“By going into lockdown,” New York Times science writer Carl Zimmer matter-of-factly reports, “Massachusetts drove its reproductive number down from 2.2 at the beginning of March to 1 by the end of the month; it’s now at .74.” Zimmer is talking about the number of people the average carrier infects, and if the Massachusetts lockdown really did cut that number by two-thirds, it would be strong evidence that such policies are highly effective at reducing virus transmission. The truth, however, is rather more complicated.

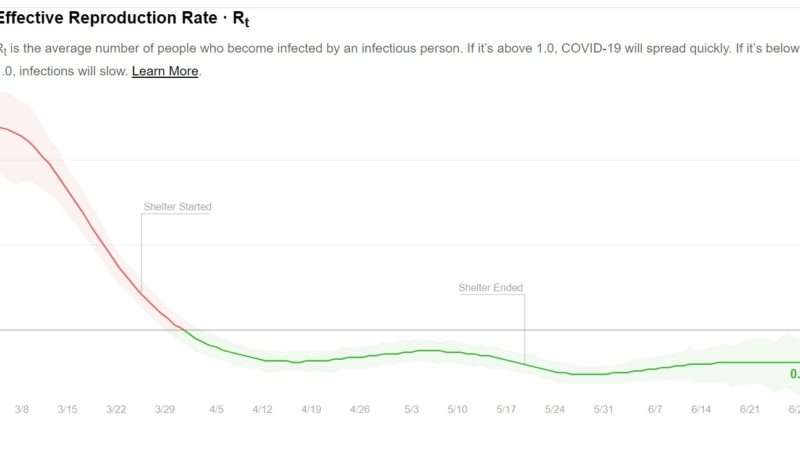

Zimmer links to a chart that shows the reproductive number in Massachusetts falling precipitously in March. But that downward trend began more than three weeks before Gov. Charlie Baker issued his business closure and stay-at-home orders. By the time Massachusetts officially locked down on March 24, the number had fallen from 2.2 to 1.2. That decline continued during the lockdown, falling to a low of 0.8 by May 18, when the stay-at-home order expired and Baker began allowing businesses to reopen. It is therefore possible that closing “nonessential” businesses and telling people to stay home except for government-approved purposes reinforced the preexisting trend. But the lockdown had no obvious impact on the slope of the curve.

The reproductive number continued to fall sharply until the end of March, when it dropped below one, which indicates a waning epidemic. The drop then slowed, and the number fluctuated, going up and down a bit but always staying below one. Since the lockdown was lifted, the picture has stayed pretty much the same. The estimate for yesterday was 0.8, which is a bit surprising if you believe the lockdown was crucial in keeping the number low. Although it has been more than a month since Baker started reopening the state’s economy, virus transmission has not been notably affected. Newly confirmed cases, hospitalizations, and daily deaths are all trending downward.

If you are a fan of lockdowns, you can look at these numbers and conclude that the policy has been a smashing success in Massachusetts, as Zimmer seems to believe. But if you are at all skeptical of the marginal impact that lockdowns had at a time when Americans were already moving around less and striving to minimize social interactions (as shown by cellphone and foot traffic data as well as estimates of the reproductive number), you have to wonder how Baker’s orders reached back in time to affect behavior that happened before they took effect. Trends in other states pose a similar puzzle.

Even if we give Baker’s lockdown full credit for positive trends in Massachusetts after March 24, it clearly is not responsible for reducing the reproductive number by 45 percent before then, even though Zimmer implies otherwise. And since the subsequent drop of 33 percent was smaller, it is logically impossible even to give the lockdown most of the credit for reducing transmission.

If voluntary changes in behavior account for the decline in transmission before the lockdown, it seems reasonable to assume that they played an important role after March 18 as well. How important is the crux of the dispute between Americans who think lockdowns were absolutely necessary to curtail the epidemic and Americans who question that belief.

The rest of Zimmer’s article, which focuses on the outsized role that superspreaders have played in the pandemic, lends support to the latter camp. “Most infected people don’t pass on the coronavirus to someone else,” he observes. “But a small number pass it on to many others in so-called superspreading events.”

Research in Hong Kong, for example, found that “just 20 percent of cases, all of them involving social gatherings, accounted for an astonishing 80 percent of transmissions.” Another 10 percent of carriers “accounted for the remaining 20 percent of transmissions,” meaning that 70 percent of people infected by the virus did not pass it on to anyone. Because the reproductive number is an average, it obscures the significance of superspreaders, which is nevertheless important in weighing COVID-19 control policies.

One hypothesis about superspreaders, Zimmer notes, is that some people tend to harbor more of the virus than others, making them more likely to pass it on. But environmental factors are also important. When a lot of people are packed together in an indoor space with poor ventilation, any carriers who happen to be there are much more likely to transmit the virus, especially if they are singing, talking loudly, coughing, or sneezing.

“A busy bar, for example, is full of people talking loudly,” Zimmer writes “Any one of them could spew out viruses without ever coughing. And without good ventilation, the viruses can linger in the air for hours.”

What are the policy implications? “Knowing that Covid-19 is a superspreading pandemic could be a good thing,” Zimmer notes. “Since most transmission happens only in a small number of similar situations, it may be possible to come up with smart strategies to stop them from happening. It may be possible to avoid crippling, across-the-board lockdowns by targeting the superspreading events.” He quotes British epidemiologist Adam Kucharski: “By curbing the activities in quite a small proportion of our life, we could actually reduce most of the risk.”

In other words, even if Zimmer is right to assume that locking down Massachusetts drove down virus transmission, that does not mean similar results could not have been achieved through less costly, more carefully targeted policies. If “it may be possible to avoid crippling, across-the-board lockdowns by targeting the superspreading events,” that seems like an option that politicians should have considered before closing down the economy.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2CRrdC1

via IFTTT