We’re On The Road To Japanification

via Economic Cycle Research Institute (ECRI),

ECRI’s Lakshman Achuthan joined CNBC’s Closing Bell yesterday to discuss the cyclical outlook and the Fed.

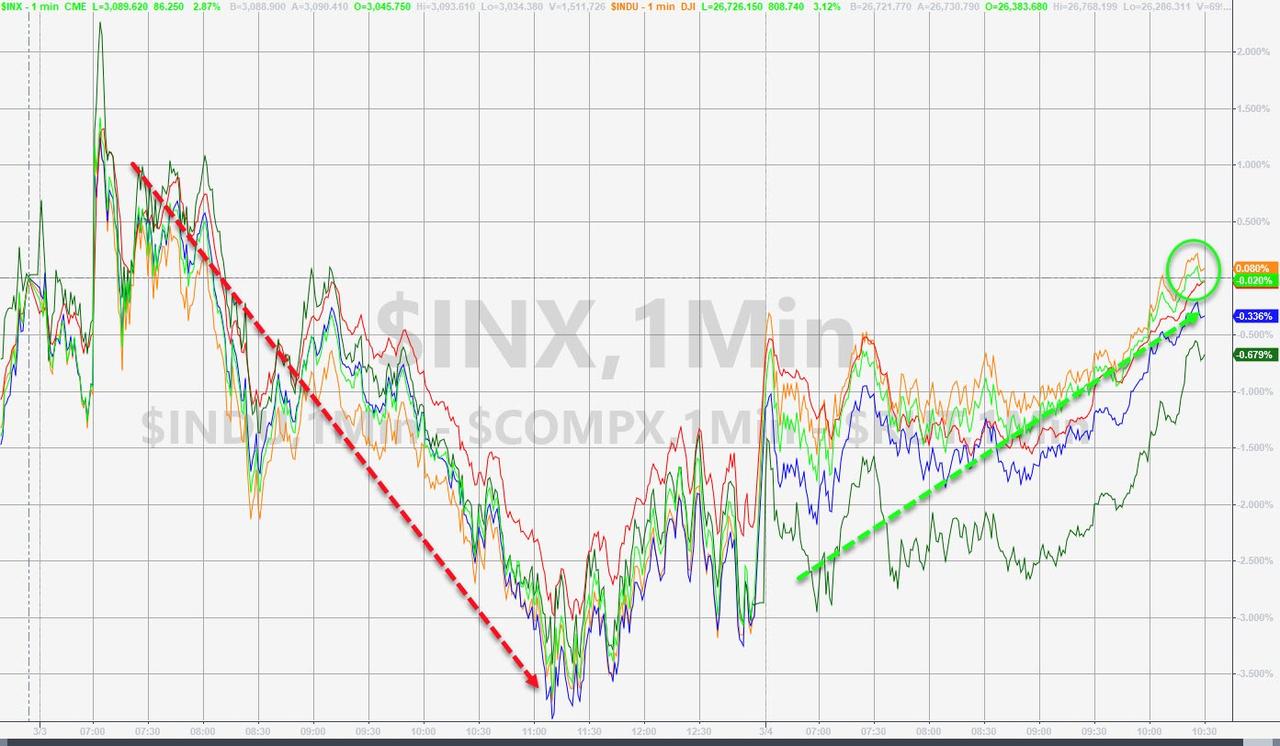

Our research shows that – predating today’s rate cut – most major western economies, including the U.S., came into this epidemic in more resilient cyclical shape than many realize.

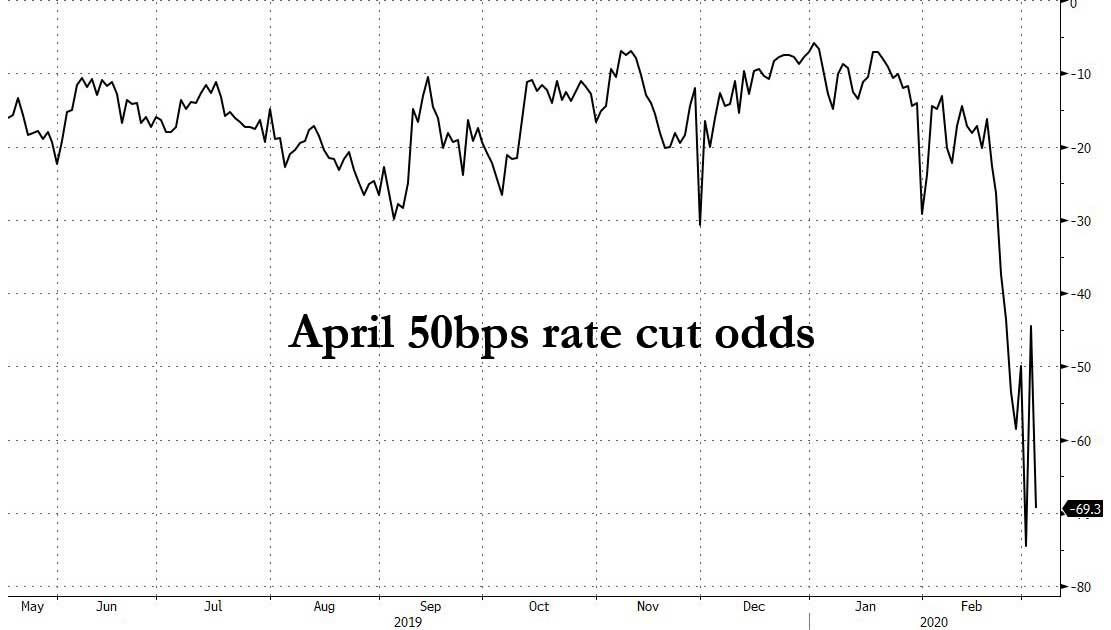

Hence, the rate cut was ill-timed.

The relevant question is whether we were headed into a recession. In answering that question – based on not just one, but more than a dozen ECRI leading indexes for the U.S. alone – our key insight is that, going into this epidemic, the economy was not in a cyclical window of vulnerability when negative shocks are actually recessionary. Despite all of the drama in the markets, the economy still isn’t in a window of vulnerability.

Within the U.S., construction was already in good cyclical shape; and while lower mortgage rates can’t hurt, they weren’t necessary to shore up the industry. And manufacturing actually went into the epidemic in a better cyclical position than most realize, and that extends beyond the U.S.

Last summer, ECRI called a Eurozone growth upturn. As of February, even with the spread of the virus, the Eurozone manufacturing PMI had risen to a one-year high. And even in the U.S. – which we knew had lagged the Eurozone in this cycle – the manufacturing PMIs are still holding above last year’s lows, despite the supply chain disruptions.

Going forward, we are keeping a close eye on all of our indexes, including several high-frequency indicators, so we will know promptly if we are moving into a recessionary window of vulnerability that would actually call for Fed action.

If we end up sidestepping a recession – not because of the Fed’s actions but because of the economy’s cyclical resilience and the efforts of medical professionals – will the Fed be able to take back those rate cuts? We are doubtful, and believe it’s now left with just two more 50-basis-point rate cuts to use when a recession really threatens.

The Fed may have intended the rate cuts to be a booster shot for the economy, but they’ve administered the wrong vaccine – because they don’t know that the economy isn’t in a recessionary window of vulnerability. So, when we really need that anti-recession vaccine, the Fed will be out of stock.

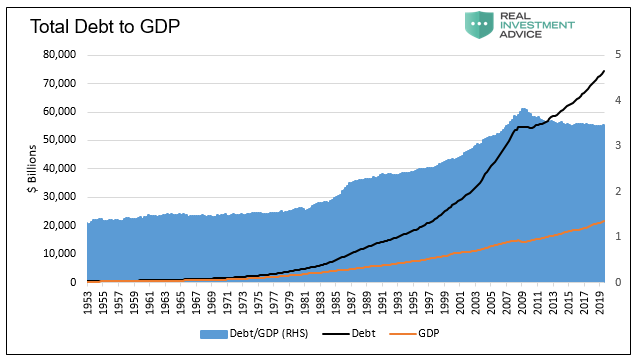

The bottom line is that the Fed’s action is far from costless. All it has done is to step on the gas on the road to Japanification.

Please note that Japan is now in its fifth recession since 2008, despite extreme monetary and fiscal policy, including Abenomics. Do we really want to go there?

* * *

Review ECRI’s recent real-time track record. For information on ECRI professional services, please contact us. Follow @businesscycle on Twitter and ECRI on LinkedIn.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 03/04/2020 – 14:45

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3cv4lWh Tyler Durden