deal, which promised spending cuts of two dollars for every dollar in tax increases, is hotly disputed, both in its budgetary and political effects. The main provision increased the top marginal income tax rate from 28 percent to 31 percent and even critics of the plan agree it generated a total of about $137 billion in new revenue; champions of the plan credit it with setting the stage for the budget surpluses of the late 1990s.

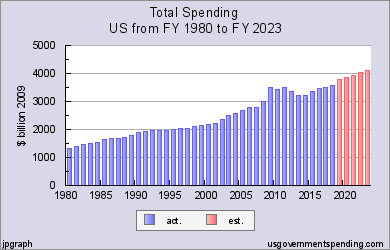

This much is certain, and should resound today, when our budget situation is much more dire in terms of spending, revenue, and deficits. On the spending side, the plan constrained the rate of spending growth but didn’t actually propose year-over-year cuts. As Reason‘s Charles Oliver noted in 1990, the need for a budget deal occurred because the government was overshooting mandated deficit-reduction targets set in the mid-1980s by about $60 billion out of a budget than totaled $1.2 billion. What happened if the government spent too much, asked Oliver?

This much is certain, and should resound today, when our budget situation is much more dire in terms of spending, revenue, and deficits. On the spending side, the plan constrained the rate of spending growth but didn’t actually propose year-over-year cuts. As Reason‘s Charles Oliver noted in 1990, the need for a budget deal occurred because the government was overshooting mandated deficit-reduction targets set in the mid-1980s by about $60 billion out of a budget than totaled $1.2 billion. What happened if the government spent too much, asked Oliver?

All that happens is that federal spending will automatically be cut across the board by that amount. Since the federal budget is over $1.2 trillion, it will only have to be cut by about 5 percent. Does anyone really think that there isn’t 5 percent of fat in the federal budget?

Of course, Congress can avoid automatic cuts by making reductions of its own. There are plenty of targets for the budget ax. The Bush administration already plans a 2 percent to 5 percent reduction in defense spending. Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Colin Powell has said that Pentagon spending could be cut by 25 percent without hurting America’s defenses. Some outside experts put the figure closer to 50 percent. Still, taking Powell’s estimate but speeding up his timetable slightly, we could cut defense spending by about $75 billion next year; that’s $62 billion more than is currently planned.

We could scale back domestic spending, too. Congress could cut farm subsidies, slow cost-of-living rises in social programs, and even eliminate controversial agencies such as the National Endowment for the Arts….

It all depends upon Congress and the president agreeing to use the peace dividend to reduce the deficit, not spending that money on new social programs.

We know how that turned out, of course. It remains unclear whether Bush’s breaking of his tax pledge was the reason he ended up losing to Bill Clinton in 1992. For some of 1991, Bush basked in post-Gulf War approval ratings above 90 percent (!), but a recession caused in part by tight money, fallout from the Savings & Loan scandal, fear of new taxes, and a tight money supply. As did the emergence of Ross Perot, who carried a Texas-sized grudge against Bush and clearly drained support directly from him in the general election.

Bush will be remembered as a decent man but the reverberations of his domestic and foreign policy failures leave little for libertarians to cheer.

from Hit & Run https://ift.tt/2Q88Mz0

via IFTTT