Tomorrow, March 17, is the anniversary of the Dalai Lama’s 1959 escape from a Chinese communist attempt to kidnap him. This post tells the story; it is the fifth in a series on the Tibetan Uprising.

Post 1 covered Tibet before the 1949 Chinese invasion, including the Tibetan government’s refusal to heed the 1932 warning of the Dalai Lama to strengthen national defense against the “‘Red’ ideology”. Post 2 was the Chinese conquest, followed by armed uprising of the people, precipitated by gun registration. Post 3 described the 1956-57 revolts, which liberated most of Eastern Tibet. Post 4 covered the creation of a unified national resistance in 1958, the Chushi Gangdruk.

These posts are excerpted from my coauthored law school textbook and treatise Firearms Law and the Second Amendment: Regulation, Rights, and Policy (3d ed. 2021, Aspen Publishers). Eight of the book’s 23 chapters are available for free on the worldwide web, including Chapter 19, Comparative Law, where Tibet is pages 1885-1916. In this post, I provide citations for direct quotes. Other citations are available in the online book chapter.

The plot to capture the Dalai Lama

As of early 1959, there were fifteen thousand Eastern Tibetans camped outside Lhasa, which is in Central Tibet. “They moved about the city fully armed and with trigger-happy eyes.” Mikel Dunham, Buddha’s Warriors: The Story of the CIA-Backed Tibetan Freedom Fighters, the Chinese Invasion, and the Ultimate Fall of Tibet 2619 (2004). The only remaining Tibetan supporters of communist China’s occupying “People’s Liberation Army” (PLA) in Lhasa were the dwindling numbers of collaborationist aristocrats.

To the immense embarrassment of the PLA, two thousand fighters of Chushi Gangdruk national resistance army attacked a three-thousand-man PLA garrison. In a six-hour battle, the Tibetans battered the PLA, and made off with a trove of weaponry. Gompo Tashi Andrugtsang, the creator and leader of the resistance army, then headed to the Central Tibet prefecture of Chamdo to urge everyone “to form their own armed force to defend their native towns and villages,” to block Chinese communications, and to “seize every opportunity for damaging and harassing the enemy war machine.” Gompo Tashi Andrugtsang, Four Rivers Six Ranges: Reminisces of the Resistance Movement in Tibet 93-94 (1973).

In early February 1959, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) announced that the Dalai Lama would visit Peking. Surprised, the Dalai Lama and the Tibetans suspected a kidnapping plot. The Chinese had recently been kidnapping and then murdering lamas by inviting them to Chinese social events. By March, the Lhasa population had tripled, with pilgrims arriving for the greatest of the Tibetan Buddhist religious events, the Monlam Prayer Festival.

The Dalai Lama was busy studying for the final exams for his Geshe Lharampa degree—the highest theological degree conferred in Tibet, equivalent to a Ph.D. Chinese officials began demanding that the Dalai Lama attend a theater performance at the PLA camp outside Lhasa on the afternoon of March 10. According to the invitation, he could not bring his customary armed bodyguards, nor could he tell the public about the visit. The Dalai Lama told the Chinese that he accepted.

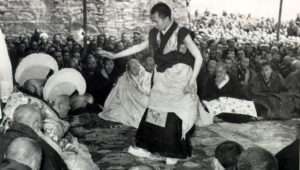

The news spread rapidly in Lhasa when the Dalai Lama’s officials announced special traffic restrictions for the road from Lhasa to the PLA camp. On the morning of March 10, thousands of Tibetans spontaneously assembled around the Dalai Lama’s Norbulingka palace, “armed and indifferent to personal safety.” Dunham at 269. About half the crowd were Khampas, Amdowas, or Goloks (Tibetan ethnic groups from well east of Lhasa). “[F]or the first time, Lhasans and Eastern Tibetans were acting as one.” Id. Lhasans who did not have firearms or swords brought their axes, picks, and shovels, or whatever else they could use as a weapon.

March 10, 1959, the Momentous Day

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) refers to March 10, 1959, as the “Lhasa incident” or the “March 10 Incident of 1959.” The Tibetan government-in-exile recognizes it as an official holiday, Tibetan Uprising Day. It was perhaps “The Most Momentous Day in Tibetan History.” Jianglin Li, Tibet in Agony: Lhasa 1959 at 135, 340 (2016).

The people of Lhasa reclaimed their city. They blocked incoming roads with barricades. For the first time since the PLA had arrived in 1951, the sovereignty in Lhasa was exercised by Tibetans. “The people were now the ruling body of Tibet.” Dunham at 269-70. They took over the National Assembly and the government. What was left of the Tibetan army distributed arms to the people. So did the Sera monastery, which had one of the biggest arsenals in Lhasa.

The PLA began preparing for action. Scouts took readings for artillery targeting. When a large PLA force advanced on the city, the defenders gathered. But the PLA movement was just a feint, to discover the size of the Tibetan forces.

In the Dalai Lama’s view, “[h]and to hand, with fists or swords, one Tibetan would have been worth a dozen Chinese—recent experience in the eastern provinces had confirmed this old belief.” But he knew that Lhasa could not defeat China’s heavy artillery. Dunham at 278-79.

March 17, the Dalai Lama escapes

On March 17, the Dalai Lama consulted the State Oracle. The oracle monk was brought forth, staggering under the weight of his ceremonial armor and 30-pound headdress. While other monks chanted or played the horns and drums, the oracle went into his dancing trance.

His face was distorted, his eyes bulging, his breathing labored. He appeared to swell in stature, no longer struggling under the costume’s weight. Suddenly he let out a piercing shriek.

“Go! Go! Tonight!”

He grabbed a pen and paper in a frenzy and jotted down a clear route map. Then his attendants rushed forward and relieved him of his enormous headdress. The deity departed from his body, and he collapsed onto the floor.

Li, Tibet in Agony, at 193-94. The State Oracle was believed to channel the Dalai Lama’s protector deity.

That afternoon, the communists lobbed a pair of mortar shells into the marsh next to Norbulingka palace—taken as a warning of the consequences of disobedience. The Dalai Lama escaped during the night of March 17. Very few people in Lhasa knew. Disguised as a soldier, with a rifle and without his glasses, the Dalai Lama was escorted by the Chushi Gangdruk and the Tibetan army, and also “protected by unseen resistance bands covering their flanks as they passed through the mountains.” Kenneth Knaus, Orphans of the Cold War: America and the Tibetan Struggle for Survival 165 (1999).

The Dalai Lama reasserts Tibetan independence and armed resistance

Shortly before entering India, the Dalai Lama repudiated the 1951 Seventeen Point Agreement, which the Chinese had violated, and which was the sole legal pretext for their presence in Central Tibet. He apologized for the Tibetan government’s issuance of anti–Chushi Gangdruk statements, which he explained were compelled and dictated by the Chinese. The Dalai Lama promoted Gompo Tashi Andrugstang, in absentia, to General (Dzasak) in the Tibetan army. The promotion letter stated: “the present situation calls for a continuance of your brave struggle with the same determination and courage.” Knaus at 166; Andrugtsang at 107 (copy of the letter, in Tibetan). Necessarily, the promotion recognized the Chushi Gangdruk as the army of the legitimate government of Tibet.

In the 1990s, the Dalai Lama reiterated his position that Tibetan resistance has been legitimate: “If there is a clear indication that there is no alternative to violence, then violence is permissible.” Knaus at 313. In the Dalai Lama’s understanding of Buddhism, motivation and results are more important than method. Therefore, violence is justifiable when motivated by compassion if it leads to good results.

The communists invade Lhasa

The communists did not discover that the Dalai Lama had escaped until March 19. They began claiming that the Dalai Lama had not chosen to flee, but instead had been abducted by imperialists and their accomplices. Later, in 1995 when the Dalai Lama’s campaign for Tibetan freedom was earning global attention, the CCP started putting out a story that Mao had intentionally allowed the Dalai Lama to escape. The tale has many factual weaknesses.

During the night of March 20, the PLA erected a barrier preventing movement between the eastern and western sides of Lhasa. Their attack began in the morning, supported by massive artillery bombardment. After two days of fierce building-to-building fighting, the PLA prevailed on the third morning as the defenders ran out of food and ammunition. Lhasa was in ruins, but the Dalai Lama was gone.

The PLA leadership brazenly lied to its troops. For example, the Tibetans were said to be “callous murderers” who tortured and killed people for the slightest infraction—a description more aptly applied to the CCP. Supposedly, the Tibetans slaughtered the laboring masses, and then used their skulls for rice bowls, their skins for drums, and female femurs for horns. Three decades later, at Tienanmen Square in Beijing, the PLA soldiers would be fed a different set of lies about the student protesters. And since the CCP controlled the media, most soldiers had no means of learning the truth. Timothy Brook, Quelling the People: The Military Suppression of the Beijing Democracy Movement 114-15 (1998).

The PLA counteroffensive

The PLA had grown increasingly proficient at counterinsurgency. They brought in non-Han cavalry, who as horsemen were far superior to the often inept Hans. The PLA improved at deploying mobile artillery. In places where it was not possible to use artillery, bombers were employed. When weather or terrain obstructed bombers, scout planes could still report the movement of resistance groups. Most importantly, the Chinese had spent the previous decade building a strong road and airport network in Central and Eastern Tibet. Although the Tibetans could and did cause trouble for Chinese supply convoys, the PLA forces in the field never ran out supplies.

An April 1959 PLA counteroffensive in Lhoka (a prefecture south of Lhasa) captured several strategic towns. The Chushi Gangdruk in the region, exhausted and running out of supplies, took the Dalai Lama’s advice and used their last chance to escape to India.

By mid-1959, control of the tempo of warfare had shifted to the PLA. The rebels, rather than being able to attack at times and places of their choosing, were trying to outrun PLA pursuit and were having to fight several engagements per week to do so. Eventually, many of them escaped to Nepal or India. They also guided other Tibetans past Chinese lines, and to the border. Cumulatively, eighty thousand Tibetans escaped.

As the PLA advantages grew, the rebels should have dispersed into smaller groups, which would have been harder to detect. If the fighting men had split into small guerilla bands, they could have kept operating for a long time. But the men would not abandon their defenseless families, and they needed to keep their herds with them for food. So the resistance camps were large and moved slowly.

Further from the border, other resistance fighters, with no opportunity to escape, kept up the fight. By this time, they were no longer attempting to liberate territory, but simply to conduct raids on enemy forces. The Goloks of Amdo province, too far north to flee to another country, continued their resistance.

By the fall of 1959, most of Tibet was back under PLA control, except for parts of Kham. There, the Khampas continued to disrupt Chinese conveys and their effort allowed “untold thousands of Tibetans to make their way safely to the border—a major contribution that has often been overlooked by Western historians.” Knaus at 340-41 As for Central Tibet, the resistance in outlying areas continued until 1962.

Tired of armed Tibetans, the Chinese forbade the Tibetan men’s tradition of wearing swords. About half the men were put into prisons and worked to death. The communization of Tibetan culture and religion, already well underway in Eastern Tibet, was fully inflicted on Central Tibet. The policy continues to this day.

In April 1959, the Tibetans set up a government in exile, at Dharamasala, India, which continues to this day. The government in exile is for all Tibetans, regardless of province of origin or religion. The government is democratic, and provides education from kindergarten through high school.

The CCP’s Political Commissar for Tibet, General Tan Guansen, might have thought he had earned a lifetime of respect from Mao’s regime. But during the Cultural Revolution that began in 1966, he would be purged as a supposed “capitalist roader.”

Next post: The resistance continues, and prevents a genocide.

The post Tibet's armed resistance to Chinese invasion appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest https://ift.tt/b4GZa0z

via IFTTT