Authored by Kevin Muir via The Macro Tourist blog,

Over the Christmas break, the guys at MacroVoices created a special series about the future of the US dollar. It was supposed to be a bulls versus bears debate, but a problem became quickly apparent when all the participants found themselves agreeing, that over the long run, the US dollar was headed lower. They simply disagreed about the path.

Alhambra Investment Partner’s Jeff Snider believed the structural problems in the eurodollar market would cause a US dollar short squeeze that eventually forces a monetary reset which results in a much lower US dollar. While “Forest for the Trees” Luke Gromen and Morgan Creek Capital’s Mark Yusko held the view that the US dollar is in the process of losing its reserve currency status. While they didn’t agree with the speed at which this occurs, they were mainly on the same page – the long march lower for the US dollar had already started. And MacroVoices host Erik Townsend even jumped into the mix, and in a great addition, shared his views and concerns about the future of the US dollar from a societal point of view. Now, these synopses are probably doing great injustice to all the nuances of their arguments, but I think I got the big picture right.

Now if you made me choose a side, I must admit, I am partial to Luke Gromen’s argument that the US dollar has begun the process of losing its reserve currency status, but where I differ from most thinkers is the belief that this will eventually result in some great market crisis.

Do I think that a decade from now that the US dollar will be as dominant as today? Not a chance. With technology making transactions easier, I don’t see why commodities need to be predominantly priced in one currency. Capital is increasingly becoming more mobile. Financial transactions are converted into various currencies with remarkable ease. Why does there even need to be a reserve currency?

Often US dollar bulls, when pushing back against this idea, will counter and say – if the US dollar loses its reserve currency status, which currency will take its place? I would argue none. Who wants the exorbitant privilege?

But… but… but… I can hear it already – America funds enormous deficits at rates that the market only accepts due to its reserve currency status. To which I respond with a resounding – BS! If that was the case, then both Japan and Europe would be punished with sky-high interest rates. Instead they are funding their monster deficits with near zero interest rates. But… but… but…. they are pegging their rates, so that argument isn’t fair. Yeah, to that I would retort – the unholy trinity means you can’t control interest rates, have free capital movement, and not have it show up in the foreign exchange rate. Yet neither Japan and Europe is experiencing some massive decline in their currency, so I don’t buy that argument. The US dollar reserve currency status is not the reason the US is able its fund massive deficits. All reputable countries are able to fund their way-too-large deficits, so losing the reserve currency status is not going to result in some spike in US interest rates.

Why does no one examine the middle of the road possibility?

Which brings me to my main point. Why do so many strategists believe the problem of too much debt needs to be resolved in either a deflationary credit contraction, or alternatively a hyper-inflationary explosion? Why does no one examine a middle of the road possibility?

I agree there is no way we are going to grow our way out of our massive indebtedness. I am not some naive Pollyanna that believes Trump’s policies will usher in a Reagan type financial revolution that somehow magically grows the economy enough to right the debt burden. Not a chance. Nor am I some doom-and-gloomer that believes the growing debt needs to reset through a credit contraction that involves a painful 1929 style depression.

Here’s a thought – why can’t we have a decade-and-a-half of 4.5% inflation? Think about it. Assuming Central Banks underwrite the borrowing, fifteen years of that sort of inflation halves the debt in real terms. Sure it won’t be real growth, and there will be winners and losers from that sort of inflation, but make no mistake, it will accomplish what everyone admits needs to be done – the debt either needs to be destroyed, or inflated away.

Of course, there is a big risk that, in trying to accomplish this feat, Central Banks and governments are not able to accomplish a nice steady 4.5% inflation, and instead results in massive inflation volatility which produces economic uncertainty. There is no doubt that simply dialing 4.5% inflation for fifteen years is easier said than done, but it’s not out of the realm of possibility. Yet few are considering this outcome.

Back to today

No politician or Central Banker will admit this possibility out loud. They still mouth words about maintaining price stability, or having a strong currency. But let’s face it. The choice between a contractionary credit destruction event and inflating it away is easy. They will choose inflation each and every time.

That why ultimately, I believe that the path for all fiat currencies is clear – it’s lower. Yet, as my fellow Canadian, Bespoke Investments’ George Pearkes wrote me the other night, “Well, if you’re talking about exchange rates it’s by definition impossible for ‘all currencies’ to ‘debase into oblivion’…the world’s TWI (Trade Weighted Index) is always 1!”

George has correctly pointed out that currency debasement is a relative game. If the Yen is devalued through massive balance sheet expansion, then all the other countries’ currencies will be higher. One country’s inflationary tailwind becomes a deflationary headwind for everyone else.

Since the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, countries have passed around the deflationary baton. Japan was slow to expand their QE programs in the wake of the American-centric GFC. The end result was Yen strength that caused a change of government and the introduction of the radical Abeconomics.

Then in 2012, the ECB decided the crisis had passed, and it was time to shrink their balance sheet. In doing so, they also caused massive Euro appreciation (especially against their Japanese competitor who was in the process of devaluing the Yen). This Euro strength created the Euro-crisis of 2014, and ushered in negative rates in Europe.

And from 2014-16, the US dollar led the way higher. This US dollar strength was a big factor in the 2014 oil collapse led mini-credit crisis. The global economy struggled under the weight of a sharply rising US dollar.

But you are a fool if you believe that Trump and Mnuchin want a stronger dollar. And this was glaringly apparent when Mnuchin let slip how he really felt last week at Davos. From CNBC:

The dollar plummeted to three-year lows on Wednesday, its biggest one-day drop in 10 months, after Mnuchin suggested a weak greenback would be good for the U.S.

Mnuchin’s comments had echoed statements by President Donald Trump, who helped turn a market trend of a stronger dollar last January when he declared prior to his inauguration that the dollar was “too strong” and that U.S. companies couldn’t compete because of it – particularly against the Chinese.

In the ensuing days, both Trump and Mnuchin have attempted to walk back the damage, but make no mistake – they want a lower US dollar – they just can’t admit it out loud.

Already too strong for the Europeans

The past year has seen the European economy pick itself up off the mat. This strength has helped propel the Euro from 1.05 to 1.25.

Yet even this modest strength already has the ECB worried. From Reuters’ reporting of last week’s ECB conference:

“When someone says that basically a good exchange rate is good for exporters and it’s good for the economy and it’s good, that means it’s targeting the exchange rate,” Draghi said when asked about Mnuchin’s comments.

“That agreement (about not targeting the exchange rate), as subtle as you want, has been in place for decades now,” Draghi added.

The ECB is especially sensitive to the euro’s moves as any big rise in the currency could cut into inflation, threatening to reverse the impact of the very stimulus the bank has been providing over the past three years.

But Draghi’s comments that part of the euro’s gain may be related to the bloc’s strong economy, pushed the currency to $1.2538, its highest level since December 2014. Even a suggestion that rate hike expectations were premature, only pushed it back marginally, leaving it up nearly 1 percent on the day.

“If all this were to lead to an unwanted tightening of our monetary policy … then we will have to just think about our monetary policy strategy,” Draghi said, with particular reference to the U.S. statements.

The ECB is already threatening to not ease up on their printing due to the Euro’s strength.

So I ask you, do you really think that Central Banks are about to shrink their balance sheets anytime soon?

I would argue that they will never reduce them in a meaningful way.

I believe it is Jim Bianco who likes to remind readers that never in modern financial history has a Central Bank expanded its balance sheet through quantitative easing and then successfully shrunk it back down.

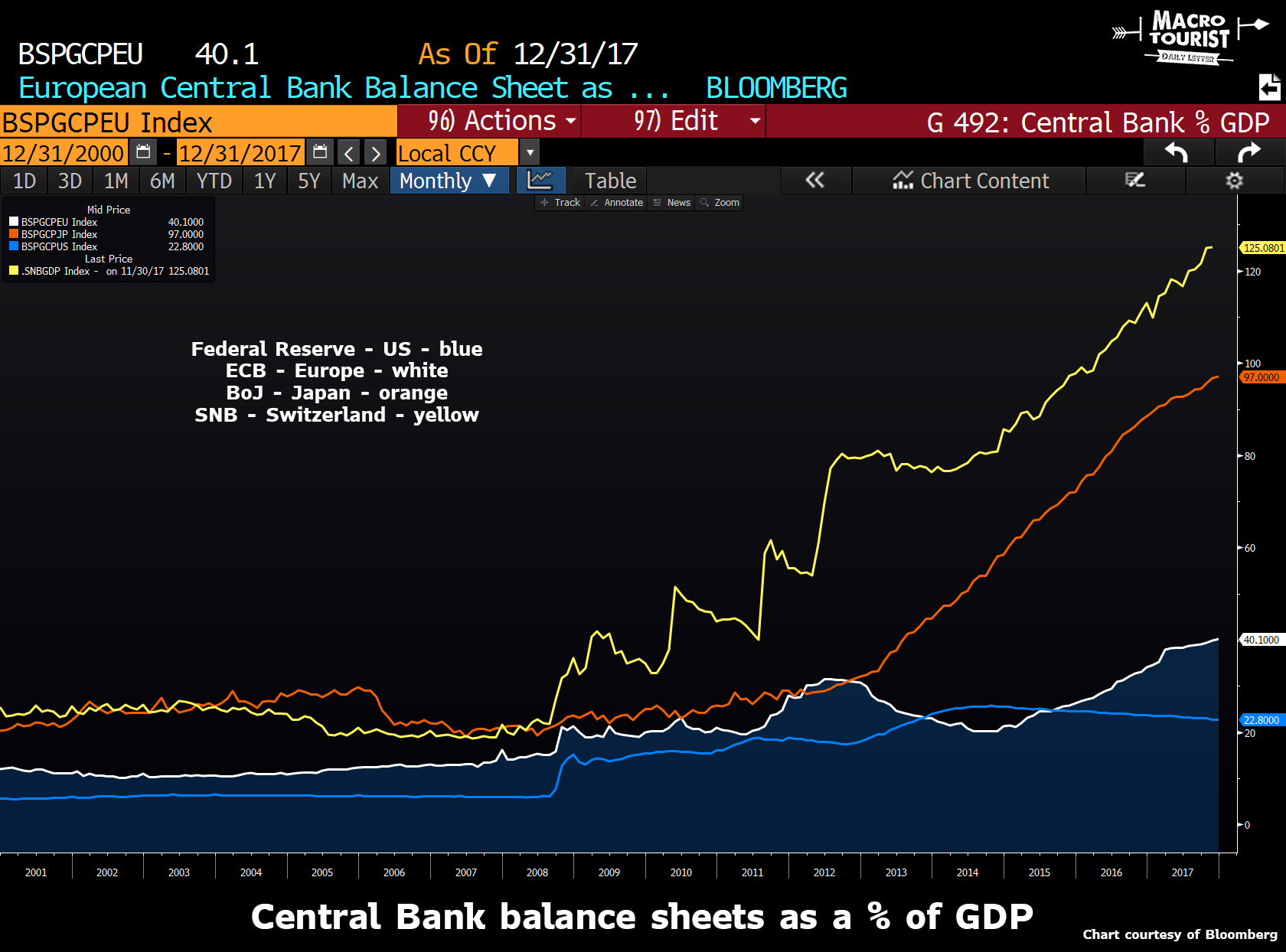

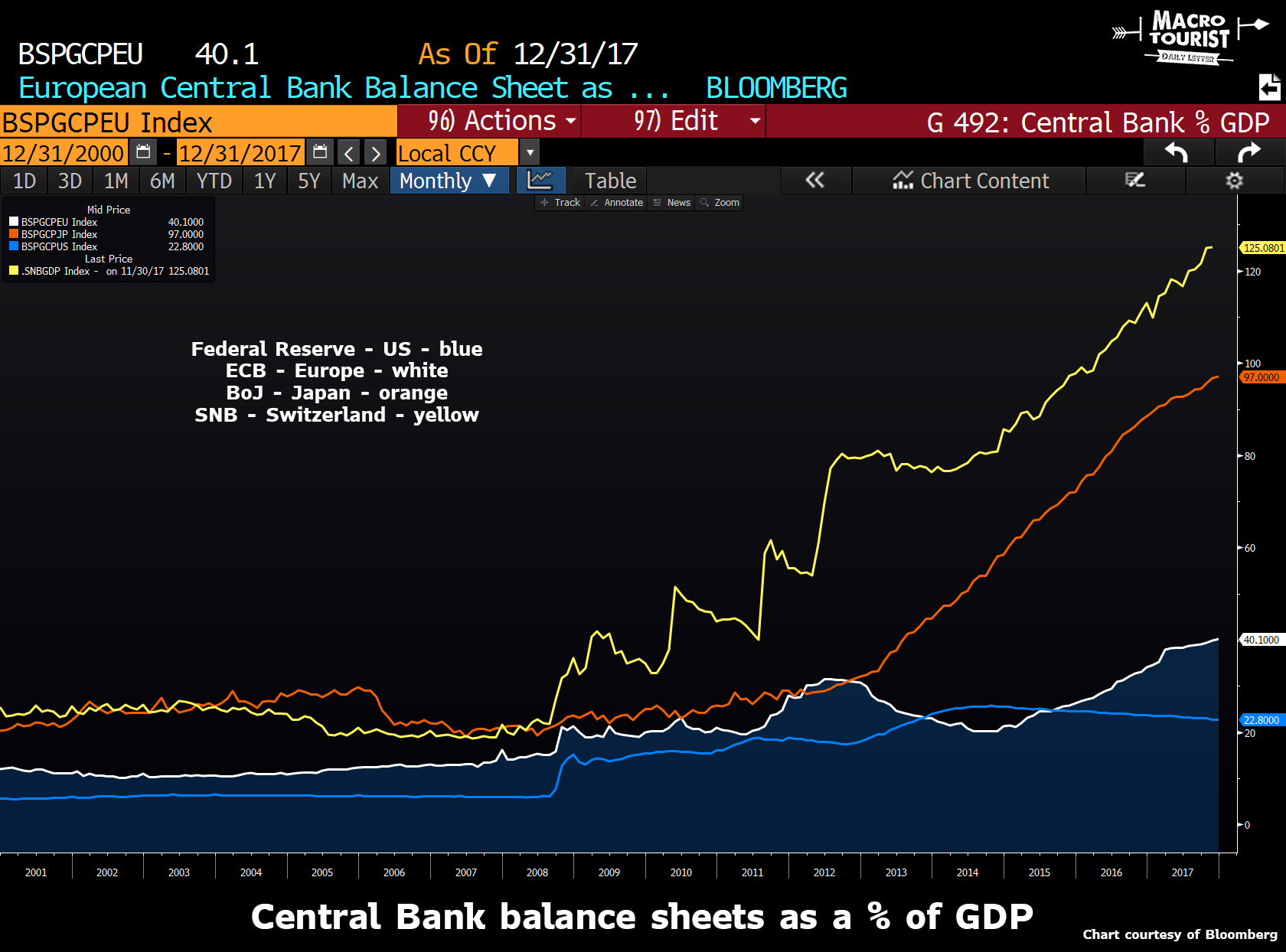

And looking at this chart, the trend seems pretty clear to me.

Feedback loop

If we assume that no one wants a strong currency, and that any sort of currency strength is met with Central Bank balance sheet expansion, or, in the case of Trump – threats of trade wars and expansionary fiscal policy, then it becomes clear that easy policies will continue, with different countries leading the charge at different times. So although the Trade Weighted Index always adds up to 1, against real assets, fiat currencies will be continually debased.

And this is not the end of the world. Inflation is heading higher, no doubt about that. But if governments can encourage it to be led by some wage inflation (increases in minimum wages are happening all over the world and Japan is even choosing companies for inclusion into their QE program based on their wage setting policies), then we might be on the cusp of a re-balancing.

Now don’t email me telling me that this is a terrible policy for governments to embark on. Could be. What do I know? But if it’s going to happen, then moaning about the social ramifications won’t help your portfolio one iota.

Central Bankers and governments will continually surprise with too much stimulus in the coming decades. They have to. There is simply no other choice that the public is willing to accept.

Which brings me to the current action in the foreign exchange markets. The US government has set out on a stimulative fiscal policy, and when combined with the revival of animal spirits with the deregulation and other pro-business initiatives, this has created an explosion of private sector credit creation. This in turn increases the supply of US dollars, and sends it lower.

The problem is that in the past, this has meant some deflationary effects for other countries. So at the margin, they are going to meet US policies with their own (relatively) easier policies. It ends up being a positive inflationary feedback loop.

Ironically, the more Trump pushes on the fiscal gas pedal, the more other countries will chase with easier policies of their own. And make no mistake, Trump is not going to ease up on his pro-growth policies. Now he might make a mistake and start a trade war, but again, that will simply mean an even lower US dollar, and even more expansionary policies by other countries.

US dollar is still expensive

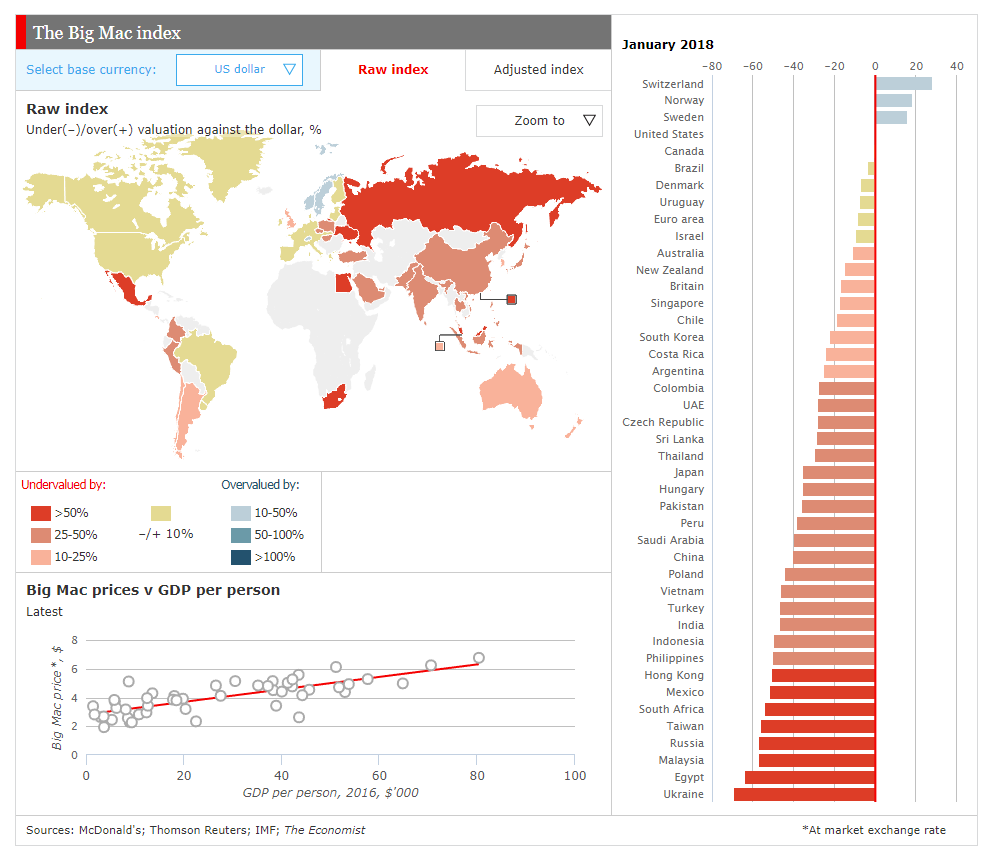

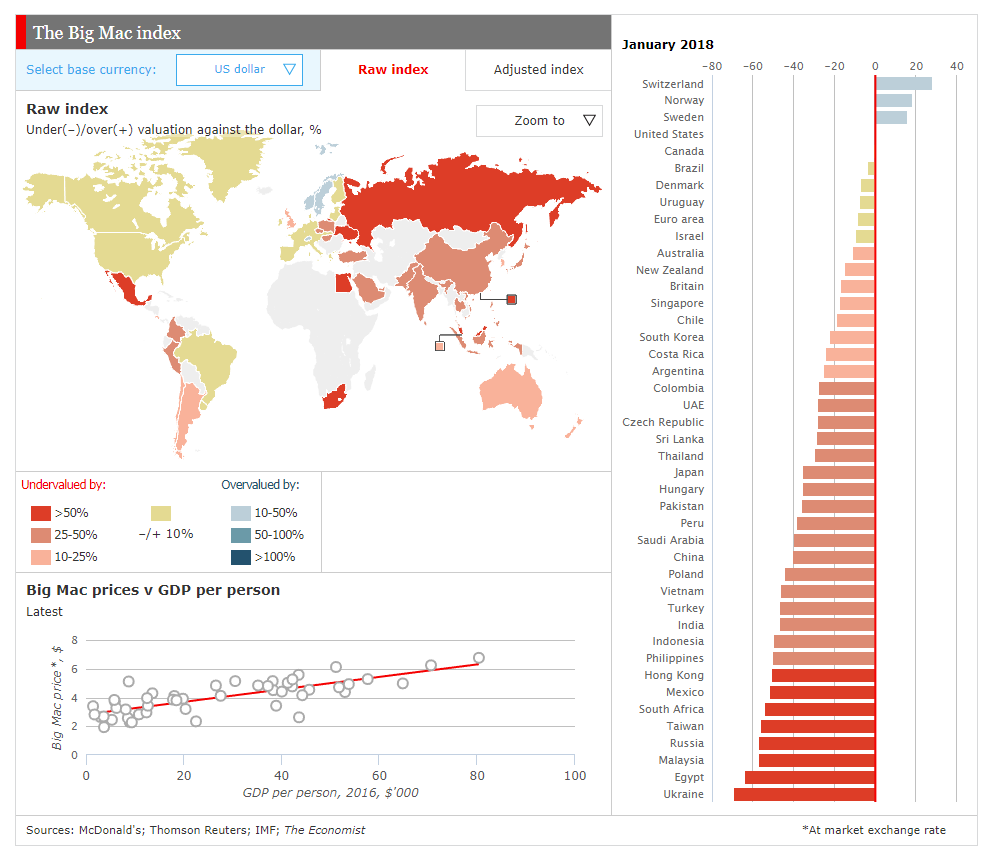

Although the US dollar has gone offered during the past year (declining from DXY 104 to 89), it is by no means cheap. Have a look at one of my favourite indicators, the Big Mac Purchasing Power Parity Index:

Only Switzerland, Norway and Sweden are more overvalued. Everywhere else is cheap compared to the US dollar.

Now I know, Big Mac pricing is not the kind of analysis to base your portfolio decisions. But if we think back to Luke Gromen and Mark Yusko’s theory that the US dollar is in the process of losing its reserve currency status, it will probably get a lot cheaper before fundamentals deliver a value floor.

Currencies often trend for months, and months, and sometimes even years, so there is nothing stopping this move from being the start of something bigger.

An alternative view

I am of the opinion that American economic expansion will actually result in a lower US dollar (more supply being created), but there are plenty who are bearish on the US dollar because they think the American economy is about to roll over. And even more confusingly, at the same time there are those like Jeff Snider who believe that a recession will cause a massive short squeeze in the US dollar as credit is destroyed as US dollars are paid back.

There can be no doubt it’s complicated. The reasons for either an economic slow down or acceleration can cause the US dollar to both rally or decline. To me, it’s important to look at whether US dollar credit is being created or destroyed.

But there are others who believe the flow of funds from managers choosing the most attractive destination for their capital means more. My favorite US-dollar-bull-yet-still-gold-bug buddy Santiago Capital’s Brent Johnson created this great presentation outlining his arguments for why the US dollar is poised to rally.

As I was watching, I realized that Brent was one of the few pundits willing to say the US dollar was headed higher – not because of structural problems in the Eurodollar funding market or from a short squeeze in US borrowers paying back money – but because the US dollar is best economy out there. I might not agree with Brent, but I felt a certain kinship with his lonely call. Often the best trades are the ones where the fewest agree with you. I joked with Brent that it almost made me want to join him on the US dollar long side.

The investor is in me is convinced Luke and Mark are right that the US has entered into a long period of decline, but the fact that MacroVoices couldn’t find a single bull to make the US dollar bull argument makes the trader in me think that Brent is going to be right in the coming weeks and months.

via RSS http://ift.tt/2BBtXxe Tyler Durden

FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe is out. While many expected him to retire this year, the abrupt timing of the announcement surprised many. The White House has denied that President Donald Trump’s open dislike of the man (due to Democratic Party donations to his wife’s failed campaign for the Virginia State Senate and the ongoing investigation of Russian collusion) played a role.

FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe is out. While many expected him to retire this year, the abrupt timing of the announcement surprised many. The White House has denied that President Donald Trump’s open dislike of the man (due to Democratic Party donations to his wife’s failed campaign for the Virginia State Senate and the ongoing investigation of Russian collusion) played a role.

The University of Cincinnati expelled a student, Tyler Gischel, after he had sex with a student who claimed she was incapacitated at the time. Gischel claims investigators ignored two critical aspects of his defense: that his accuser wasn’t as drunk as she claimed, and that she might have been romantically involved with William Richey, the university police detective who handled the case.

The University of Cincinnati expelled a student, Tyler Gischel, after he had sex with a student who claimed she was incapacitated at the time. Gischel claims investigators ignored two critical aspects of his defense: that his accuser wasn’t as drunk as she claimed, and that she might have been romantically involved with William Richey, the university police detective who handled the case.

A trade panel shot down a plan to put tariffs on imported jets late last week. It was a rare setback for American protectionists, who have been riding high recently.

A trade panel shot down a plan to put tariffs on imported jets late last week. It was a rare setback for American protectionists, who have been riding high recently.

Over the weekend, St. Louis writer and

Over the weekend, St. Louis writer and