June Payrolls Preview: It Could Go Either Way

Tyler Durden

Wed, 07/01/2020 – 22:04

Ahead of tomorrow’s June non-farm payrolls, consensus expects an increase of 3.1 million jobs, however with great uncertainty across estimates. Here is the rest of consensus expectations from tomorrow’s report:

- Nonfarm Payrolls exp. 3mln (range 405k to +9mln, prev. +2.51mln);

- Unemployment rate exp. 12.3% (range: 10.1- 15.5%%), prev. 13.3%;

- U6 unemployment prev. 21.2%; Participation prev. 60.8%;

- Private payrolls exp. +2.9mln, prev. +3.01mln;

- Manufacturing payrolls exp. 311k, prev. 225kmln;

- Government payrolls prev. -585k;

- Average earnings M/M exp. -0.7%, prev. -1.0%;

- Average earnings Y/Y exp. +5.3%, prev. +6.7%;

- Average workweek hours exp. 34.5hrs, prev. 34.7hrs.

According to Standard Chartered’s Steven Englander, dropping the top and bottom 10% of payrolls forecasts still leaves a central range of 1.65-5.00mn jobs, an extremely wide band that reflects the multiplicity of shocks hitting US labor markets.

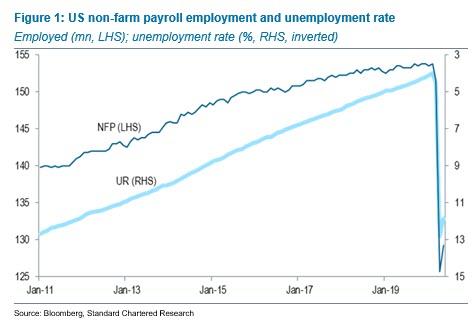

According to NewsSquawk, the March and April jobs reports saw a cumulative 22.1 million jobs shed from the US economy, and as such, analysts will be looking at the cumulative pace of recovery too; if the June consensus is realized, we will have seen around 5.5 million of those jobs return highlighting the uphill task the economy faces in ‘normalizing’.

Meanwhile, the jobless rate is seen falling to 12.3%; the Fed has projected that rate would fall to 9.3% by the end of this year, and fall further to 6.5% at the end of 2021. Analysts will pay particular attention to the participation rate, given the long-term impact participation can have on employment and wage growth levels. Heading into the data, we are deprived of some of the usual proxies we monitor to gauge the US labor market conditions; benchmark revisions diminishes the usefulness of the ADP survey, while we do not have a complete set of business surveys (notably, the services ISM will be released after the jobs report), leaving a degree of uncertainty around projections.

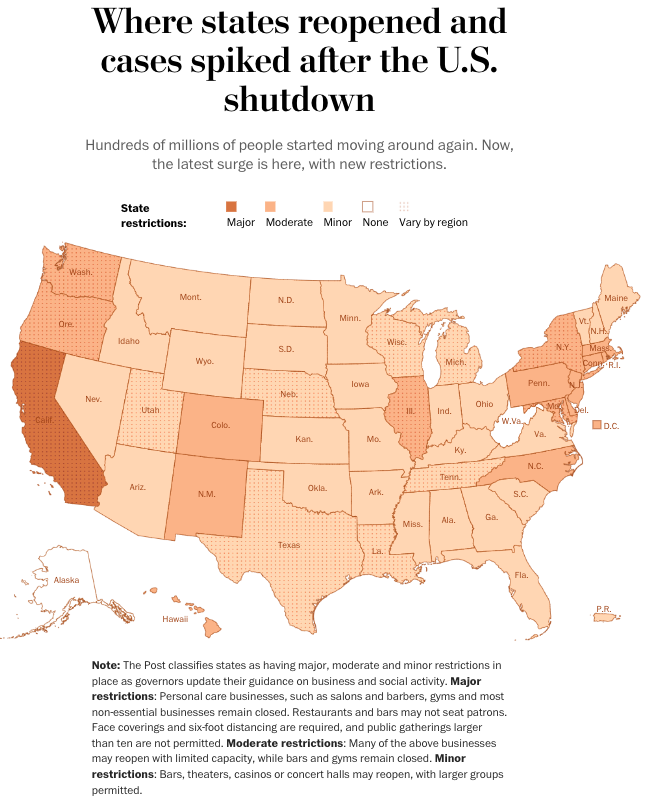

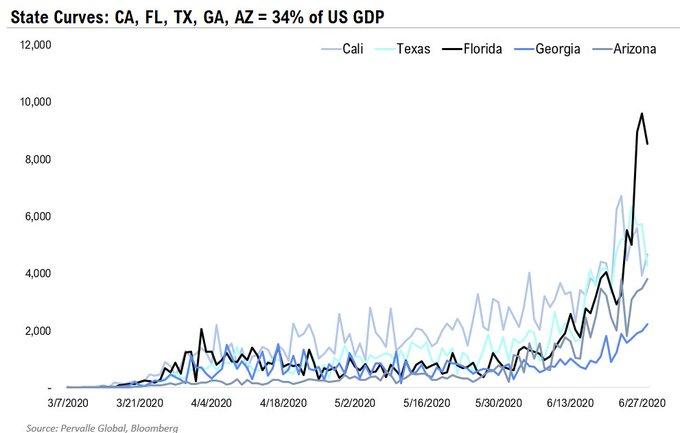

As Englander adds, the consensus for job gains reflects a drop in weekly initial unemployment claims and a clear but more modest drop in continuing unemployment claims, as well as less established mobility and restaurant reservation data. Even with COVID-19 resurgence fears, activity indicators were much higher in the June survey week than in May.

According to the strategist, given the multitude of stimulus programs in place, a weak number is unambiguously weak. The ambiguity lies in how much the job maintenance requirements of some programs induce temporary hiring. A strong number could reflect economic improvement or fiscal incentives to hire. Job losses have taken employment back to 2011 levels. The Fed worries that workers will be laid off if programs are scaled back, so it will likely maintain an aggressively stimulatory policy stance. That said, once benefits start tapering out after the month of July, a second wave of mass layoffs is widely expected unless the imminent fiscal cliff is not refreshed with trillions in new stimulus.

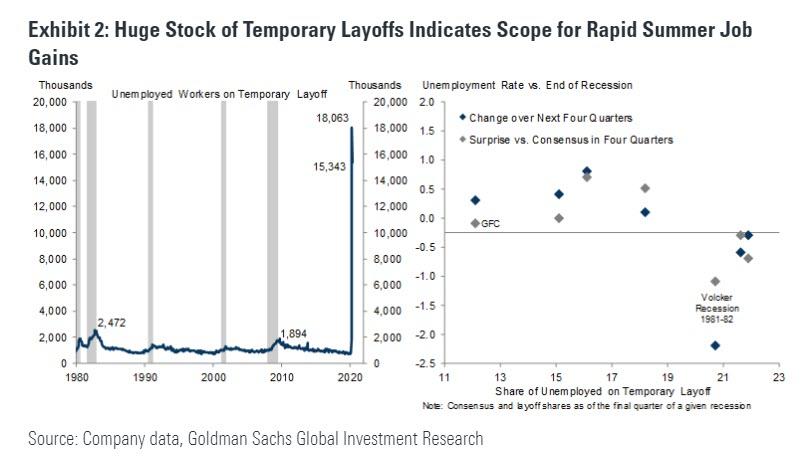

In its preview of the payrolls, report, Goldman writes that the bank will again pay special attention to the number and share of workers on temporary layoff, which spiked to a record high 18.1mn in April and remained elevated at 15.3mn in May. Over the last 50 years, the three recessions with the highest share of temporary layoffs were followed by the fastest labor market recoveries (both absolutely and relative to consensus forecasts at the time). If year-to-date job losses remain concentrated in this segment, it would increase the scope for continued rapid payroll gains this summer.

On the other hand, if the BLS fixes the “survey error” its admitted to have made in previous months which reduced the unemployment rate by up to 3%, it is possible that a far worse number could be reported tomorrow.

To this effect, Goldman also expects that about half of the 4.9mn excess workers that were employed but not at work for “other reasons” in May will be reclassified as unemployed in the June household survey, applying upward pressure on the unemployment rate. Additionally, Goldman expects the labor force participation rate increased as business reopenings encouraged job searches. Correcting for misclassification of unemployed workers, the bank estimates the “true” unemployment rate declined more significantly, but to an even higher level (-2.4% to 14.0% in June from 16.4% in May).

Below are some other considerations heading into tomorrow’s jobs report:

PARTICIPATION:

Analysts have suggested that in the current environment, the participation rate may hold more informational value than usual. That rate has declined sharply, and since March, there has been a surge in the number of people out of work but ‘not in the labor force’ (so are not looking for a job); UBS argues that they may not have looked because they believed they would be rehired; or they may not have looked because of mobility restrictions; their detachment from the labor force may prove to be temporary. “However, sustained lower-levels of labor force participation have long-running effects on employment probabilities and wages,” the bank writes, “the slow recovery in employment after the last recession was an example, and the path of labor force participation will be key to this recovery.”

INITIAL JOBLESS CLAIMS: In the week which corresponds with the BLS jobs report data, initial jobless claims again disappointed expectations. “It’s not clear why claims are still so high; is it the initial shock still working its way up through businesses away from the consumer-facing jobs lost in the first wave, or is it businesses which thought they could survive now throwing in the towel, or both?” Pantheon Macroeconomics says; either way, it argues that the numbers were disappointing, and serve to emphasize that a full recovery is going to take a long time. It is also worth noting that after the May jobs report confounded expectations, and some reason that the analyst community may have been wrong-footed by putting too much weight onto the weekly claims data, which have recently pointed at only limited improvement in labour market conditions.

ADP: The ADP’s gauge of payroll growth in June disappointed expectations, seeing 2.37mln jobs added versus the 3mln expected; the prior, however, was significantly revised up from -2.76mln to +3.07mln; Moody’s economists said that there is no information in the revisions, which was more a reflection of the benchmarking of ADP data to the official BLS data, adding that the May payrolls were significantly overstated. Indeed, other analysts explain that the ADP data is based on a model which includes lagged official BLS data, which diminishes the usefulness of the ADP data. However, there were some interesting details in the release: leisure and hospitality sectors added 961k jobs as restaurants reopened; health care added 246k jobs, and the housing sector added 394k jobs as demand firms within the market; meanwhile, manufacturing employment was subdued, adding 88k jobs, which might indicate factories are not opening up as quickly as had been hoped. Capital Economics said the data suggests some downside risk to its above-consensus forecast for a 5mln increase in nonfarm payrolls, but notes that a research paper from the Brookings Institute last week argued that the raw ADP microdata, rather than the model-based estimates the ADP publicly release, was consistent with the stronger 5mln rise.

BUSINESS SURVEYS: The ISM manufacturing report saw the employment sub-index jump 10 points to 42.1, the largest M/M increase since April 1961; it was however the eleventh straight month of employment contraction. Nevertheless, three of the six big industry sectors saw expansion as stay-athome orders were lifted, but long-term labor market growth remains uncertain, the report stated, though signs were positive given the moderately strong new order levels and a softening of backlog contraction were encouraging signs. The ISM non-manufacturing data has not been released yet (will be published on Monday), depriving us of glimpse at employment conditions in the non-manufacturing sectors of the US.

CHALLENGER JOB CUTS: Layoffs came in at 170k in June vs the prior 397k. Challenger noted the “job cuts are trending down, as expected, as businesses begin the difficult task of reopening. However, with a resurgence in cases, millions of Americans out of work, and enhanced unemployment benefits coming to an end soon, we may expect more companies to make cuts as consumer and business spending slows.” Of the job cuts this year, COVID has been the main cause, while market conditions and demand downturn have also been cited; both knock-on effects of COVID. The fall in oil prices was cited as the reason behind some of the job losses this year, it adds. The majority of the job cuts in June comes from Entertainment/Leisure companies, retailers were second, services sector third, followed by the automotive sector.

Arguing for a better-than-consensus report:

- Big Data. Alternative datasets generally validate this message, with sizeable increases in mobility data from Google and Homebase and an 8% increase in the employment ratio in the Dallas Fed’s Real Time Population Survey.

- Seasonality. There should be a seasonal bias in education categories to boost job growth by roughly 0.5mn, as some of the janitors and other school staff who normally finish the school year in May and June stopped work in April.

- Job availability. The Conference Board labor differential—the difference between the percent of respondents saying jobs are plentiful and those saying jobs are hard to get—rebounded meaningfully to -3.0 from -12.7 in May and -15.7 in April (but remains in contractionary territory).

- Employer surveys. Business activity surveys improved on net in June but generally remained in near contractionary territory, and the employment components of Goldman’s survey trackers rebounded somewhat less sharply (non-manufacturing +5.2 to 37.6; manufacturing +5.1 to 43.8).

Arguing for a worse-than-consensus report:

- Jobless claims. While initial jobless claims indicate that layoffs proceeded at an elevated pace (averaging 1.8mn per week), continued claims declined by 1.3mn from survey week to survey week. Furthermore, the decline in continuing claims likely understates the pace of job growth because underemployed part-time workers are still generally eligible for benefits (and the $600 benefit top-up increases the incentive to continue to file).

- Census hiring. Census temporary workers are set to decline by 4k in June due to the coronavirus.

Neutral factors:

- ADP. Private sector employment in the ADP report rose by 2,369k in June. While below expectations, the implications of the miss for are clouded by large swings in the statistical inputs to the ADP model this month, in our view. Our main takeaway from the report was the upbeat remarks in the report itself, which presumably is a reflection of the underlying ADP data.

- Job cuts. Announced layoffs reported by Challenger, Gray & Christmas pulled back 51% in June to 182k after falling 45% in May and rising 266% in April. Despite the decline, they remain 304% above their June 2019 levels.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2YTduU6 Tyler Durden