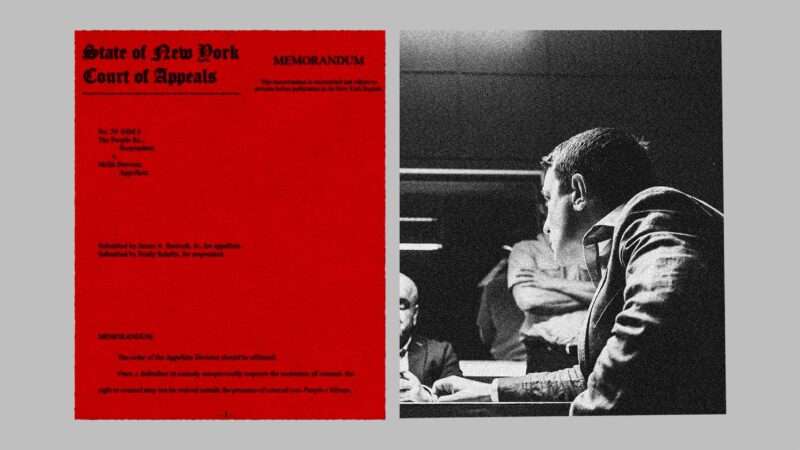

A teenager who asked to call his attorney but was denied the opportunity by police did not have his rights violated, the New York Court of Appeals ruled this week, reinvigorating a debate around what linguistic specificities are necessary to firmly and unequivocally invoke your Miranda rights.

In May 2016, Malik Dawson, then 19, was arrested for allegedly sexually assaulting a woman in Albany, New York, the week prior. When asked if he’d like to call his lawyer, the following exchange took place between Dawson and the detective:

Detective: Do you understand each of your rights?

Dawson: Yeah, definitely. I just wish that I’d memorized my lawyer’s number. He’s in my phone. Is it possible for me to like call him or something?

Detective: Do you want your lawyer here?

Dawson: Right now?

Detective: Yeah.

Dawson: If I could get a hold of him ’cause I don’t know his number; it’s in my phone.

Detective: OK.

Dawson: But you could still tell me what’s going on though, right?

Detective: No, I can’t talk to you if you if you want your lawyer here and you already said you did, so let’s, you know what, let’s give him a call.

But when the detective returned to the interrogation room, he came without Dawson’s phone. Instead, he said: “Here’s the deal, I’m just going to ask you flat out, because we’re in the middle of this and this is something we could potentially resolve—do you want your lawyer here or do you want to just figure this out?” Dawson responded that he wanted to “figure this out.”

As the detective began questioning Dawson about the alleged assault, Dawson insisted the encounter was consensual. The detective then told Dawson that if he were apologetic, it might work in his favor. So, without counsel present, he penned a letter to the victim admitting guilt and saying he was sorry.

Whether or not the detective violated the Constitution in demurring at Dawson’s request for an attorney is the subject of the New York Court of Appeals’ recent decision. “Here, there is support in the record for the lower courts’ determination that defendant—whose inquiries and demeanor suggested a conditional interest in speaking with an attorney only if it would not otherwise delay his clearly-expressed wish to speak to the police—did not unequivocally invoke his right to counsel while in custody,” the majority wrote.

Associate Judge Rowan D. Wilson dissented. “Here, Mr. Dawson unequivocally invoked his right to counsel—the record supports no other conclusion,” he said. “As is clear from the quoted portion of the colloquy with the detective, he twice said he wanted to call his lawyer, and the detective twice expressly stated that he understood Mr. Dawson had asked to call counsel and therefore the detective could no longer speak to Mr. Dawson….An unequivocal request does not require ‘magic words.'” (It is illegal for the government to continue questioning the accused after he has affirmatively invoked his desire for an attorney.)

This isn’t the first time that granular language choices have been at the center of such disputes.

Consider the case of Warren Demesme, who told police in Louisiana that he wanted to speak to a “lawyer dog.” He was not provided with one, and the Louisiana Supreme Court ruled that his rights were not violated because the request was too ambiguous.

That case, which was decided in 2017, got quite a bit of attention, with some deriding the absurd idea that any officer could have reasonably thought Demesme wanted to speak with a pet as opposed to an attorney. But even that decision was not so cut and dry. “Demesme obviously meant ‘friend,’ not the animal, and the police surely understood that. So if that’s the criticism, it seems pretty fair.” writes Orin Kerr, a law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, for the Volokh Conspiracy. “I think the ambiguity is not in the word ‘dog’ but in what Demesme said before that….On one hand, he did say ‘give me a lawyer.’ On the other hand, that phrase seems to have some conditions on it. He only wants a lawyer, he says, if the police think he did it.”

In other words, whether or not someone has actually invoked their right to counsel is, to some degree, subjective, though it can have far-reaching consequences in a defendant’s case. “The detective’s statement that ‘this is something we could potentially resolve’ — after having confirmed Mr. Dawson’s request to contact his counsel — is particularly concerning,” wrote the dissenting judge in Dawson’s case. “The statement implied that Mr. Dawson, if he were to abandon his right to counsel, might be able to very quickly settle the matter without issue. Of course, nothing could be farther from the reality.” With the apology letter as evidence, Dawson was convicted and sentenced to seven years in prison, followed by 10 years of post-release supervision.

The post He Didn't Use the 'Magic Words' To Get Access to a Lawyer. Were His Rights Violated? appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest https://ift.tt/ngQV51c

via IFTTT