Consider two recent examples of heterodox thought on COVID-19.

In a blog post, Robin Hanson (an economics professor at George Mason) was more worried than most about the novel coronavirus. He concluded that “we are probably already past this point of no return” and that one significant problem is “that our medical systems have limited capacities.” This post was published in mid-February, well before the idea to “flatten the curve” and maximize our health care response to the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself spread virally across the Internet. Hanson considered whether “controlled exposure,” that is “deliberately exposing particular people at particular times, according to a plan” might be a good way of dealing with the epidemic.

Such a plan shouldn’t just expose random people early, as they’d be likely to infect others around them. Instead, groups might be taken together to isolated places to be exposed, or maybe whole city blocks could be isolated and then exposed at once. Exposed groups should be kept strongly isolated from others until they are not longer very infectious.

Those who work in critical infrastructure, especially medicine, are ideal candidates to go early. Such a plan should only expose a small fraction of each critical workforce at any one time, so that most of them remain available to keep the lights on. If critical workers could be moved around fast enough, perhaps different cities could be exposed at different times, with critical workers moving to each new city to be ready to keep services working there.

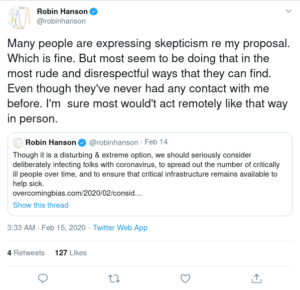

Angry reaction predictably followed, leading to the following Hanson tweet:

Hanson was undeterred and elaborated on his proposal in a series of posts, plus a spreadsheet model, with modifications discussed here. Lately, Hanson has made a distinct but related argument, for variolation, i.e. voluntary deliberate infection at a low dose, as was used for smallpox.

Meanwhile, Richard Epstein wrote an article on March 16 entitled “Coronavirus Perspective.” The article in its current form offers the following conclusion:

From this available data, it seems more probable than not that the total number of cases world-wide will peak out at well under 1 million, with the total number of deaths at under 50,000 (up about eightfold). In the United States, if the total death toll increases at about the same rate, the current 67 deaths should reach about 5000 ….

In the original publication, he concluded that U.S. deaths would reach 500; he later attributed this to a math error, acknowledging that there was no reason to think that the United States would account for only 1% of the death rate. In the revision (on March 24), he acknowledged that his revised estimate “could prove somewhat optimistic.”

Epstein claimed that other models “underestimate the rate of adaptive responses, which should slow down the replication rate.” On one hand, Epstein’s thesis is that death rates will be low because people are taking steps to minimize contact with one another. On the other hand, he calls the measures that the government has taken “draconian,” arguing “that even though self-help measures like avoiding crowded spaces make abundant sense, the massive public controls do not.” Thus, if Epstein’s bottom-line forecast of 5,000 deaths proves roughly correct, that would not resolve the underlying question whether Epstein’s public policy recommendation was correct. If deaths are relatively low, we won’t know (though could estimate with various assumptions) whether this is because of government mandates or because of voluntary distancing. Some but not all of what the government mandates would occur voluntarily, and it’s hard to determine how much. Epstein’s forecast is falsifiable (and, many sophisticated observers believe, likely to be falsified, as “superforecasters” estimate that it is probable that there will be between 35,000 and 350,000 deaths), and if his forecast is wrong, that would cast serious doubt on his public policy recommendation.

Epstein also made an evolutionary argument, that adaptive responses such as handwashing will exert selection pressure on the virus, so that the strains of the virus that survive will tend to be less virulent strains:

Start with the simple assumption that there is some variance in the rate of seriousness of any virus, just as there is in any trait for any species. In the formative stage of any disease, people are typically unaware of the danger. Hence, they take either minimal or no precautions to protect themselves from the virus. In those settings, the virus—which in this instance travels through droplets of moisture from sneezing and bodily contact—will reach its next victim before it kills its host. Hence the powerful viruses will remain dominant only so long as the rate of propagation is rapid. But once people are aware of the disease, they will start to make powerful adaptive responses, including washing their hands and keeping their distance from people known or likely to be carrying the infection. Various institutional measures, both private and public, have also slowed down the transmission rate.

At some tipping point, the most virulent viruses will be more likely to kill their hosts before the virus can spread. In contrast, the milder versions of the virus will wreak less damage to their host and thus will survive over the longer time span needed to spread from one person to another. Hence the rate of transmission will trend downward, as will the severity of the virus. It is a form of natural selection.

One key question is how rapidly this change will take place. There are two factors to consider. One is the age of the exposed population, and the other is the rate of change in the virulence of the virus as the rate of transmission slows, which should continue apace. By way of comparison, the virulent AIDS virus that killed wantonly in the 1980s crested and declined in the 1990s when it gave way to a milder form of virus years later once the condition was recognized and the bath houses were closed down. Part of the decline was no doubt due to better medicines, but part of it was due to this standard effect for diseases. Given that the coronavirus can spread through droplets and contact, the consequences of selection should manifest themselves more quickly than they did for AIDS.

The Epstein article appears to have had greater influence on public officials than Hanson’s. The Washington Post reported, “Conservatives close to Trump and numerous administration officials have been circulating an article by Richard A. Epstein of the Hoover Institution, titled ‘Coronavirus Perspective,’ that plays down the extent of the spread and the threat.” One can speculate that the article may have affected policy, but it is hard to tell for sure.

The New Yorker today published an interview by Isaac Chotiner of Epstein, in which Epstein elaborates in particular on his evolutionary view. The interview includes parenthetical responses from infectious-disease experts and epidemiologists disagreeing with some of Epstein’s claims. For example, one expert denies that there is any “evidence that there are strong and weak variations of the coronavirus circulating.” And another states that there is no evolutionary tendency of the virus to weaken, explaining, “To the extent we see that evolution taking place it is usually over a much vaster timescale.”

There is a great deal of criticism of Epstein’s responses in the interview on Twitter, much of it by scholars I greatly admire. Some of the critique uses the episode to take a swipe at the legal academy in general. One of the most thoughtful critiques is by Rex Douglas, a data scientist. Among other points, he argues that state-of-the-art epidemiological models do take into account that R0 (the measure of infectiousness) is likely to decline over time. It’s not clear to me whether that’s because of an evolutionary tendency or simply because there are fewer people to infect. But I think that it’s a fair point that of course epidemiological models take into account how infection rates change over time.

At least to me, the exchange has been helpful in highlighting the particular areas of disagreement: Epstein, who points out that he has read widely in evolutionary theory, would expect the virus to weaken greatly through natural selection. At least a few epidemiologists, no doubt also conversant in evolutionary theory, do not believe that this is a significant consideration, and in any event, epidemiological models already account in at least some way for decreasing infectiousness over time. My own instinct at this point is to think that Epstein’s estimate of fatalities is too low and also that Epstein’s confidence in his critique was too high. But I would welcome further discussion and explanation, if for no other reason that I am curious about how much if at all evolutionary forces matter within the relevant time frame.

It is often useful for an intelligent, well-read outsider to a literature to push the experts to explain their assumptions more clearly. Perhaps the vast majority of the time, when an outsider to the literature makes a critique, it will turn out that the critique is flawed, and maybe it will waste the time of insiders who feel obliged to respond and clarify. But time spent clarifying foundational assumptions and points that a thoughtful outsider might miss is not really wasted. And every once in a while, an outsider may identify a genuine problem. Intellectual history is littered with once accepted beliefs ultimately changed as a result of the insistence of contrarians. Epstein complains in his interview that Chotiner is looking to make Epstein out to be a crackpot. I don’t think that Epstein is a crackpot, but even if he were, we all know that sometimes the crackpot hits the jackpot. If there were some major flaw in conventional thinking, we would like it to be exposed during an emergency as quickly as possible. Change within a literature often occurs over generations. Policymakers should provisionally accept widely-held views of experts, but outsiders can be helpful in probing those views.

Epstein’s article, moreover, can be credited with highlighting the point that even if the government does not mandate social distancing and lockdowns, people will not behave as they ordinarily would. Neil Ferguson originally predicted that the U.K. could suffer 500,000 deaths, but now projects more like 20,000. This is not a change in the underlying model, but rather an updated calculation based on an exogenous change in government policy. But can we really credit policy change for the entire difference? The 500,000 figure is based on a model of “what would have happened if no interventions were implemented (and Rt = R0 i.e. the initial reproduction number estimated before interventions).” But surely, Epstein is right that even absent government interventions, voluntary actions from people worried about getting sick (and worried also about then passing along their sickness) would lower the initial reproduction number. It is very difficult to disentangle reductions in the reproduction number attributable to government action from reductions in the reproduction number attributable to voluntary action, because governments will tend to act when people start to get worried.

Epstein’s work thus adds some nuance to the debate (though that nuance was not the central point and has been lost in the broader discussion). We need to consider the marginal effect of various types of government interventions, relative to the behavioral changes that people would engage in on their own. That will allow for better assessment of marginal benefits and marginal costs of particular interventions. I don’t know that I would look to epidemiologists to answer that question (though they may have produced some useful work on this issue of which I am unaware). It seems like more of a law-and-economics issue, well within Epstein’s expertise. Unfortunately, it’s also not an issue on which there exists a methodology to produce conclusive answers, at least not yet. My own instinct is different from Epstein’s here. I tend to believe that fairly draconian government interventions are justified for the time being. But that instinct is also based in part on a law-and-economics point, that there is option value to delaying the virus and waiting for better information to develop, both about governmental interventions and about medical ones.

Could Epstein have been more careful here? He did conclude his article by stating, “Perhaps my analysis is all wrong, even deeply flawed. But the stakes are too high to continue on the current course without reexamining the data and the erroneous models that are predicting doom.” Maybe this should have been his first paragraph, and maybe he should have omitted the word “erroneous,” as that seems to me a premature judgment. Perhaps one should be especially careful about such disclaimers in a time of emergency, especially when political leaders might be more inclined to trust the advice of someone who is generally aligned with them on policy issues.

But Epstein is, to my mind, one of the great legal thinkers of our age. And because legal scholarship aims to influence public policy, it is inherently interdisciplinary. Legal scholars, especially those who read as broadly as Epstein, should not stay in their lanes. And, to switch sports metaphors, they should swing for the fences, even if that means that they might strike out. Like other heterodox scholars, Epstein is unfraid of making controversial arguments, like his criticism of employment discrimination law. I don’t agree with that argument but think that public discourse is better when someone advances deeply thoughtful cases against propositions that almost all of us hold dear.

Hanson isn’t afraid to offend people either. He swings for the fences all the time and, however many strikeouts he may have accumulated, has hit at least three home runs in very different parts of the ballpark: first, with his groundbreaking work on prediction markets; second, in his discussion of the Great Filter in the context of the Fermi Paradox; and third, in his provocative dystopian analysis of a future world with many simulated brains. (I don’t mean to imply that I agree with all his work in these areas, but surely I can score an academic idea as a home run even without agreeing it.) It isn’t a coincidence that his greatest work is published outside of conventional academic journals.

Hanson included disclaimers too. He acknowledged that controlled exposure was a “disturbing” idea. He noted that the system might be implemented, albeit not as efficiently, through “volunteers.” He merely suggested that “authorities, and the rest of us, should at least consider controlled infection as a future option.” Disclaimers, it turns out, don’t do much to reduce internet outrage. Is Hanson right? His model seems plausible to me, but I haven’t examined it closely enough or heard enough from critics to assess. But we need creative ideas during a pandemic at least as much as during ordinary times. Time is critical in this fight, and if he and critics have given us a head start in analyzing unconventional strategies like variolation, perhaps that will help us better assess those strategies should we come to a point where people are desperate enough to consider counterintuitive approaches.

Disclosure: I know both Hanson (who was an interdepartmental colleague of mine when I was a law professor at George Mason) and Epstein (who was at University of Chicago when I visited there in 2005).

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3buOhmi

via IFTTT