Back in December, SocGen’s resident market skeptic Albert Edwards shared with the world why he is starting to panic about soaring food prices. And since that was before food prices really took amid broken supply chains, trillions in fiscal stimulus and exploding commodity costs, off we can only imagine the sheer terror he must feel today.

A United Nations index of world food costs climbed for a 12th straight month in May, its longest stretch in a decade, rising to the highest in almost a decade, heightening concerns over bulging grocery bills.

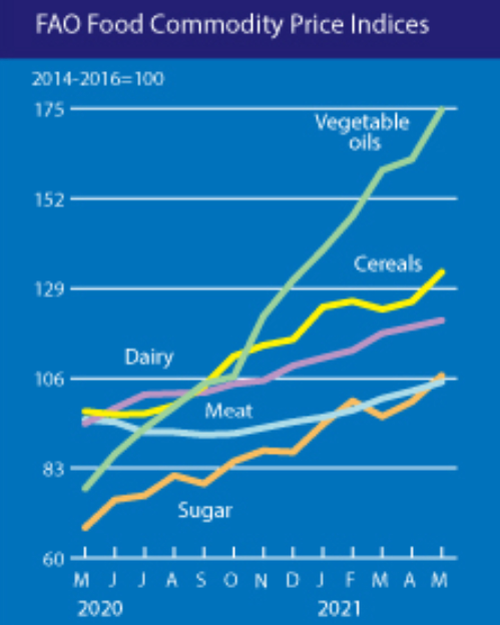

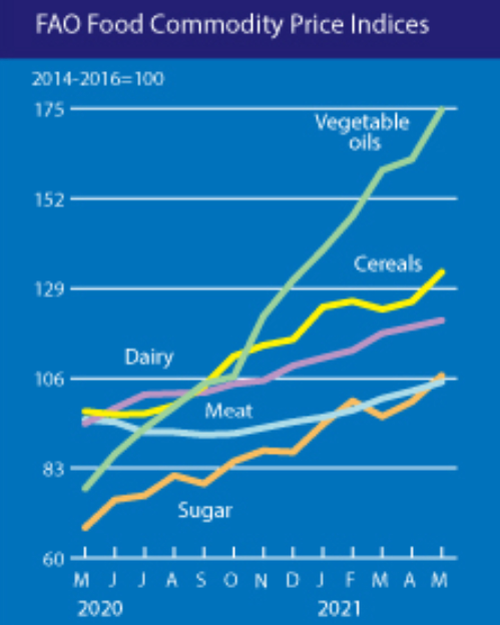

All five components of the index rose during the month, with the advance led by pricier vegetable oils, grain and sugar.

Month after month, the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization’s food price index continues to soar to levels not seen in a decade. Soaring food prices have tremendous implications on societal trends and may result in unrest in emerging market countries if trends persist.

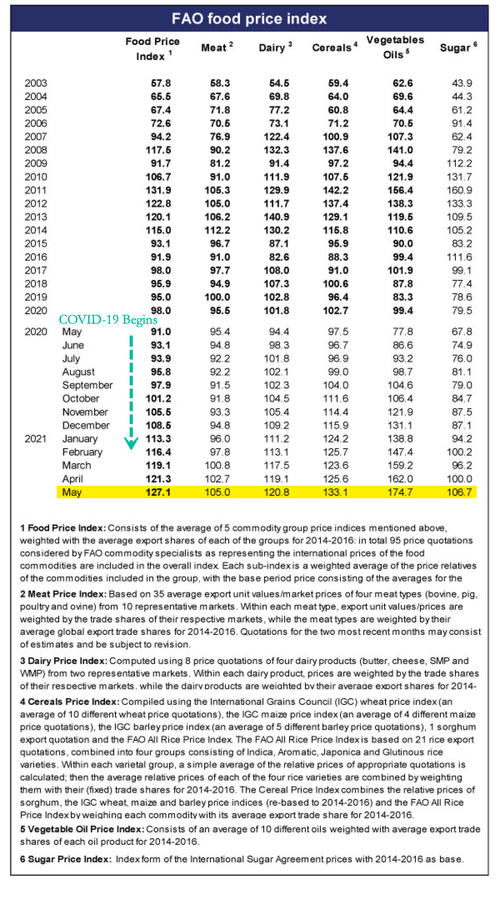

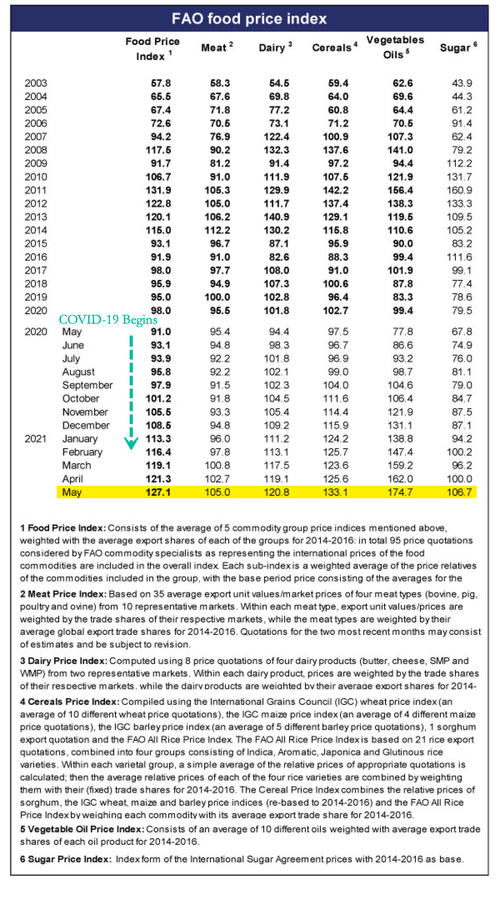

For May, the FAO Food Price Index, which measures monthly changes for a basket of cereals, oilseeds, dairy products, meat, and sugar, surged to an average of 127.1 points in May, 4.8% higher than in April and 39.7% higher than in May 2020.

The Rome-based FAO data said prices of vegetable oils, sugar, and cereals drove the increase in the overall index to the highest level not seen since September 2011 and only 7.6% below its all-time high in nominal terms.

FAO’s cereal price index rose 6.0% in May over last month and 36.6% year-on-year. Maize, also known as corn, is a cereal grain that led the surge and is up 89% over the previous year’s value. Wheat prices also saw a jump, up 6.8% in May over the prior month, while rice prices were flat.

The FAO Vegetable Oil Price Index rose 7.8% in May over the prior month, mainly reflecting rising palm, soy, and rapeseed oil prices. Palm oil prices were supported by sluggish production growth in southeast Asia, while prospects of strong global demand. Soyoil prices increased due mainly to the rising demand for biodiesel.

The FAO Sugar Price Index posted a 6.8% month-on-month gain due to harvest concerns and a decline in crop yields in Brazil.

The FAO Meat Price Index inched higher for the month, up 2.2% versus April prices, due mainly to increased import purchases by China.

The FAO Dairy Price Index rose by 1.8% on the month, up 28% from the same period last year.

Soaring international food prices began on the onset of the virus pandemic in early 2020.

This is a massive problem since food is a significant component of CPI baskets in Asia, and this inflationary impulse will strain households in these emerging markets.

The continued advance risks accelerating broader inflation, complicating central banks efforts to provide more stimulus. It also risks giving Albert Edwards terrifying nightmares.

“We have very little room for any production shock. We have very little room for any unexpected surge in demand in any country,” Abdolreza Abbassian, senior economist at the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, said by phone.

“Any of those things could push prices up further than they are now, and then we could start getting worried.”

Besides the usual factors listed above, food prices have also surged as a result of drought in key Brazilian growing regions which has crippled crops from corn to coffee, and vegetable oil production growth has slowed in Southeast Asia. That’s boosting costs for livestock producers and risks further straining global grain stockpiles that have been depleted by soaring Chinese demand. The explosive move has stirred memories of 2008 and 2011, when price spikes led to food riots in more than 30 nations and lead to a wave of violent revolutions across Northern Africa and the Middle East.

Meanwhile, as central bankers across the globe vow higher prices are “transitory”, the prolonged gains across the staple commodities have trickled through to store shelves, with countries from Kenya to Mexico reporting sharply higher food costs. The pain will be particularly pronounced in some of the poorest import-dependent nations, which have limited purchasing power and social safety nets as they grapple with the pandemic.

As Bloomberg adds, the world’s hunger problem “has already reached its worst in years as the pandemic exacerbates food inequalities, compounding extreme weather and political conflicts.”

Should violence break out as starving people take to the streets, they can thank not only the Fed but also China, as food price gains in the past year have been fueled by China’s “unpredictably huge” purchases of foreign grain, and world reserves could hold relatively flat in the coming season, Abbassian said. Summer weather across the Northern Hemisphere will be crucial to determine if U.S. and European harvests can make up for crop shortfalls elsewhere.

“We have very little room for any production shock. We have very little room for any unexpected surge in demand in any country,” Abbassian said by phone.

“Any of those things could push prices up further than they are now, and then we could start getting worried.”

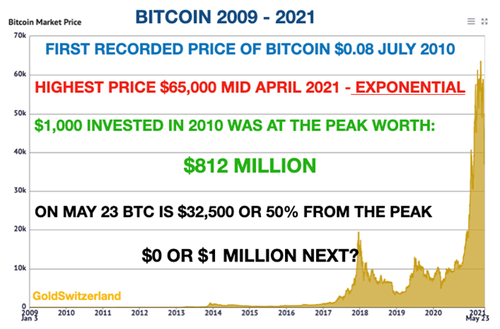

Indeed, “getting worried” is the right approach since, as you’ll notice from the chart below, the last big surge from the middle of 2010 to early 2011 coincided with the start of the Arab Spring, for which food inflation is regarded as a contributing factor.

DB’s Jim Reid reminds us that emerging markets are more vulnerable to this trend since their consumers spend a far greater share of their income on food than those in the developed world.

… and soaring food prices isn’t just an emerging market story. It’s also one for developed countries, such as the US. With millions still on pandemic unemployment insurance and the labor market in tatters, disposable personal incomes on food will have to be adjusted higher – straining the ability for people to service bills as they need to eat.

The UN’s Abbassian offered some silver lining amid the fear, saying that “we are not in the situation we were back in 2008-10 when inventories were really low and a lot of things were going on… However, we are in sort of a borderline. It’s a borderline that needs to be monitored very closely over the next few weeks, because weather is either going to really make it or create really big problems.”

We’ll see if it is “just the weather” and it’s “just transitory”…