Authored by Pepe Escobar via The Asia Times,

Moscow is painfully aware that the US/NATO “strategy” of containment of Russia is already reaching fever pitch. Again.

This past Wednesday, at a very important meeting with the Federal Security Service board, President Putin laid it all out in stark terms:

We are up against the so-called policy of containing Russia. This is not about competition, which is a natural thing for international relations. This is about a consistent and quite aggressive policy aimed at disrupting our development, slowing it down, creating problems along the outer perimeter, triggering domestic instability, undermining the values that unite Russian society, and ultimately to weaken Russia and put it under external control, just the way we are witnessing it transpire in some countries in the post-Soviet space.

Russian President Vladimir Putin during a meeting of the Federal Security Service Board in Moscow on February 24. Photo: AFP / Alexei Druzhinin / Sputnik

Not without a touch of wickedness, Putin added this was no exaggeration: “In fact, you don’t need to be convinced of this as you yourselves know it perfectly well, perhaps even better than anybody else.”

The Kremlin is very much aware “containment” of Russia focuses on its perimeter: Ukraine, Georgia and Central Asia. And the ultimate target remains regime change.

Putin’s remarks may also be interpreted as an indirect answer to a section of President Biden’s speech at the Munich Security Conference.

According to Biden’s scriptwriters,

Putin seeks to weaken the European project and the NATO alliance because it is much easier for the Kremlin to intimidate individual countries than to negotiate with the united transatlantic community … The Russian authorities want others to think that our system is just as corrupt or even more corrupt.

US President Joe Biden speaks virtually from the East Room of the White House in Washington, DC, to the Munich Security Conference in Germany on February 19. Photo: AFP / Mandel Ngan

A clumsy, direct personal attack against the head of state of a major nuclear power does not exactly qualify as sophisticated diplomacy. At least it glaringly shows how trust between Washington and Moscow is now reduced to less than zero. As much as Biden’s Deep State handlers refuse to see Putin as a worthy negotiating partner, the Kremlin and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs have already dismissed Washington as “non-agreement capable.”

Once again, this is all about sovereignty. The “unfriendly attitude towards Russia,” as Putin defined it, extends to “other independent, sovereign centers of global development.” Read it as mainly China and Iran. All these three sovereign states happen to be categorized as top “threats” by the US National Security Strategy.

Yet Russia is the real nightmare for the Exceptionalists: Orthodox Christian, thus appealing to swaths of the West; consolidated as major Eurasian power; a military, hypersonic superpower; and boasting unrivaled diplomatic skills, appreciated all across the Global South.

In contrast, there’s not much left for the deep state except endlessly demonizing both Russia and China to justify a Western military build-up, the “logic” inbuilt in a new strategic concept named NATO 2030: United for a New Era.

The experts behind the concept hailed it as an “implicit” response to French President Emmanuel Macron’s declaring NATO “brain dead.”

Well, at least the concept proves Macron was right.

Those barbarians from the East

Crucial questions about sovereignty and Russian identity have been a recurrent theme in Moscow these past few weeks. And that brings us to February 17, when Putin met with Duma political leaders, from the Communist Party’s Vladimir Zhirinovsky – enjoying a new popularity surge – to United Russia’s Sergei Mironov, as well as State Duma speaker Vyacheslav Volodin.

Putin stressed the “multi-ethnic and multi-religious” character of Russia, now in “a different environment that is free of ideology”:

It is important for all ethnic groups, even the smallest ones, to know that this is their Motherland with no other for them, that they are protected here and are prepared to lay down their lives in order to protect this country. This is in the interests of us all, regardless of ethnicity, including the Russian people.

Yet Putin’s most extraordinary remark had to do with ancient Russian history:

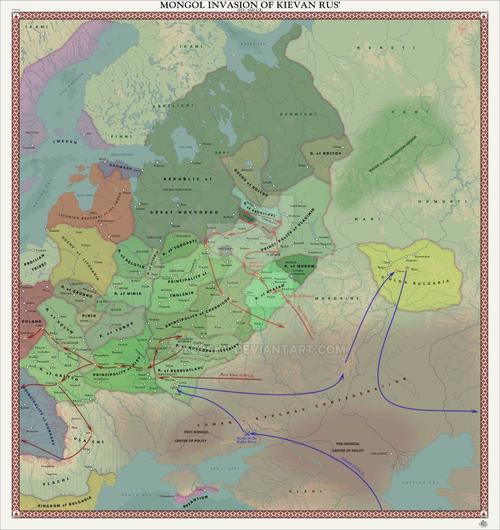

Barbarians came from the East and destroyed the Christian Orthodox empire. But before the barbarians from the East, as you well know, the crusaders came from the West and weakened this Orthodox Christian empire, and only then were the last blows dealt, and it was conquered. This is what happened … We must remember these historical events and never forget them.

Well, this could be enough material to generate a 1,000-page treatise. Instead, let’s try, at least, to – concisely – unpack it.

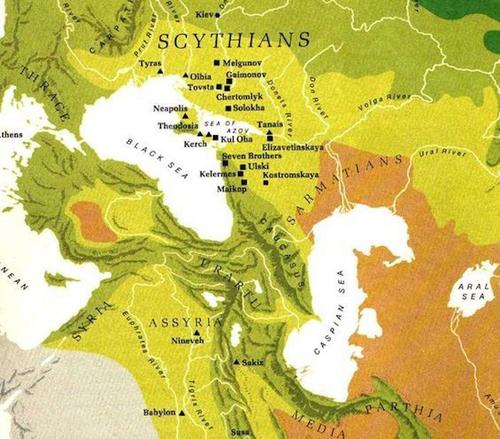

The Great Eurasian Steppe – one of the largest geographical formations on the planet – stretches from the lower Danube all the way to the Yellow River. The running joke across Eurasia is that “Keep Walking” can be performed back to back. For most of recorded history this has been Nomad Central: tribe upon tribe raiding at the margins, or sometimes at the hubs of the heartland: China, Iran, the Mediterranean.

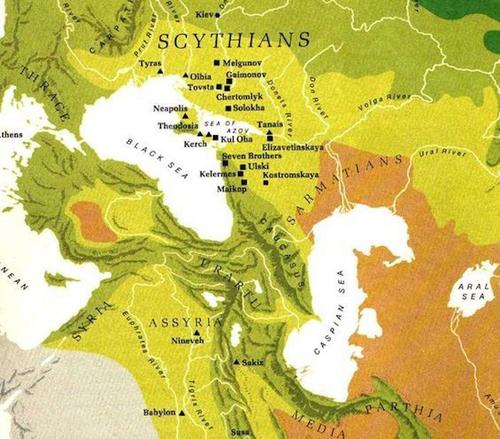

The Scythians (see, for instance, the magisterial The Scythians: Nomad Warriors of the Steppe, by Barry Cunliffe) arrived at the Pontic steppe from beyond the Volga. After the Scythians, it was the turn of the Sarmatians to show up in South Russia.

From the 4th century onward, nomad Eurasia was a vortex of marauding tribes, featuring, among others, the Huns in the 4th and 5th centuries, the Khazars in the 7th century, the Kumans in the 11th century, all the way to the Mongol avalanche in the 13th century.

The plot line always pitted nomads against peasants. Nomads ruled – and exacted tribute. G Vernadsky, in his invaluable Ancient Russia, shows how “the Scythian Empire may be described sociologically as a domination of the nomadic horde over neighboring tribes of agriculturists.”

As part of my multi-pronged research on nomad empires for a future volume, I call them Badass Barbarians on Horseback. The stars of the show include, in Europe, in chronological order, Cimmerians, Scythians, Sarmatians, Huns, Khazars, Hungarians, Peshenegs, Seljuks, Mongols and their Tatar descendants; and, in Asia, Hu, Xiongnu, Hephtalites, Turks, Uighurs, Tibetans, Kirghiz, Khitan, Mongols, Turks (again), Uzbeks and Manchu.

Arguably, since the hegemonic Scythian era (the first protagonists of the Silk Road), most of the peasants in southern and central Russia were Slav. But there were major differences. The Slavs west of Kiev were under the influence of Germania and Rome. East of Kiev, they were influenced by Persian civilization.

It’s always important to remember that the Vikings were still nomads when they became rulers in Slav lands. Their civilization in fact prevailed over sedentary peasants – even as they absorbed many of their customs.

Interestingly enough, the gap between steppe nomads and agriculture in proto-Russia was not as steep as between intensive agriculture in China and the interlocked steppe economy in Mongolia.

(For an engaging Marxist interpretation of nomadism, see A N Khazanov’s Nomads and the Outside World).

The sheltering sky

What about power? For Turk and Mongol nomads, who came centuries after the Scythians, power emanated from the sky. The Khan ruled by authority of the “Eternal Sky” – as we all see when we delve into the adventures of Genghis and Kublai. By implication, as there is only one sky, the Khan would have to exert universal power. Welcome to the idea of universal empire.

Kublai Khan as the first Yuan emperor, Shizu. Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). Album leaf, ink and color on silk. National Palace Museum, Taipei. Photo: Wikimedia Commons/National Palace Museum, Taipei

In Persia, things were slightly more complex. The Persian Empire was all about Sun worship: that became the conceptual basis for the divine right of the King of Kings. The implications were immense, as the King now became sacred. This model influenced Byzantium – which, after all, was always interacting with Persia.

Christianity made the Kingdom of Heaven more important than ruling over the temporal domain. Still, the idea of Universal Empire persisted, incarnated in the concept of Pantocrator: it was the Christ who ultimately ruled, and his deputy on earth was the Emperor. But Byzantium remained a very special case: the Emperor could never be an equal to God. After all, he was human.

Putin is certainly very much aware that the Russian case is extremely complex. Russia essentially is on the margins of three civilizations. It’s part of Europe – reasons including everything from the ethnic origin of Slavs to achievements in history, music and literature.

Russia is also part of Byzantium from a religious and artistic angle (but not part of the subsequent Ottoman empire, with which it was in military competition). And Russia was influenced by Islam coming from Persia.

Then there’s the crucial influence of nomads. A serious case can be made that they have been neglected by scholars. The Mongol rule for a century and a half, of course, is part of the official historiography – but perhaps not given its due importance. And the nomads in southern and central Russia two millennia ago were never properly acknowledged.

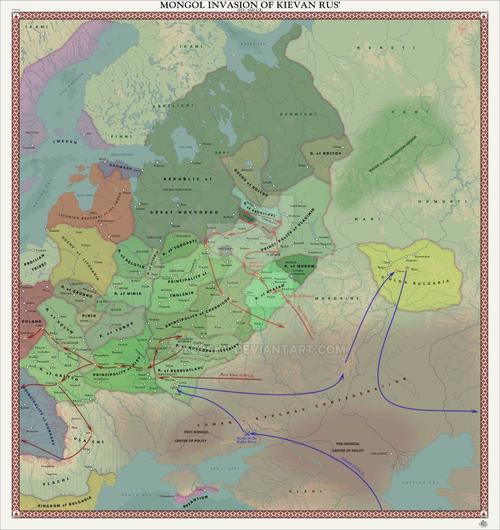

So Putin may have hit a nerve. What he said points to the idealization of a later period of Russian history from the late 9th to early 13th century: Kievan Rus. In Russia, 19th century Romanticism and 20th century nationalism actively built an idealized national identity.

The interpretation of Kievan Rus poses tremendous problems – that’s something I eagerly discussed in St. Petersburg a few years ago. There are rare literary sources – and they concentrate mostly on the 12th century afterwards. The earlier sources are foreigners, mostly Persians and Arabs.

Russian conversion to Christianity and its concomitant superb architecture have been interpreted as evidence of a high cultural standard. In a nutshell, scholars ended up using Western Europe as the model for the reconstruction of Kievan Rus civilization.

It was never so simple. A good example is the discrepancy between Novgorod and Kiev. Novgorod was closer to the Baltic than the Black Sea, and had closer interaction with Scandinavia and the Hanseatic towns. Compare it with Kiev, which was closer to steppe nomads and Byzantium – not to mention Islam.

Kievan Rus was a fascinating crossover. Nomadic tribal traditions – on administration, taxes, the justice system – were prevalent. But on religion, they imitated Byzantium. It’s also relevant that until the end of the 12th century, assorted steppe nomads were a constant “threat” to southeast Kievan Rus.

So as much as Byzantium – and, later on, even the Ottoman Empire – supplied models for Russian institutions, the fact is the nomads, starting with the Scythians, influenced the economy, the social system and most of all, the military approach.

Watch the Khan

Sima Qian, the master Chinese historian, has shown how the Khan had two “kings,” who each had two generals, and thus in succession, all the way to commanders of a hundred, a thousand and ten thousand men. This is essentially the same system used for a millennia and a half by nomads, from the Scythians to the Mongols, all the way to Tamerlane’s army at the end of the 14th century.

The Mongol invasions – 1221 and then 1239-1243 – were indeed the major game-changer. As master analyst Sergei Karaganov told me in his office in late 2018, they influenced Russian society for centuries afterwards.

For over 200 years Russian princes had to visit the Mongol headquarters in the Volga to pay tribute. One scholarly strand has qualified it as “barbarization”; that seems to be Putin’s view. According to that strand, the incorporation of Mongol values may have “reversed” Russian society to what it was before the first drive to adopt Christianity.

The inescapable conclusion is that when Muscovy emerged in the late 15th century as the dominant power in Russia, it was essentially the successor of the Mongols.

And because of that the peasantry – the sedentary population – were not touched by “civilization” (time to re-read Tolstoy?). Nomad Power and values, as strong as they were, survived Mongol rule for centuries.

Well, if a moral can be derived from our short parable, it’s not exactly a good idea for “civilized” NATO to pick a fight with the – lateral – heirs of the Great Khan.