On September 4, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) halted residential evictions in the United States for nonpayment of rent due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Many states and municipalities got there first, imposing at least partial eviction moratoriums starting in March and April of 2020. The theory behind these emergency orders was that if Americans were forced to leave their homes and move into more crowded settings, it would increase transmission of COVID-19.

The federal ban was supposed to expire at the end of 2020. Then it was extended a month, then two more months, then through the end of June, and then last week, the CDC extended it again until the end of July. Many states and cities have also extended their moratoriums—in some cases through the end of September, even as COVID-19 infection and death rates are plummeting.

Were the eviction bans necessary to protect public health during the pandemic? Two studies that got widespread media attention, and that have been cited by the federal government to support its policies, claim to show that the moratoriums saved thousands of lives.

“Researchers estimated that the lifting of moratoriums could have resulted in between 365,200 and 502,200 excess coronavirus cases and between 8,900 and 12,500 excess deaths,” noted NPR, in an interview with postdoctoral researcher Kathryn Leifheit of UCLA’s Fielding School of Public Health.

Leifheit was the lead author of “Expiring Eviction Moratoriums and COVID-19 Incidence and Mortality,” a study cited by the CDC in its order extending the federal moratorium. (Leifheit didn’t respond to our interview request, which mentioned that Reason was working with a statistician to review her results.)

The second study, which also makes dramatic claims about the eviction moratoriums, was authored by a team of researchers at Duke University. It got widespread media attention and was cited twice by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) in the federal register as justification for its rulemaking.

These studies are deeply flawed. Their underlying data are incomplete and inconsistent. Their results are implausible. The size of the effect is wildly disproportionate to other public health interventions. The researchers also claim an absurd amount of certainty in their results despite the large uncertainties in the data they use, and they assert a causal effect based solely on correlation.

If the authors were correct, they would have arrived at one of the greatest public health discoveries in history. It took over a year and perhaps $100 billion to reduce COVID-19 rates by 40 percent with vaccinations; the Duke researchers claim that if a universal eviction moratorium had been implemented six months earlier, it could have reduced death rates by over 40 percent. Researchers have struggled to demonstrate the benefits of masks, social distancing, and lockdowns with high levels of certainty. Yet these eviction moratorium researchers find high confidence for a gigantic immediate effect from a legal change affecting a tiny subset of the population.

Finally, the authors of the Duke study declined to share their dataset with Reason for scrutiny on the grounds that it hasn’t yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal, which not only raises additional red flags but is a violation of basic research ethics—particularly in the case of a study that’s been widely reported on in the media and is cited by a government agency as justification for federal policies.

Plausible Assumptions

Before delving into the statistical problems with these two studies, it will be helpful to map out plausible assumptions about the impact of the temporary eviction bans. The first step in any study, before building detailed models and making complex calculations, is to take a simple look at the aggregate picture and apply common sense. If your later rigorous analysis confirms the simple picture, you have more confidence in it. If it contradicts the simple picture, then you drill down to explain why.

In March 2020, Congress ordered a nationwide ban on evictions in federally subsidized housing for nonpayment of rent, and many states and localities added their own moratoriums that were often broader than the federal rules. That temporary federal ban expired in late July 2020, but the CDC imposed a new nationwide ban for all residential properties at the beginning of September.

There are major data challenges in assessing the effects of these rules. There is no useful aggregated reporting on evictions. We have some data on eviction filings, but one-third of jurisdictions don’t report, and reporting for the other two-thirds is often erratic. Even the hundreds of local COVID-19 temporary eviction bans are difficult to classify because they take different approaches with different terms and restrictions.

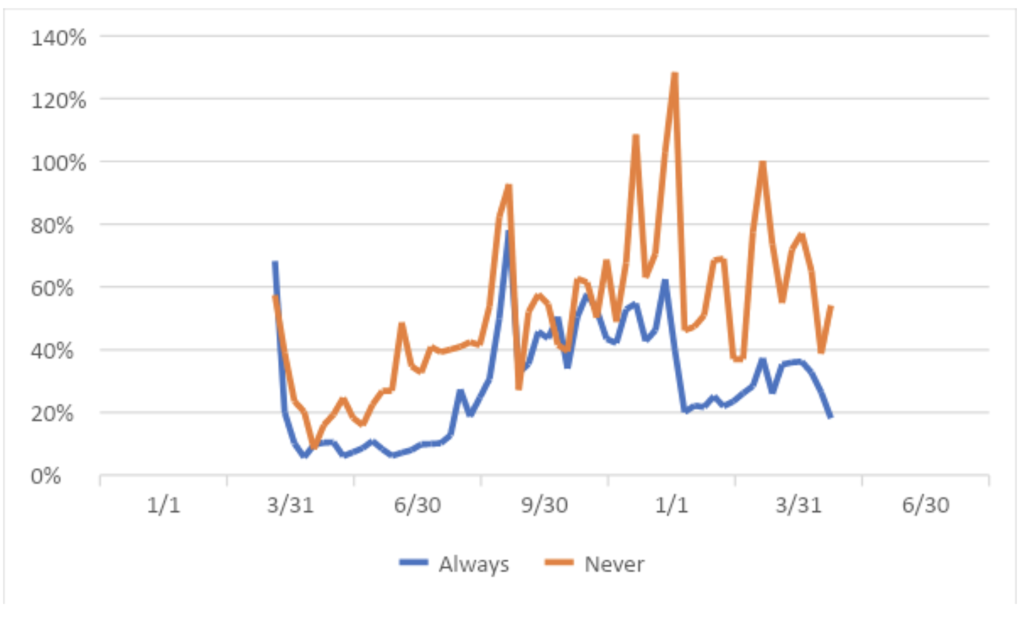

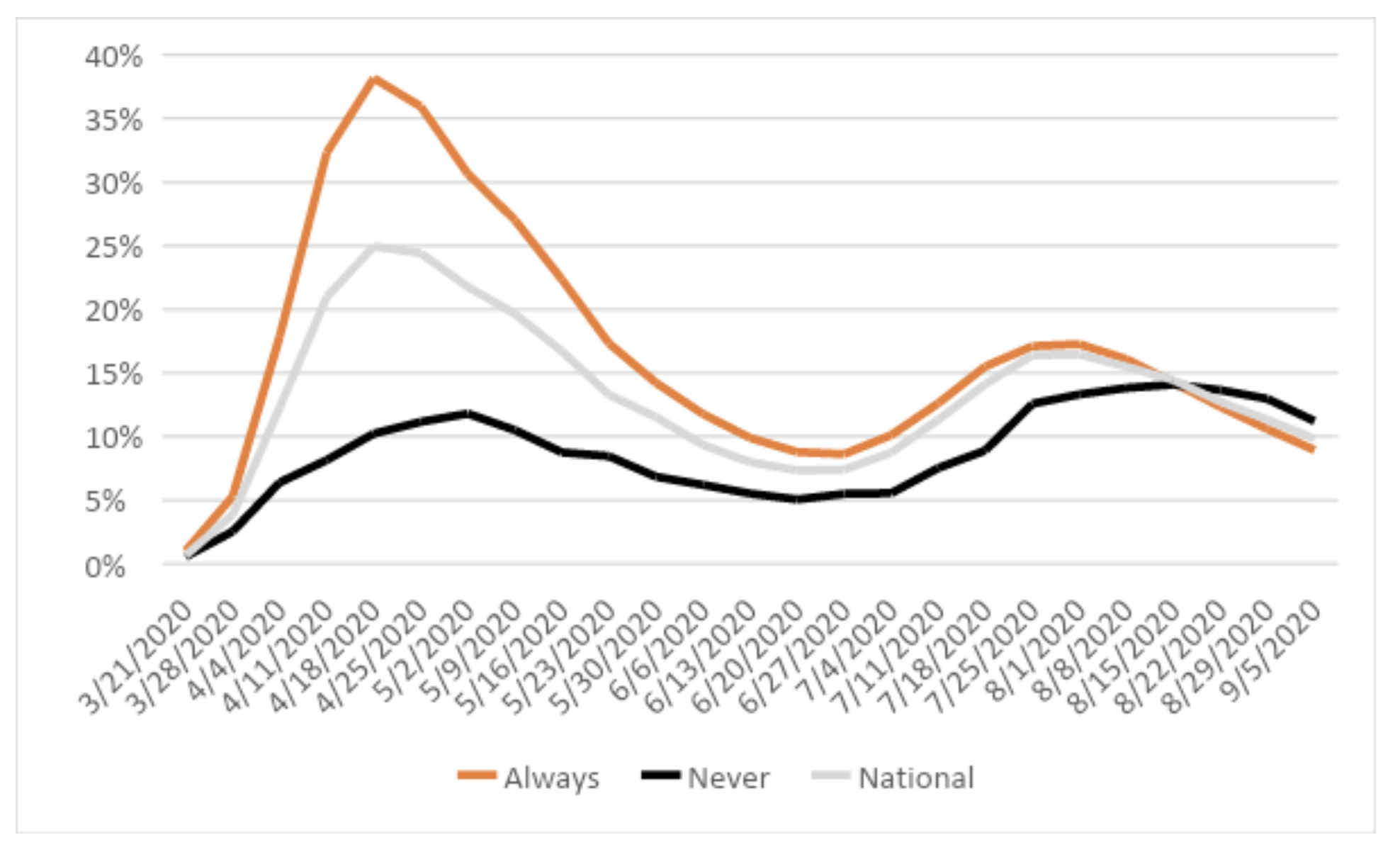

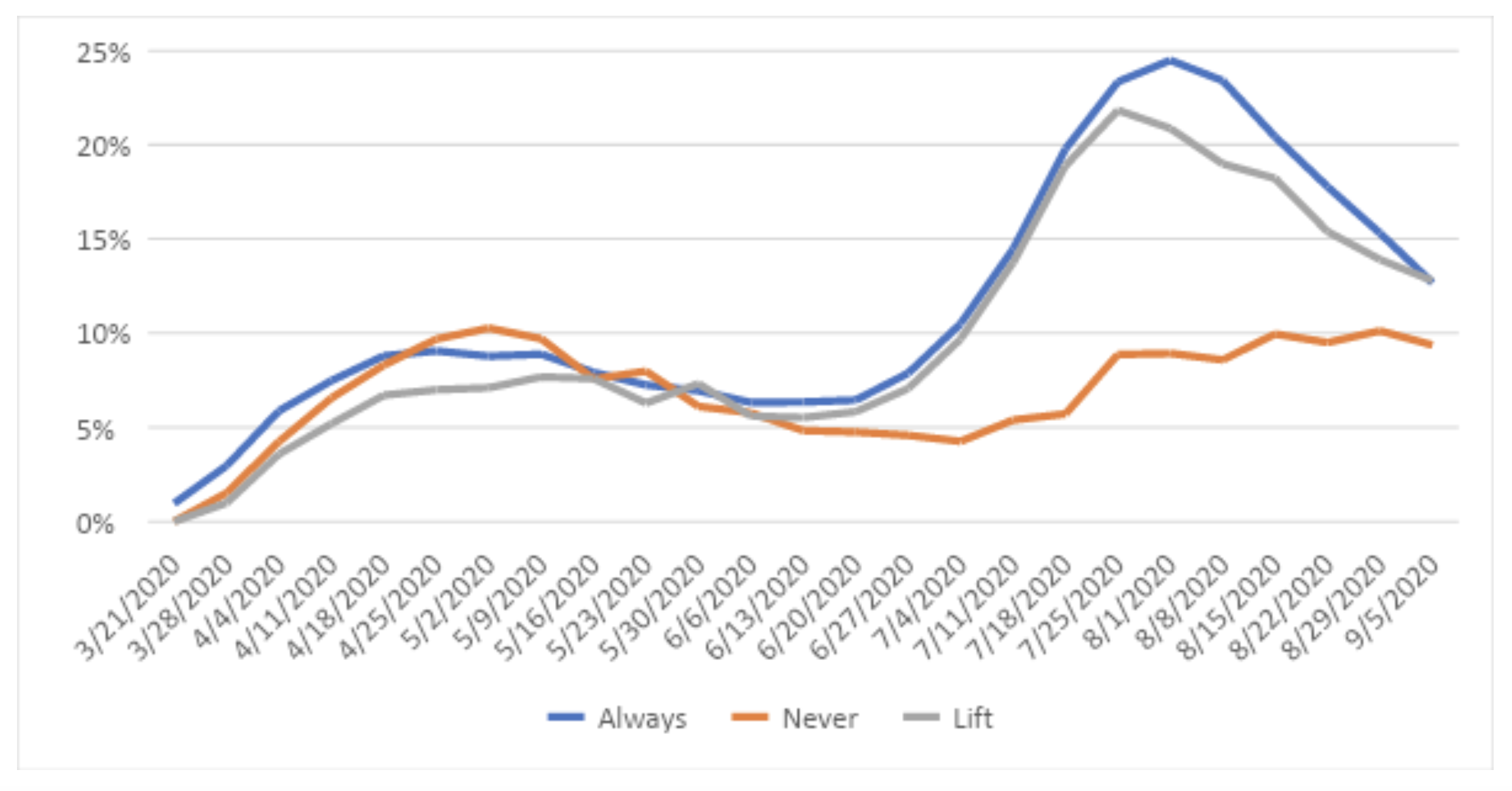

It’s nevertheless a useful exercise to throw together the data that we do have. The chart below, which is derived from data provided by the Eviction Lab at Princeton University and includes 28 locations in 17 states, shows eviction filings in 2020 and 2021 as a percentage of average filings for the same calendar week for the same jurisdiction over previous years. The blue line (“always”) is for places that had eviction moratoriums in place for the entire period and the orange line (“never”) is for places that had no local moratoriums (although, of course, the federal moratorium did apply to these localities).

The data show eviction filings plunging to near-zero levels in March and April of 2020. But starting in late April, places without statewide temporary bans gradually increased filings to about 40 percent of previous levels. Places with moratoriums also saw filings increase, but with roughly a two-month lag. In both types of places, there was a spike just before the CDC’s emergency order went into effect.

The data show eviction filings plunging to near-zero levels in March and April of 2020. But starting in late April, places without statewide temporary bans gradually increased filings to about 40 percent of previous levels. Places with moratoriums also saw filings increase, but with roughly a two-month lag. In both types of places, there was a spike just before the CDC’s emergency order went into effect.

For the first two months of the federal moratorium, both types of places ran eviction filings at about half the level of previous years. Late in 2020, we saw places that did not have moratoriums in place over the summer increase filings to something like 70 percent of previous levels, while places that had summer moratoriums dropped to around 30 percent.

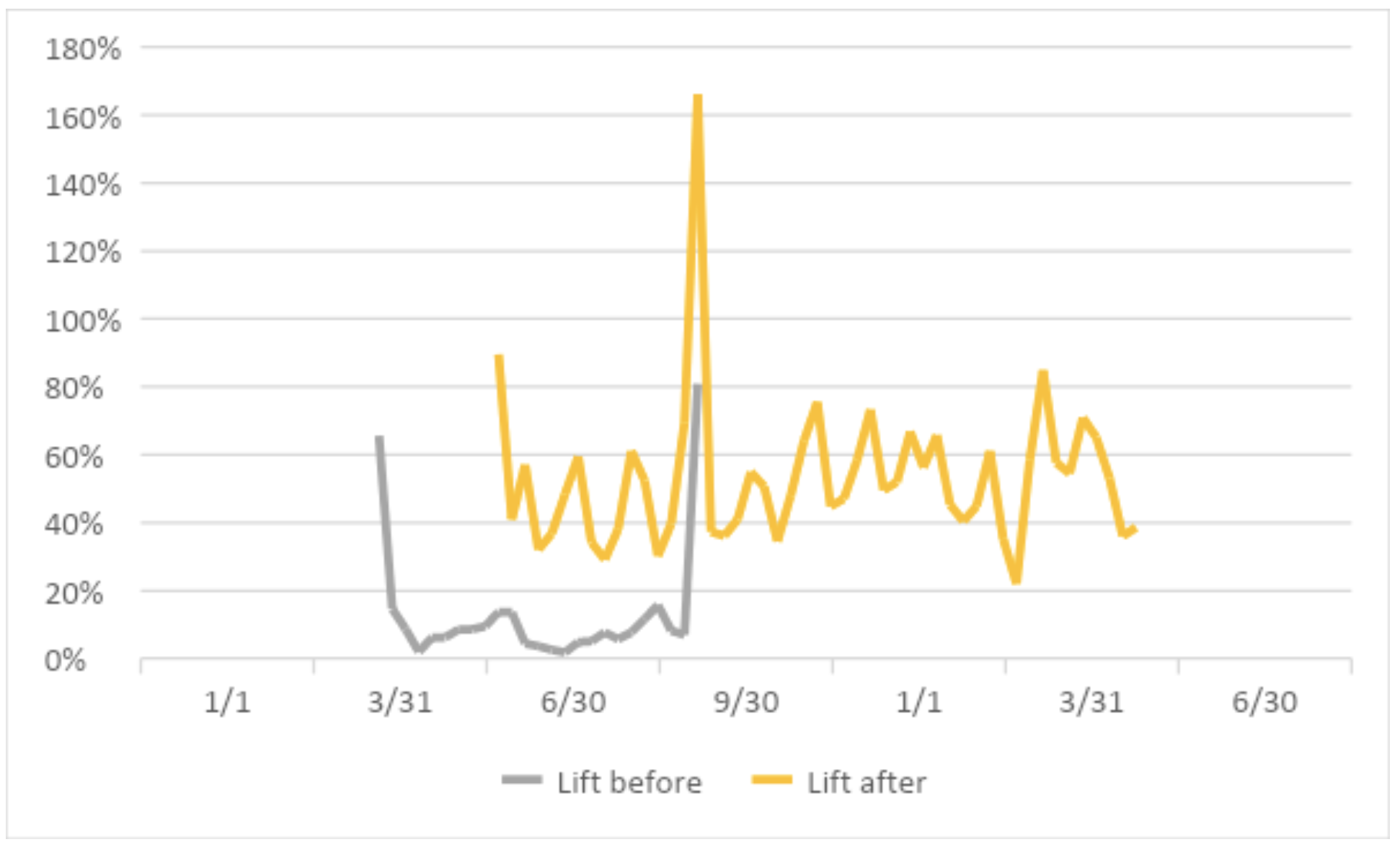

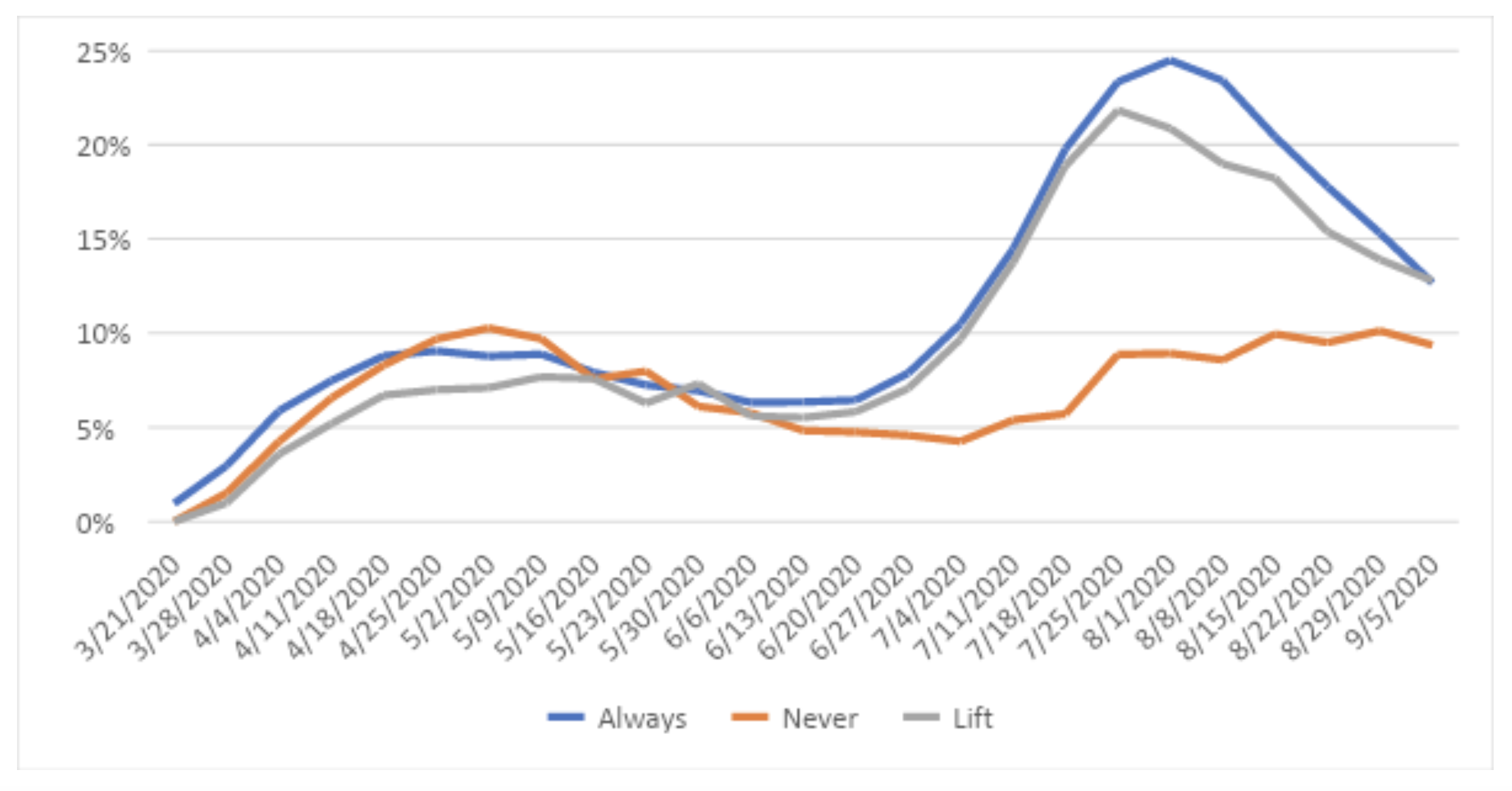

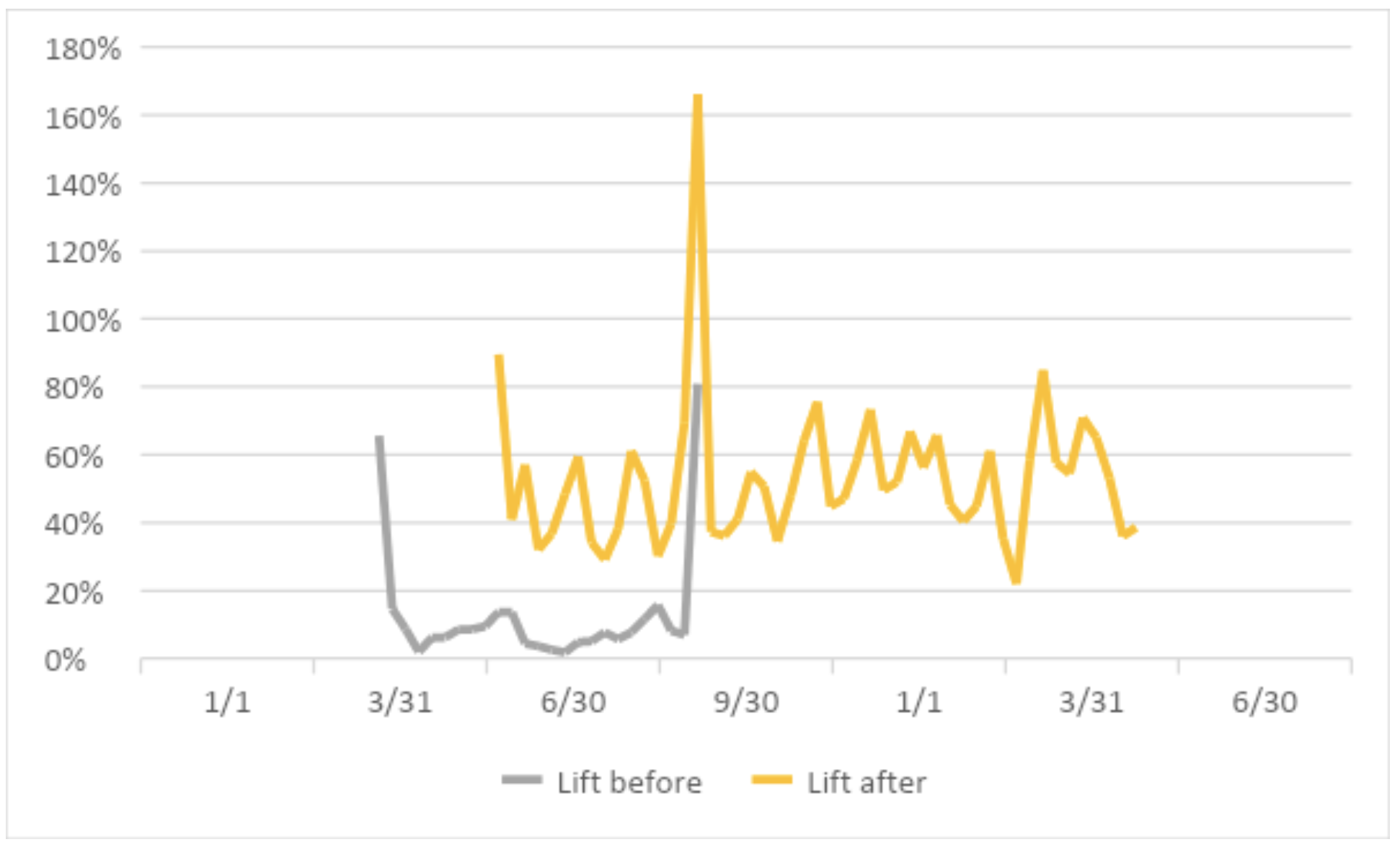

We get a simpler picture by looking at places included in the Eviction Lab’s data that put emergency bans in place in March or April, then lifted them before the CDC order went into effect. The gray line above shows places that had moratoriums in place; they move to the yellow line after they lifted them. At the beginning, in March of 2020, all places are included in the gray line since we are only counting places that had state or local moratoriums. By September 2020, all places are in the yellow line, since we are only counting places that lifted their moratoriums before the CDC’s order went into effect.

Like all places tracked by the Eviction Lab, filings dropped to almost zero in April. But unlike the places that maintained their moratoriums until September, places that lifted them stayed near zero. When they were lifted, these places snapped back to running at a rate of about half the filings of previous years. Except for the spike just before the federal moratorium, they remained at about 50 percent.

Overall, the data suggest state and local eviction bans reduced filings for a few months before the effective ones were lifted and the less effective ones eroded away. We see no obvious effect from the federal ban ordered by Congress, either when it was imposed in March or when it expired in July. The only obvious effect of the CDC moratorium was to encourage a spike in filings right before it was enacted. Afterward, places appeared to continue whatever trends they were on before adoption.

Due to the poor quality of the data, the best we can say is that these are suggestions, but they do accord with common sense. If we accept them, we can try to get a ballpark estimate of the number of eviction filings prevented by these emergency measures during the spring and summer of 2020. From March to early September, when the CDC issued its emergency order, places without state or local moratoriums had 39 percent of the eviction filings expected based on previous years. Places with these temporary bans in effect the entire time had 23 percent. Places that lifted them had 23 percent beforehand and 46 percent afterward.

If we assume in the absence of state and local moratoriums all places would have run at 39 percent of previous years’ filings—the same as places that did not have these temporary measures in place—that comes to 37,623 eviction filings prevented by these emergency orders over the six months.

Of course, an eviction filing often doesn’t lead to an actual eviction, so translating this estimate into the number of evictions that were prevented requires considerable speculation. And we’re missing data for eviction filings in many parts of the country that don’t publicly report their data, do so in an erratic manner, or do so in a way that’s hard to access electronically. Therefore, for each reported filing there are perhaps three times that number. In normal times, evictions may have amounted to about 25 percent of filings, but a survey by The Post and Courier, a South Carolina newspaper, from the summer of 2020 found that the ratio of filings to orders to vacate was under 10 percent during the pandemic. Given the data, state and local eviction bans plausibly might have prevented 10,000 evictions. With all the uncertainties, numbers between zero and 25,000 are plausible, but anyone claiming a far more significant effect has major hurdles explaining that case with the data that we do have, and would need much better data than anyone has produced to date to defend that position.

How many COVID-19 deaths could an eviction plausibly cause? Any single eviction could, in theory, set off a chain causing thousands of deaths. But we know that’s not likely for the average of a large group, since the average number of additional infections caused by an infected person was below two during this period in the U.S., and has dropped below one in 2021. Moreover, bans on eviction for nonpayment of rent also reduce the overall supply of rental housing, particularly for low-income or credit-impaired tenants, increasing cohabitation. Thus, we could reasonably expect that any net effect should be small and negative.

But even if we ignore the offset, 10,000 evictions likely involved tens or hundreds of infected people (infection rates varied from about 0.1 percent to 4 percent in the U.S. at the time depending on location and subpopulation), and double that if we include downstream infected people. Even accounting for rare superspreader events, we could expect no more than a few thousand additional infections in total during the study periods. Using case-mortality ratios from spring and summer 2020, that means around a hundred additional deaths could have been prevented by all the moratoriums.

The data we have on COVID-19 deaths is also problematic—totals offered by serious researchers differ by over 60 percent. But at least we have official processes for recording and counting deaths, unlike evictions.

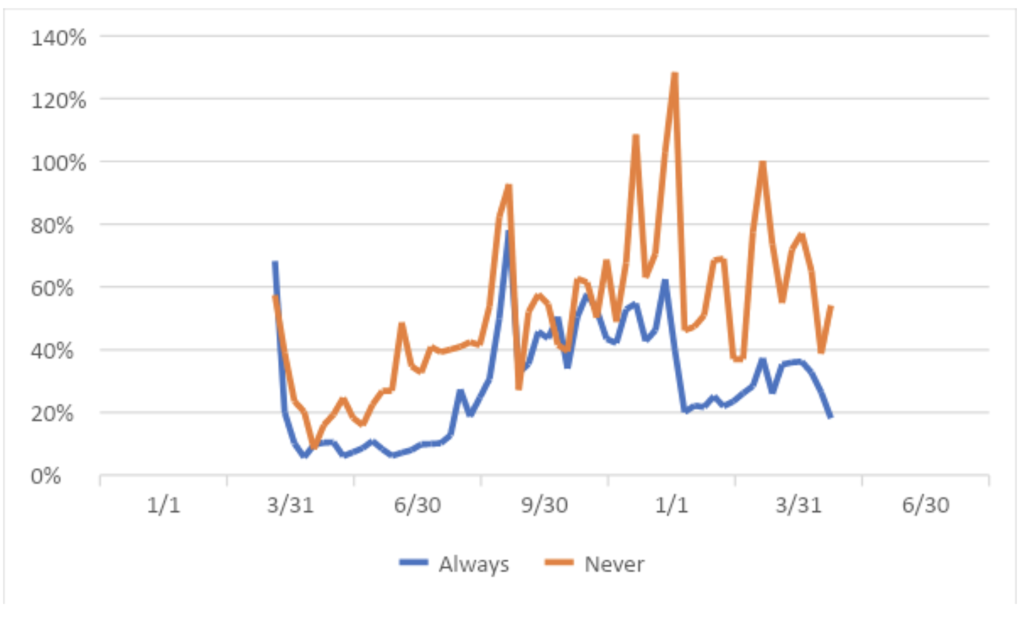

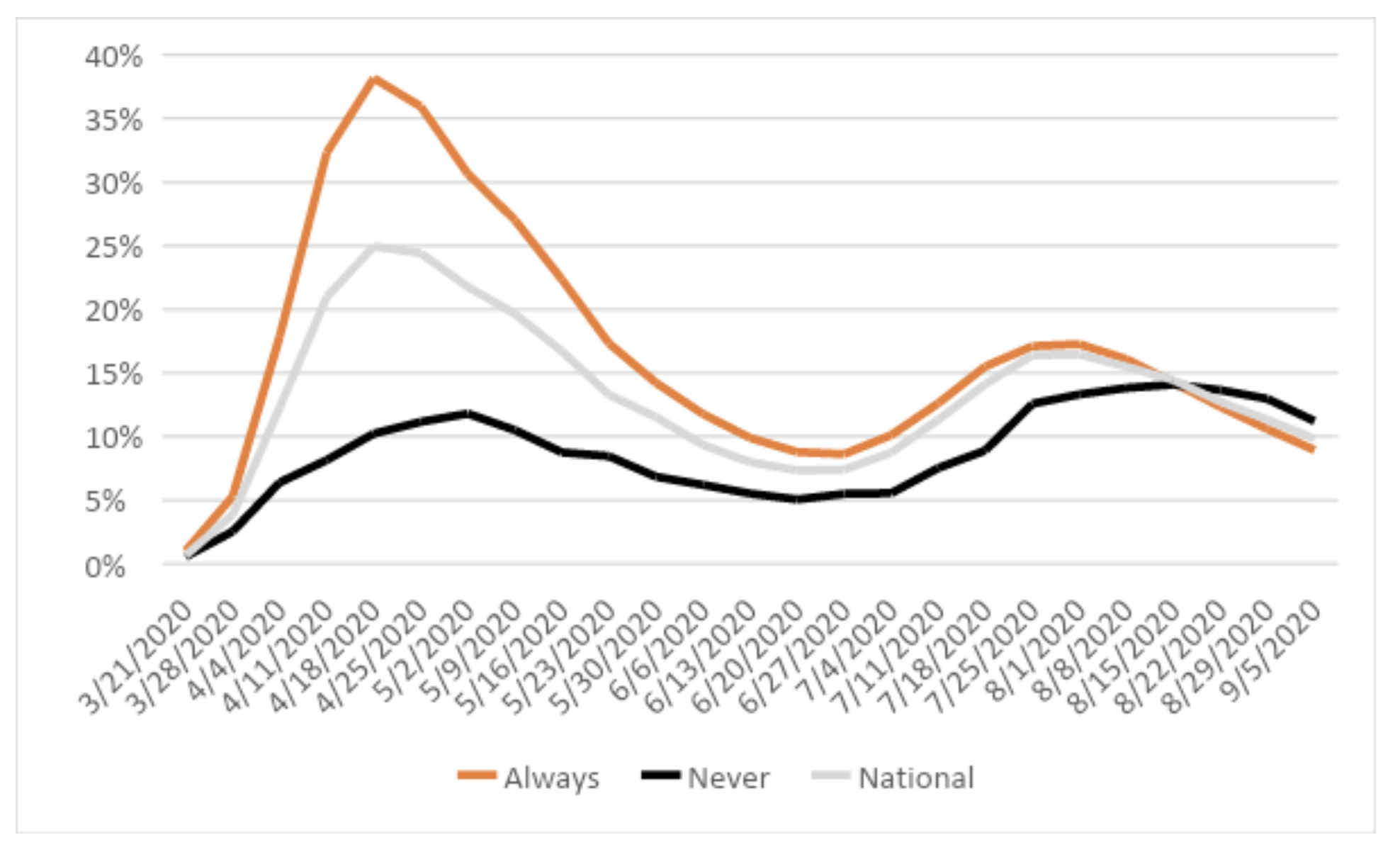

The next graph shows CDC values for COVID-19 deaths as a percentage of the number of deaths expected in the region based on previous years’ data and demographic shifts. The gray line is the U.S. average. You can see that places that implemented eviction moratoriums (the orange line) were hit harder earlier, and had higher rates than places without these temporary measures (the black line) until convergence around mid-August. Of course, it would be absurd to make any causal claims even if the data were reliable—the places that were hit earlier were different in many respects from the places that were hit later.

All the places that were hit hard early put eviction moratoriums in place, so we can’t compare them to other places to see the effects of these policies. But some places with COVID-19 death rates under 5 percent for March and April did enact temporary eviction bans. If we compare these places, we find that among places not hit hard early, COVID-19 death rates were nearly identical through mid-June for places with and without moratoriums, as well as places that had them in place and later lifted them.

However, we expect delays of many weeks between an eviction filing and a COVID-19 death because the eviction process takes time, and it takes more time for it to lead to an infection and death. What the data show is that places with moratoriums—whether or not they were eventually lifted—saw a major increase in COVID-19 deaths, while in places without them, death rates remained low.

How could eviction moratoriums cause increased death rates? One hypothesis is that they could do so by blocking access to rental housing by poor and credit-impaired people—partly by keeping housing stock occupied by nonpaying tenants, but mainly by discouraging landlords from renting. The orders from public health authorities to suspend evictions for nonpayment of rent, including those from the CDC, claim that evictions increase household crowding because evicted people often move in with family or friends, or to crowded public housing or shelters.

But average crowding is the number of renters divided by the number of rental units. An eviction moratorium doesn’t increase the supply of housing. Instead, it causes landlords to remove housing stock from the rental market and, over the long run, discourages new construction and maintenance of existing properties. So while a moratorium might allow some renters to remain in less crowded circumstances, over time it will increase rental crowding. So you shouldn’t expect a significant net public health benefit from preventing an eviction—and in the long run as rental housing for the poor evaporates, the public health effects should be negative.

However, given the poor quality of the data, and the many differences among places unrelated to eviction moratoriums, all we can say is that there’s no evidence that they reduced deaths.

Two Flawed Studies

Now that we have a sense of what the aggregate picture looks like, let’s first examine the study released by a team of public health researchers that the CDC cited in extending the temporary federal ban.

Titled “Expiring Eviction Moratoriums and COVID-19 Incidence and Mortality,” the paper claims 95 percent confidence that excess deaths caused by lifting eviction moratoriums were between 8,988 and 12,470 in the 27 states that ended their bans before the CDC’s order went into effect. Loosely speaking, “95 percent confidence” means the authors claim they are willing to bet $19 against your $1 that if the true number were known, it would be within the range they assert.

How can they claim such precision when people disagree over the number of COVID-19 deaths in these states during this period from 60,000 to 120,000? How can they reconcile this with the data presented above suggesting a limit of 100 or so total COVID-19 deaths resulting from extra evictions nationwide?

The issues are even more glaring when you break the authors’ claims down by state. In most states, lifting eviction restrictions seems to have made little difference. More than half of their national total of extra deaths comes from Texas and South Carolina, where they claim extra deaths amounted to 27 percent of eviction filings, a completely implausible figure. Even if we assume that every filing (not just extra filings from lifting the moratoriums) resulted in an eviction, and every eviction moved infected people into a new residence with 10 existing people (all uninfected and who would not have been infected otherwise), and there was no offset from new people moving into the vacated home, we only get to extra deaths equaling 20 percent of eviction filings.

Another problem is that the authors treat entire states as having no restrictions if there wasn’t a statewide moratorium. But in Texas, several cities and counties had moratoriums before the state imposed its ban and after the state lifted it. In South Carolina, the Supreme Court ordered strong restrictions on orders to vacate when the state ban on eviction filings ended. You can’t blame lifted moratoriums for deaths in places where they were in force. When you adjust for this, there is no evidence that the temporary eviction bans caused a reduction in deaths.

Of course, there could be indirect effects. Maybe evictions make lots of people angry and cause them to go to protests where hundreds of people are infected. Maybe evictions put stress even on non-evicted tenants, making them more susceptible to disease and more likely to engage in risky behavior. But there’s no reason to assume eviction moratoriums reduce these effects—stress and anger are also experienced by people who have trouble finding rental housing, and by landlords losing money on their properties. It’s not eliminated. Moreover, in these cases, temporary eviction bans are contributing factors rather than causes, meaning that there’s no reason to assume they would have the same effects in the future.

Another problem with the study is that these effects would be obvious to people who study evictions and COVID-19. Many housing and legal researchers study evictions, and they would notice if evicted people were all infected with COVID-19 and infected others at six times the population-average rate. All of their subjects and nearly everyone their subjects knew would be sick. COVID-19 researchers would notice that 40 percent of COVID-19 cases and deaths were associated with recent evictions. International researchers would notice that countries with few or no evictions had far lower COVID-19 rates than countries with frequent evictions. And since COVID-19 is hardly the first infectious disease, we’d expect similar effects for other illnesses and thus public health researchers would have spotted the connection long ago.

The researchers also ignore a glaring problem with their analysis: Places with eviction moratoriums during the entire study period had much higher COVID-19 death rates than places without them. The authors simply exclude those places from their study. They only look at places that had restrictions and then lifted them. They don’t compare the death rates in those places to places without restrictions—and we know the places that lifted restrictions have high death rates similar to places with full-time restrictions. They compare each place that lifted their moratoriums to a model of what they think death rates would have been if they had remained in place.

The reason the authors get such tight confidence intervals on their estimates is that they ignore uncertainty in the underlying data, and assume their model fits reality exactly, except for uncorrelated noise. In other words, they ignore all the important factors making it hard to know the effect of moratoriums on health, and report a confidence interval based only on a minor sampling issue.

The authors never try to reconcile their conclusions with actual eviction filings or actual evictions, nor with the experience in the 23 states that either always or never had moratoriums, nor with the experience under federal moratoriums. There’s no attempt at causal reasoning, despite making a causal claim. There’s no discussion of why legal and medical researchers have overlooked such a gigantic effect.

The authors should be commended, however, for complete disclosure of all data and methods. With the second major study on the impact of the eviction moratoriums, the opposite is true; the authors won’t disclose their data or methods.

Nevertheless, we can deduce quite a bit about the errors they committed.

This study, which comes out of Duke University, was co-authored by a team of academics with prestigious credentials, including a professor of economics with a Ph.D. from Stanford University and a quantitative epidemiologist who is an assistant professor of medicine.

In the study, which was published in the National Bureau of Economic Research’s (NBER) working paper series, the authors didn’t include the datasets they had used to reach their conclusions and listed just two of their sources of data. So Reason contacted the authors and asked for access to their data, and posed a series of questions about their sources.

As the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Research Integrity states, “once a researcher has published the results of an experiment, it is generally expected that all the information about that experiment, including the final data, should be freely available for other researchers to check and use.” These guidelines apply to federally funded studies, but are standard practice among academic researchers.

But Duke University denied our request for access to their dataset and the code used to compute their analysis on the grounds that the study hasn’t been peer-reviewed and therefore was “not considered ‘published’ work.” (Although three of the researchers did participate in a podcast, in which one of them reeled off a list of sources that don’t match those cited in the paper. This raises even more concerns about the study’s data.) The Duke paper is what’s known as a “pre-print,” in which researchers make a study publicly available prior to submitting it to an academic journal.

And yet the authors gave interviews in which they promoted their findings, and the paper was widely cited in the press, appears twice in the Federal Register as part of rule-making issued by the CFPB, and was cited in an amicus brief at the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals to support legal arguments that eviction moratoriums have spared COVID-19 deaths.

Duke also trumpeted the findings in a press release that encouraged “members of the media interested in speaking with the authors” to get in touch—though apparently not if that meant scrutinizing the actual dataset or code used to generate the paper’s claims.

In 2019, Duke paid $112.5 million to settle a whistleblower lawsuit that accused the university of protecting a medical researcher found to have used falsified data in 39 academic papers. Following that scandal and others, Duke set up its Office of Scientific Integrity to avoid a repeat scandal. Reason reached out to the office’s assistant dean, Lindsey Spangler, for help in obtaining the dataset used in the Duke study. We also reached out to Associate Vice President for Research and Vice Dean for Scientific Integrity Geeta Swamy. Neither responded to our email requests.

A spokesperson for NBER, the academic journal that published the pre-print, told Reason that it “encourages researchers to make data and code available to other researchers, but it does not require them to” for working papers.

If the findings of the Duke paper on COVID-19 and eviction moratoriums are correct, the authors have made a historic public health discovery—sharing their data and methodology would ensure that the world isn’t deprived of an idea that could save millions of lives.

How did the Duke researchers conclude that eviction moratoriums cause declines in COVID-19 death rates, when we know that states with moratoriums had higher death rates than states without, and that deaths were higher when moratoriums were in force than when they weren’t? The study ignores those two observations and studies only differences among counties within states.

When comparing counties, the study ignores the timing of when restrictions were imposed or lifted and when COVID-19 deaths occurred. The researchers just compare total deaths with the number of days that eviction moratoriums were in force in each county. As a result, it blames deaths on the absence of a moratorium even when a moratorium was in place, or shortly after it was lifted.

Even if we were to ignore all of the other problems with the study and accept that eviction moratoriums help explain differential death rates among counties within states, it would not support the proposition that eviction moratoriums reduce COVID-19 deaths. The study blames all excess deaths on the absence of a moratorium, but the best we would be able to say is that there was a correlation between counties that didn’t have moratoriums in place for a certain period and had excess deaths. Establishing a causal relation, demonstrating that eviction moratoriums reduced deaths from COVID-19, would have to be established at the state level as well, and would have to be consistent with the timing of deaths, particularly to support the high degree of certainty the Duke researchers claim.

The county-level data the researchers used also have all of the problems discussed above, plus enormous new ones. Eviction data are not available at all for one-third of counties, and are erratic for most others. The authors’ claimed source for COVID-19 data (one of the only two sources they mention) is the Atlantic Monthly Group’s COVID Tracking Project, but a project representative told Reason that it does not collect or publish county-level data. Public health data are compiled by public health authorities, whose jurisdictions do not always line up with those of counties. Legal regimes overlap counties—they are affected by federal, state, and local rules, some of which affect multiple counties, and others can affect groups within counties. Most of the data—such as median household income or percentage of the population that is obese—come from surveys, all of which predate the pandemic, and the pandemic changed those numbers a lot.

Moreover, the study’s analysis relies on county-level data, the largest survey of which has 60,000 households, meaning an average of 20 per county, with many counties not represented at all. Only with heroic guesswork and approximation can the data be lined up properly, and of course, the data have big problems in the first place.

Despite these obstacles, the authors are 95 percent confident that universal moratoriums could have reduced COVID-19 death rates by 40.7 percent compared to a hypothetical scenario with no moratoriums at all—apparently plus or minus about 5 percent, although readers are left to guess the range from a graph. This is a stunning assertion. It is impossible statistically to derive such precise estimates from such uncertain data.

Doing our best to replicate what we think the authors did, we find no significant relation at all, much less anything of the size and certainty the authors claim. Even if the authors’ results are correct regarding the differences among counties within a state, since they are inconsistent with differences among states, they cannot be used to predict the effects of nationwide adoption.

These two deeply flawed studies are worthy of intense scrutiny because of their influence on public policy. They provided justification for a series of temporary measures that have had an impact on the livelihoods of landlords all over the country by denying them the legal recourse to enforce their contracts. And although the moratoriums will eventually expire, activists with the “cancel rent” movement, who see the landlord-tenant relationship as inherently “exploitative,” hope to use the pandemic as an opportunity to make progress in their goal of stripping away the power of landlords to evict tenants altogether, which would eviscerate the private rental market.

To the extent we are going to involve scientific researchers in policy discussions, we should concentrate on issues that have been studied by many people who are openly sharing data and arguing back and forth until there is a consensus among experts. These shoddy one-off studies are just ammunition for people who want to put a link saying “studies prove” in their otherwise completely speculative articles.

Produced and edited by Justin Monticello. Written by Monticello and Aaron Brown. Graphics by Isaac Reese. Audio production by Ian Keyser.

Music: Aerial Cliff by Michele Nobler, Land of the Lion by C.K. Martin, The Plan’s Working by Cooper Cannell, Thoughts by ANBR, Flight of the Inner Bird by Sivan Talmor and Yehezkel Raz, and Run by Tristan Barton.

Photos: Marilyn Humphries/Newscom; John Rudoff/Sipa USA/Newscom; Erik McGregor/Sipa USA/Newscom; Marilyn Humphries/Newscom; John Rudoff/Sipa USA/Newscom; Erik McGregor/Sipa USA/Newscom; Erik McGregor/Sipa USA/Newscom; Erik McGregor/Sipa USA/Newscom

Eviction protest footage: Liberation News/YouTube

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3jw5RO3

via IFTTT